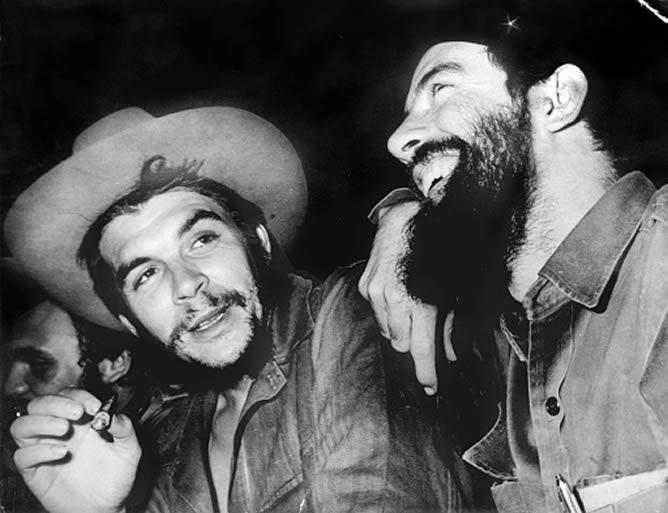

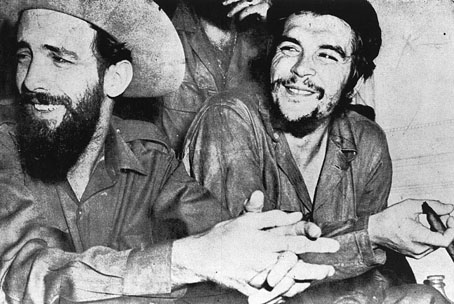

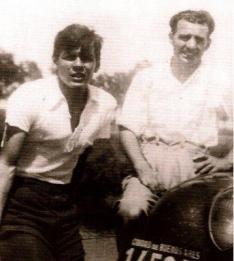

Ο Τσε με τον σύντροφο και φίλο Κομαντάντε Καμίλο Σιενφουέγος, εκ των πρωτεργατών της Κουβανικής Επανάστασης.

Ελληνικό Αρχείο Τσε Γκεβάρα © Guevaristas

Η πρώτη και πληρέστερη ελληνική ιστοσελίδα για τον Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα.

Ο Τσε με τον σύντροφο και φίλο Κομαντάντε Καμίλο Σιενφουέγος, εκ των πρωτεργατών της Κουβανικής Επανάστασης.

Κριτική στο βιβλίο: Che Guevara. His Revolutionary Legacy, των Olivier Besancenot και Michael Lowy. Monthly Review Press, 2009.

Κριτική στο βιβλίο: Che Guevara. His Revolutionary Legacy, των Olivier Besancenot και Michael Lowy. Monthly Review Press, 2009.

Της Κιτ Άνταμ Γουάινερ.

Το ότι η μορφή του Τσε Γκεβάρα βρίσκεται σε τοίχους και t-shirts σε όλον τον κόσμο δεν αποτελεί νέο. Στη Λατινική Αμερική, τις δεκαετίες του 1970 και ’80, ένας ταξιδιώτης μπορούσε να δει το πρόσωπο του Τσε ζωγραφισμένο με σπρέι σε τοίχους εργατικών συνοικιών. Στην επαναστατική Νικαράγουα το γκραφίτι με τη μορφή του Τσε απαγορεύτηκε επισήμως, όπως συνέβη με το τεράστιο κύμα «της τέχνης των τοίχων» υπέρ των Σαντινίστας και κατά των Κοντρας. Ως μάρτυρας ο Τσε συμβολίζει την προσήλωση και την ελπίδα για αντι-ιμπεριαλιστικές ομάδες ανταρτών σε όλην την Αμερική.

Τι είναι καινούργιο σήμερα στην εμπορικότητα της εικόνας του Τσε. Ο Τσε είναι υπερεκτεθιμένος σε ρουχισμό, μπιχλιμπίδια, ρολόγια. Εμφανίζεται σε γυμνάσια, κολλέγια και στους δρόμους του lower Μανχάταν. Για κάποιους η ατίθαση γενιάδα και ο μαύρος μπερές έχουν αναμφίβολα μια αισθητική αξία. Συμβολίζει ο Τσε την αντίσταση, την αντι-εξουσιαστική διάθεση ή κάποια προσωπική στάση που μόνο οι θαυμαστές του αντιλαμβάνονται;

Το βιβλίο των Ολιβιέρ Μπεσανσενό και Μάικλ Λεβί ‘Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Legacy’ αποτελεί μια ευπρόσδεκτη προσπάθεια να προχωρήσει ένα βήμα παραπέρα από τη «μόδα του Τσε» και να επανακαθορίσει το παρελθόν – μια επαναστατική σοσιαλιστική κληρονομιά βασισμένη στη ζωή και στις ιδέες του Τσε Γκεβάρα. Οι συγγραφείς είναι, αντίστοιχα, ένας γάλλος συνδικαλιστής και προεδρικός υποψήφιος της επαναστατικής αριστεράς (Μπεσανσενό) και ένας κορυφαίος θεωρητικός του μαρξισμού, συγγραφέας πάνω σε επαναστατικές παραδόσεις της Ευρώπης και της Λατινικής Αμερικής (Λεβί).

Για τους συγγραφείς «κλειδί» για την κατανόηση της κληρονομιάς του Τσε είναι η εκτίμηση του αντι-Σταλινισμού του. Ο Μπεσανσενό και ο Λεβί ανιχνεύουν τα χρόνια της πολιτικής συνειδητοποίησης του Τσε στη Γουατεμάλα του ρεφορμιστή Γιακόμπο Άρμπενς. Ο Τσε έγινε αυτόπτης μάρτυρας της αδυναμίας του ρεφορμιστικού προγράμματος να αντιμετωπίσει το ιμπεριαλιστικό πραξικόπημα του 1954 και, ως εκ τούτου, μετακινήθηκε ριζοσπαστικά προς την αριστερά. Αποσχίστηκε από τη «διεπίπεδη» ορθοδοξία των κομμουνιστικών κομμάτων – ένα σχήμα που υποστήριζε ένα μεταβατικό στάδιο «μπουζουαρζικής δημοκρατικής» ανάπτυξης ως προάγγελο της σοσιαλιστικής φάσης. Οι θεωρητικοί του κομμουνισμού προέτρεπαν το «ποίμνιο» τους να συγκρατούν τις επαναστατικές τους ορμές κατά το «δημοκρατικό στάδιο», να περιορίζουν την δραστηριότητα της εργατικής τάξης στον Τρίτο Κόσμο χάρην συμμαχιών με «εθνικές αστικές τάξεις» για τη δημιουργία δημοκρατικών, αντι-ιμπεριαλιστικών μπλοκ. Οι συνέπειες ήταν τραγικές. Η δημοκρατική κυβέρνηση της Γουατεμάλα θα ανατρέπονταν από ένα, στηριζόμενο από τις ΗΠΑ, πραξικόπημα το 1954. Παρομοίως, ένα στρατιωτικό πραξικόπημα θα διέλυε τη σοσιαλιστική κυβέρνηση του Σαλβαδόρ Αλιέντε στη Χιλή, στις 11 Σεπτέμβρη του 1973. Και στις δύο περιπτώσεις οι κομμουνιστές θα φυλακίζονταν η θα δολοφονούνταν εν ψυχρώ.

Παρ’ όλα αυτά υπήρχε μια λογική στη στρατηγική αυτή. Η συγκράτηση (απραξία) των κομμουνιστών «έδενε» με την σοβιετική εξωτερική πολιτική η οποία νοιάζοταν λιγότερο γιά την προώθηση επαναστάσεων στον κόσμο και περισσότερο με τη δημιουργία συμμαχιών στο πλαίσιο του Ψυχρού Πολέμου. Πρώτα και πάνω απ’ όλα, η Μόσχα επιθυμούσε τη διατήρηση ενός status quo ισορροπίας μεταξύ των αντίπαλων στρατοπέδων, ώστε να μην επιχειρούσαν επίθεση κατά της Σοβιετικής Ένωσης οι ιμπεριαλιστικές χώρες. Σε αυτό το πλαίσιο, η δημιουργία συμμαχιών με εθνικές καπιταλιστικές τάξεις που αποζητούσαν μια κάποια αυτονομία από την Ουάσινγκτον φαίνονταν λογική για την πολιτική των μεγάλων δυνάμεων. Παρ’ όλα αυτά, δεν είχε ουδεμία σχέση με την επανάσταση. Και σύμφωνα με τους Μπεσανσενό και Λεβί, ο Τσε το αντιλήφθηκε αυτό τη δεκαετία του 1950.

Συνοψίζοντας τα μαθήματα από την εμπειρία της Γουατεμάλα, ο Τσε κατέληξε σε μια άποψη παρόμοια με αυτήν που ο Λένιν είχε αναπτύξει στις «Θέσεις του Απρίλη» το 1917. Για τους Μπεσανσενό και Λεβί, με την απόρριψη της αντίληψης περί «επιπέδων» της δημοκρατικής μεταβατικής περιόδου ο Τσε αποσυνδέονταν από το όλο Σοβιετικό μοντέλο και αυτοτοποθετούνταν ολοκληρωτικά στο στρατόπεδο της αντι-σταλινικής επαναστατικής αριστεράς. Εξυπακούεται ότι ο επανακαθορισμός και η επανασύσταση της πραγματικής (πολιτικής) κληρονομιάς του Τσε ενδέχεται να έχει μεγάλο αντίκτυπο στην επαναθεμελίωση μιάς επαναστατικής αριστεράς στη Λατινική Αμερική. Όπως αναφέρουν, μάλλον ποιητικά, οι συγγραφείς, «πολλοί ισχυρίζονται ότι η φλόγα της ελπίδας μας έσβησε με την κατάρρευση της τραγικής και αιματηρής εμπειρίας γνωστής ως ‘υπαρκτός σοσιαλισμός’. Απαντούμε: ένα καντήλι ακόμη καίει – ο κομμουνισμός του Τσε Γκεβάρα».

Τα πολλαπλά πρόσωπα του Σταλινισμού

Ο Μπεσανσενό και ο Λεβί προσεγγίζουν το θέμα τους με μεγάλη φιλολογική ικανότητα και μια μοναδική αφοσίωση στην επανεκίνηση του επαναστατικού κινήματος στην Αμερική και διεθνώς. Είναι αποφασισμένοι να χρησιμοποιήσουν τα καλύτερα στοιχεία της κληρονομιάς του Τσε προκειμένου να πετύχουν αυτόν τον στόχο. Αυτή τους η αφοσίωση, παρ’ όλα αυτά, τους οδηγεί στην υποτίμηση της απόρριψης, εκ μέρους του Τσε, της δημοκρατίας ως αντίδοτο του «γραφειοκρατικού μαρξισμού» και στην αγνόηση αποδεικτικών στοιχείων που έρχονται σε αντίθεση με τον χαρακτηρισμό του Τσε ως αντιπάλου του Σταλινισμού. Η προσήλωση του Τσε στις ιδέες και τις πολιτικές του Στάλιν, αλλά και η τιμή προς το ίδιο το πρόσωπο του σοβιετικού ηγέτη, αποδεικνύεται ευρέως στο γραπτό έργο του Σαμ Φαρμπερ. Μια απόσχιση από το σοβιετικό μοντέλο της «σοσιαλιστικής» μετάβασης και ανάπτυξης δεν ισοδυναμεί με αντι-σταλινισμό. Αντιθέτως, αυτό που απέρριψε ο Τσε ήταν η περίοδος του «λαϊκού μετώπου» του σταλινισμού – το απέρριψε όμως χάρην ενός είδους υπερεθελοντισμού που είχε απομείνει από την «Τρίτη περίοδο» (1928-1934) του σταλινισμού, με τις ακραίες και καταστροφικές πολιτικές συλλογικοποίησης και τις ψεύτικες υποσχέσεις της επερχόμενης παγκόσμιας επανάστασης. Στην πραγματικότητα, τη δεκαετία του 1960 όταν η (ιδεολογική) απόσχιση του Τσε από τη Μόσχα δημοσιοποιήθηκε, ο σταλινικού τύπου κομμουνισμός δεν ήταν πλέον μονολιθικός. Μεταξύ των ηγετών του ήταν υπερασπιστές του επαναστατικού αγώνα, του δημοκρατικού ρεφορμισμού, αποσχισμένες φατρίες της Μόσχας και ακόμη η απόρροψη της κληρονομιάς του ίδιου του Στάλιν. Ο Μάο Τσε Τούνγκ και ο Χο Τσι Μινχ, για παράδειγμα, ηγήθηκαν αμφότεροι επαναστατικών κινημάτων τα οποία ανέτρεψαν φιλοιμπεριαλιστικά καθεστώτα και διέκοψαν τα σοβιετικά σχέδια για μεταπολεμική σταθερότητα. Η απόσχιση του Μάο από την ΕΣΣΔ πήρε δημόσιες διαστάσεις το 1960, οδηγώντας σε διαιρέσεις μεταξύ των κομμουνιστικών κομμάτων ανα τον κόσμο. Ο Μάο απέρριψε τον μη-επαναστατικό δρόμο της Μόσχας προς το σοσιαλισμό και, κατά την πολιτιστική επανάσταση, κύρηξε πόλεμο στον «γραφειοκρατισμό». Παρ’ όλα αυτά, ο Μάο ήταν ένας καθαρός σταλινιστής, οι ακρατικές καμπάνιες είχαν πτωτική πορεία και ποτέ δεν βασίστηκαν στην αυτό-οργάνωση των κινέζων εργατών. Και οι εξωτερικές του πολιτικές απεδείχθησαν όχι λιγότερο τυχοδιωκτικές από αυτές της Μόσχας. Το σχίσμα του 1948 μεταξύ των Τίτο και Στάλιν οδήγησε στην επιβίωση ενός κομμουνιστικού κράτους (σ.σ. Γιουγκοσλαβία) που απέρριπτε ανοιχτά την σταλινική κληρονομιά και τον ίδιο τον Στάλιν προσωπικά. Κατά ειρωνεία, τα μέσα που το κομμουνιστικό κόμμα της Γιουγκοσλαβίας χρησιμοποίησε προκειμένου να καταπιέσει τους γιουγκοσλάβους σταλινιστές των αρχών του ’50 περιελάμβαναν μυστική αστυνομία και δίκες αμφιβόλου αμεροληψίας.

Μεταξυ των γιουγκοσλάβων κομμουνιστών ηγετών ήταν διανοούμενοι οι οποίοι έκαναν φιλότιμες προσπάθειες να μελετήσουν τα προβλήματα της γραφειοκρατείας, την ανάγκη αποκεντροποίησης και την παραγωγή ποιοτικών καταναλωτικών αγαθών. Στα 1950 και 1960 αυτοί οι κομμουνιστές προέβαλαν το ζήτημα του ελέγχου των εργατών στο πλαίσιο του σοσιαλισμού και σχεδίασαν ένα σύστημα αυτό-οργάνωσης των ίδιων των εργατών. Παρ’ όλα αυτά, η αυτό-οργάνωση των εργατών ήταν γενικά ουτοπική. Οι εργάτες ποτέ δεν ήλεγχαν τον κεντρικό σχεδιασμό και δεν ήταν ποτέ σε θέση να αποφασίσουν πως θα έπρεπε να ρυθμιστεί ο γιουγκοσλαβικός σοσιαλισμός σε μακρο-οικονομικό επίπεδο. Την στιγμή που η Γιουγκοσλαβία παρέμεινε λιγότερο καταπιεστική σε σχέση με τις άλλες ανατολικοευρωπαϊκές χώρες, το ΚΚ της Γιουγκοσλαβίας δεν απεμπόλησε ποτέ το κεντρικό δόγμα του μονοκομματικού κράτους στο οποίο η εξουσία και τα προνόμοια της ηγεσίας του βασίζονταν στην αστυνομική δύναμη. Στην ίδια τη Συμφωνία της Βαρσοβίας αναδείχθησαν αρκετοί κομμουνιστές ηγέτες που αμφισβήτησαν την σταλινική ορθοδοξία. Στο πλαίσιο της «Αποσταλινοποίησης» του Νικίτα Χρουτσώφ και ωθούμενοι από κινήματα, εργάτες και διανοουμένους, οι Βλάντισλαβ Γκομούλκα (Πολωνία 1956), Ιμρέ Ναγί (Ουγγαρία 1956) και Αλεξάντερ Ντουμπτσεκ (Τσεχοσλοβακία 1968) αναδείχθηκαν μέσα από διαδικασίες σταλινικών κομμουνιστικών κομμάτων και αποκύρηξαν τον Σταλινισμό. Την στιγμή που ο αντι-σταλινισμός του Γκομούλκα ήταν πάντοτε σχεδιασμένος ώστε να διατηρεί το μονοκομματικό καθεστώς την ώρα που ευαγγελίζονταν μια ριζοσπαστικοποιημένη εργατική τάξη, οι Ναγί και Ντουμπτσεκ έδειχναν να πιστεύουν πως μπορούσαν να χτίσουν έναν πιο ανθρώπινο σοσιαλισμό στο πλαίσιο της κυριαρχίας του κομμουνιστικού κόμματος. Παρ’ όλα αυτά, κανένας τους δεν ήταν διατεθειμένος να αποσχιστεί από τα κομμουνιστικά κόμματα τους η να προσπαθήσει να δημιουργήσει αντιπολιτευόμενα εργατικά κόμματα. Και κανείς δεν ανέπτυξε σχεδιασμούς ικανούς να αντισταθούν στην σοβιετική ισχύ.

Είναι άξιο θαυμασμού ότι οι Μπεσανσενό και Λεβί επιχειρούν να χρησιμοποιήσουν τις πλέον επαναστατικές ιδέες του Τσε προκειμένου να «παρέμβουν» στη διαδικασία δημιουργίας μιας νέας αριστεράς στη Λατινική Αμερική. Ακόμη, η πρόσφατη αναβίωση αυτής της αριστεράς έρχεται σε μια περίοδο όπου τα ζητήματα της γραφειοκρατίας και του εργατικού ελέγχου συνεχίζουν να είναι πιεστικά και η κυρίαρχη άποψη μιας σοσιαλιστικής μετάβασης κινείται γύρω από ισχυρούς ηγέτες. Και το κομμουνιστικό κόμμα του Τσε συνεχίζει να κυβερνά την Κούβα. Ως εκ τούτου μια πιο κριτική ματιά στον αντι-σταλινισμό του Τσε είναι αναγκαία, λαμβάνοντας υπ’ όψη το ότι η πολιτική του κληρονομιά υιοθετείται από ποικιλλία συλλογικοτήτων όπως το κουβανικό κομμουνιστικό κόμμα, το ενωμένο σοσιαλιστικό κόμμα του Ούγκο Τσάβες και το EZLN των Ζαπατίστας στο νότιο Μεξικό. Η διαφορά μεταξύ του επαναστάτη Τσε και του φιλο-σταλινικού Τσε εμφανίζεται στο πρώτο κεφάλαιο, «Ένας μαρξιστικός ανθρωπισμός». Ο Μπεσανσενό και ο Λόουι κάνουν έκκληση για έναν σοσιαλισμό βασισμένο σε ανθρωπιστικές αρχές, θέτοντας ως προτεραιότητα το μετασχηματισμό των ανθρώπων σε ηθικά όντα απελευθερωμένα από το (καπιταλιστικό) νόμο της αξίας. Παραπέμπουν σε πολλά από τα γραπτά του Τσε προκειμένου να προβάλλουν την άποψη του ότι η επαναστατική διαδικασία μεταβάλλει τον ατομικιστή άνθρωπο σε «κολλεκτιβιστική» μονάδα ταγμένη στην σοσιαλιστική αλληλεγγύη. Θα έπρεπε όμως να αντιμετωπίσουμε τα όρια που έθεσε ο Τσε: Τι εννοούμε όταν μιλάμε για ανθρωπισμό σε μια μετα-επαναστατική κοινωνία; Πιο συγκεκριμένα – τι είναι ο ανθρωπισμός χωρίς δημοκρατία;

Όπως αναφέρει ο Σαμ Φαρμπερ, το αντίδοτο του Τσε στον ατομισμό και την απομόνωση της εργατικής τάξης ήταν ένας καθολικός εθελοντισμός μέσα από τον οποίο οι εργάτες καλούνταν να θυσιαστούν για το ευρύτερο σοσιαλιστικό καλό, όχι για τον εργατικό έλεγχο. Ήρθε αντιμέτωπος με προσπάθειες κουβανών εργατών να διατηρήσουν ανεξάρτητες ενώσεις και έπαιξε σημαίνοντα ρόλο στο «χτίσιμο» του μονοκομματικού κράτους.

Ο Μπεσανσενό και ο Λεβί ασκούν κριτική στον Τσε για την άρνηση του να αναγνωρίσει την εργατική δημοκρατία ως αντίδοτο στην γραφειοκρατία (54-57) όσο και για την υποστήριξη που παρείχε στη θανατική ποινή. Ασκούν κριτική όμως περιληπτικά και σύντομα χωρίς να εξετάζουν τις αντιφάσεις μεταξύ του ουμανισμού του Τσε και του ρόλου του στη δημιουργία μιάς κοινωνίας στην οποία οι εργάτες έχουν μικρό ρόλο στον καθορισμό του τι παράγουν, πόσο παράγουν και στην οποία παραμένουν απομονωμένοι.

Βρισκόμαστε ακόμη στην πρώϊμη φάση της επανασυγκρότησης μιάς αριστεράς που είναι και επαναστατικά σοσιαλιστική και δημοκρατική. Είναι αναπόφευκτο ότι οι επαναστάτες θα ανακαλύψουν ξανά παλαιούς στοχαστές και πρόσωπα χωρίς αναγκαστικά να υιοθετήσουν το σύνολο των απόψεων τους. Είναι όμως ουσιαστικό μαθαίνοντας από το παρελθόν να είμαστε, εν τέλει, τόσο κριτικοί όσο και θαυμαστές. Ο Τσε Γκεβάρα είχε θαυμαστές αρετές αλλά η υποστήριξη του προς έναν σοσιαλισμό που δεν περιελάμβανε την εργατική δημοκρατία συνέβαλε στις αποτυχίες της παλιάς αριστεράς και είναι ένας απ’ τους λόγους που η προσπάθεια που κάνουμε τώρα είναι αυτή της Επαναθεμελίωσης (της αριστεράς).

ATC 143, Νοέμβριος – Δεκέμβριος 2009.

(Το άρθρο δημοσιεύθηκε στην ιστοσελίδα της αμερικανικής σοσιαλιστικής ένωσης «Solidarity»).

«We shall reply to this by quoting two lines from a Russian fable, ‘Eagles may at times fly lower than hens but hens can never rise to the height of eagles’. [Rosa ] in spite of her mistakes […] was and remains for us an eagle. And not only will Communists all over the world cherish her memory, but her biography and her complete works will serve as useful manuals for training many generations of communists all over the world. ‘Since August 4, 1914, German social-democracy has become a stinking corpse’ ‑ this statement will make Rosa Luxemburg’s name famous in the history of the international working class movement. And, of course, in the backyard of the working class movement, among the dung heaps, hens like Paul Levi, Scheidemann, Kautsky and all their fraternity will cackle over the mistakes committed by the great Communist». (Lenin Collected Works, Vol. 33, p. 210, Notes of a Publicist, Vol. 33).

«When I began to study medicine most of the concepts I now have as a revolutionary were then absent from my warehouse of ideals. I wanted to be successful, as everyone does. I used to dream of being a famous researcher, of working tirelessly to achieve something that could, decidedly, be placed at the service of mankind, but which was at that time all about personal triumph. I was, as we all are, a product of my environment.»

«Although we’re too insignificant to be spokesmen for such a noble cause, we believe, and this journey has only served to confirm this belief, that the division of America into unstable and illusory nations is a complete fiction. We are one single mestizo race with remarkable ethnographical similarities, from Mexico down to the Magellan Straits. And so, in an attempt to break free from all narrow-minded provincialism, I propose a toast to Peru and to a United America.»(Motorcycle Diaries, p.135).

«Perhaps this was the first time I was confronted with the real-life dilemma of having to choose between my devotion to medicine and my duty as a revolutionary soldier. Lying at my feet were a knapsack full of medicine and a box of ammunition. They were too heavy for me to carry both of them. I grabbed the box of ammunition, leaving the medicine behind « (Quizás esa fue la primera vez que tuve planteado prácticamente ante mí el dilema de mi dedicación a la medicina o a mi deber de soldado revolucionario. Tenía delante de mí una mochila llena de medicamentos y una caja de balas, las dos eran mucho peso para transportarlas juntas; tomé la caja de balas, dejando la mochila ….»)

«We established our defensive line on the Cautillo River. We had Mapos surrounded, but there was still Palma. There were approximately 300 enemy soldiers. We had to take Palma. We were also anxious to take the arms that were to be found in Palma, because when we left La Plata, in the Sierra Maestra, because of the latest offensive, we left with 25 armed soldiers and 1,000 unarmed recruits. We armed those troops along the way. We armed them during the fighting, but we really finished fully arming them in Palma.»

«The Commune was formed of the municipal councillors, chosen by universal suffrage in the various wards of the town, responsible and revocable at short terms. The majority of its members was naturally working men, or acknowledged representatives of the working class. The Commune was to be a working, not a parliamentary body, executive and legislative at the same time.

«Instead of continuing to be the agent of the Central Government, the police was at once stripped of its political attributes, and turned into the responsible, and at all times revocable, agent of the Commune. So were the officials of all other branches of the administration. From the members of the Commune downwards, the public service had to be done at workman’s wage. The vested interests and the representation allowances of the high dignitaries of state disappeared along with the high dignitaries themselves. Public functions ceased to be the private property of the tools of the Central Government. Not only municipal administration, but the whole initiative hitherto exercised by the state was laid into the hands of the Commune.

«Having once got rid of the standing army and the police – the physical force elements of the old government – the Commune was anxious to break the spiritual force of repression, the «parson-power», by the disestablishment and disendowment of all churches as proprietary bodies. The priests were sent back to the recesses of private life, there to feed upon the alms of the faithful in imitation of their predecessors, the apostles.» (Marx, The Civil War in France, The Third Address, May, 1871 [The Paris Commune])

«We shall reduce the role of state officials,» wrote Lenin, «to that of simply carrying out our instructions as responsible, revocable, modest paid ‘foremen and accountants’ (of course, with the aid of technicians of all sorts, types and degrees). This is our proletarian task, this is what we can and must start with in accomplishing the proletarian revolution.» (LCW, Vol. 25, p. 431.).

«In this long period of holidays [sic!] I have stuck my nose into philosophy, which is something I have been meaning to do for a long time. I met my first difficulties in Cuba [where] there is nothing published except the unreadable Soviet tomes [literally «Soviet bricks» los ladrillos soviéticos] which have the drawback that they do not allow you to think, since the Party has done it for you and you just have to swallow it. As a method, this is completely anti-Marxist, and furthermore they are mostly very bad.»

«If you take a look at the publications [in Cuba] you will see a profusion of Soviet and French authors [He is referring to the French hard-line Stalinists like Garaudy]. This is due to the ease with which translations are obtained and also to ideological tail-endism [seguidismo ideológico]. This is not the way to give Marxist culture to the people. In the best case it is Marxist propaganda [divulgación marxista], which is necessary, if it is of good quality (which is not the case), but insufficient.»

«Προσπαθούσαμε να έρθουμε σε απευθείας επαφή με τους γιατρούς του Πετροουέ, αλλά αυτοί μόλις γύριζαν από τις δραστηριότητες τους και, μην έχοντας καιρό για χάσιμο, δε μας παραχωρούσαν ούτε μία τυπική συνάντηση-ωστόσο τους είχαμε εντοπίσει και εκείνο το απόγευμα χωριστήκαμε: ο Αλμπέρτο τους ακολούθησε και εγώ πήγα να δω μια ασθματική γερόντισσα, πελάτισσα της «Τζοκόντα». Τη λυπόσουν την καψερή, το δωμάτιο της βρομούσε ιδρωτίλα, ποδαρίλα και σκόνη από δυο τρεις πολυθρόνες, τα μοναδικά είδη πολυτελείας στο σπίτι της. Εκτός από το άσθμα, υπέφερε και από καρδιακή ανεπάρκεια. Ήταν μία από τις περιπτώσεις που ένας γιατρός, συνειδητοποιώντας ότι είναι ανίσχυρος μπροστά στην κατάσταση, νιώθει την επιθυμία μιας ριζικής αλλαγής, που να εξαλείψει την αδικία η οποία ανάγκασε τη γριά γυναίκα να δουλεύει σαν υπηρέτρια μέχρι τον προηγούμενο μήνα για να βγάλει το ψωμί της, ασθμαίνοντας, υποφέροντας, μα κρατώντας ψηλά το κεφάλι στη ζωή. Το ζήτημα είναι πως στις φτωχές οικογένειες το μέλος που αδυνατεί να κερδίσει τα προς το ζην περιβάλλεται από μια ατμόσφαιρα δυσαρέσκειας, που κρύβεται με το ζόρι. Από εκείνη τη στιγμή παύει να είναι πατέρας, μητέρα, αδερφός· γίνεται ένας αρνητικός παράγοντας στον αγώνα για επιβίωση και, ως τέτοιος, στόχος μνησικακίας της υγιούς κοινότητας, που θεωρεί την αναπηρία του σαν προσωπική προσβολή γι’ αυτούς που πρέπει να τον συντηρήσουν. Εκεί, στις τελευταίες ώρες για τους ανθρώπους των οποίων ο ορίζοντας δεν εκτείνεται πέρα από το αύριο, εκεί επικεντρώνεται η τραγωδία της ζωής του προλεταριάτου όλου του κόσμου. Στα μάτια των ετοιμοθάνατων βλέπεις μια καρτερική έκκληση συγνώμης και, συχνά, μια απελπισμένη έκκληση παρηγοριάς που χάνεται στο κενό, όπως θα χαθεί γρήγορα και το σώμα μέσα στην απεραντοσύνη του μυστηρίου που μας περιβάλλει. Ως πότε θα συνεχιστεί αυτή η τάξη πραγμάτων που βασίζεται σε μια παράλογη διαίρεση, στις κοινωνικές τάξεις; Είναι κάτι στο οποίο δεν μπορώ να απαντήσω εγώ, αλλά είναι καιρός οι κυβερνώντες να αφιερώσουν λιγότερο χρόνο στην προπαγάνδα της ποιότητας των καθεστώτων τους και περισσότερα χρήματα, πολύ περισσότερα, για έργα κοινωνικής ωφέλειας. Δεν μπορώ να κάνω πολλά για την άρρωστη· της γράφω απλώς μια κατάλληλη δίαιτα, ένα διουρητικό και αντιασθματικά διαλύματα. Μου έχουν μείνει μερικές δραμαμίνες και της τις χαρίζω. Όταν βγαίνω, με ακολουθούν τα στοργικά λόγια της γερόντισσας και οι αδιάφορες ματιές των συγγενών».

[Το χαμόγελο της «Τζοκόντα», Ημερολόγια Μοτοσικλέτας].

Thus, I remember that during the days of Batista’s final offensive in the Sierra Maestra mountains against our militant but small forces, the most experienced cadres were not in the front lines; they were assigned strategic leadership assignments and save for our devastating counterattack. It would have been pointless to put Che, Camilo [Cienfuegos], and other compañeros who had participated in many battles at the head of a squad. We held them back so that they could subsequently lead columns that would undertake risky missions of great importance, it was then that we did send them in enemy territory with full responsibility and awareness of the risks as in the case of the invasion of Las Villas led by Camilo and Che, an extraordinarily difficult assignment that required men of great experience and authority as column commanders, men capable of reaching the goal.

Thus, I remember that during the days of Batista’s final offensive in the Sierra Maestra mountains against our militant but small forces, the most experienced cadres were not in the front lines; they were assigned strategic leadership assignments and save for our devastating counterattack. It would have been pointless to put Che, Camilo [Cienfuegos], and other compañeros who had participated in many battles at the head of a squad. We held them back so that they could subsequently lead columns that would undertake risky missions of great importance, it was then that we did send them in enemy territory with full responsibility and awareness of the risks as in the case of the invasion of Las Villas led by Camilo and Che, an extraordinarily difficult assignment that required men of great experience and authority as column commanders, men capable of reaching the goal. Του Πάνου Τριγάζη.

Του Πάνου Τριγάζη.