Συντάκτης: Guevaristas

Συνέντευξη του Καμίλο Γκεβάρα στο «Ριζοσπάστη» (2006)

Συνέντευξη στο Δημήτρη Καραγιάννη.

Συνέντευξη στο Δημήτρη Καραγιάννη.

Με την ευκαιρία της επίσκεψής του στην Ελλάδα, πριν μερικές μέρες, είχαμε την ευκαιρία να μιλήσουμε με τον Καμίλο Γκεβάρα, γιο του Ερνέστο Γκεβάρα ντε λα Σέρνα, του θρυλικού επαναστάτη Τσε. Ο 44χρονος Καμίλο, ταγμένος στην υπόθεση της Κουβανικής Επανάστασης, όπως μας λέει, έχει σπουδάσει Νομική και σήμερα μαζί με τη μητέρα του, Αλέιδα Γκεβάρα Μαρτς, διοικούν το Κέντρο Μελετών «Τσε Γκεβάρα» στην Αβάνα. Πρόκειται για ένα κέντρο που σκοπό του έχει να εκδώσει και να διαδώσει όλο το έργο του Τσε.

Με άμεσο, ζεστό και γεμάτο χιούμορ και ζωντάνια λόγο, όπως και οι περισσότεροι Κουβανοί, απάντησε στις ερωτήσεις μας, σε μια συνέντευξη που δίνει την ευκαιρία στον αναγνώστη, για άλλη μια φορά, να γνωρίσει αυτό τον περήφανο λαό, που εξακολουθεί να δίνει καθημερινά τον αγώνα του για αξιοπρέπεια και ακεραιότητα της πατρίδας του. Και στηρίζει το σοσιαλισμό που μέσα σε μεγάλες δυσκολίες οικοδομεί, ο οποίος έχει δώσει τεράστιες δυνατότητες στα λαϊκά στρώματα.

– Τιμή μας να μιλάμε μαζί σας. Επιτρέψτε μας μια πρώτη ερώτηση κάπως κοινότοπη. Εχετε ένα «βαρύ» όνομα, γεμάτο ιστορία. Τι σημαίνει αυτό για εσάς;

– Θα έλεγα ότι είναι βαρύ με την έννοια της αξίας για πολλούς ανθρώπους. Ας το διευκρινίσουμε όμως. Αυτό που συμβαίνει στην Κούβα, την πατρίδα μου, είναι ότι τους ανθρώπους δεν τους εκτιμάμε με βάση το όνομα. Το σημαντικό για τους Κουβανούς, και μιλάω με βάση την προσωπική μου εμπειρία, είναι να σε γνωρίσουν πρώτα, να σε εκτιμήσουν και να σε δεχτούν για τις αξίες και τα ελαττώματά σου. Και έτσι σου ανοίγεται ένας δρόμος στην κοινωνία που ζεις. Μπορείς ή όχι να βαδίσεις στη ζωή με τα δικά σου βήματα. Και νομίζω αυτό είναι σημαντικό. Βέβαια, μπορεί να συμβεί κάποιες φορές όταν κάνεις κάποιες επισκέψεις σε άλλες χώρες να σε «πλακώνουν» οι φωτογράφοι, όπως τώρα (λέει αστειευόμενος με τον φωτογράφο της εφημερίδας).

Αυτό είναι το κόστος που πρέπει να πληρώσεις για το όνομα. Πάντως, να ξέρετε ότι απέναντί σας έχετε έναν Κουβανό, ο οποίος έχει μιαν αντίληψη που είναι ταγμένη σε μια δίκαιη υπόθεση όπως η δική μας. Σε αυτό το πλαίσιο θα μπορούσα να απαντήσω στις ερωτήσεις σας.

Το κράτος εξασφαλίζει δυνατότητες εξέλιξης σε όλους

– Μιλήστε μας για τη δική σας εμπειρία. Πώς είναι να μεγαλώνει ένα παιδί στην Κούβα; Πώς διαμορφώνεται ως προσωπικότητα;

– Η Κούβα δίνει μεγάλη σημασία στην Παιδεία, σε όλα τα στάδια της εκπαίδευσης. Αυτή είναι, κατ’ αρχάς, η υποχρεωτική βασική εξάχρονη εκπαίδευση (μαζί με δίχρονη προσχολική) σε ένα απολύτως δημόσιο και δωρεάν εκπαιδευτικό σύστημα που εξασφαλίζει τα πάντα στο παιδί.

– Θεωρείτε αυτονόητη τη δωρεάν εκπαίδευση, σε πολλές όμως χώρες, και στη δική μας, η κατάσταση είναι πολύ διαφορετική και όνειρο για τα λαϊκά στρώματα.

– Το γνωρίζω, αλλά (αστειευόμενος) μιλάμε για την Κούβα. Επειτα από τη βασική εκπαίδευση ακολουθεί η δευτεροβάθμια, η προπανεπιστημιακή και η πανεπιστημιακή. Αλλά πρέπει να πούμε ότι υπάρχουν όλες οι προϋποθέσεις από το κράτος ώστε όλοι να φτάσουν μέχρι την ένατη τάξη και είναι μια από τις πολλές μάχες που δίνουμε ως λαός. Σήμερα, πάνω από το 90% των νέων το καταφέρνει. Ετσι, το να μεγαλώνεις σε μια κοινωνία όπου η συντριπτική πλειοψηφία έχει υψηλό μορφωτικό και πολιτιστικό επίπεδο σε βοηθάει να αναπτυχθείς.

Επίσης, υπάρχουν δυνατότητες για σπουδές στην προπανεπιστημιακή εκπαίδευση με βάση τα ενδιαφέροντα του ατόμου και ακολουθούν τα πανεπιστήμια εφόσον ο νέος έχει τα προσόντα. Αυτή την περίοδο γίνεται μεγάλη προσπάθεια να αυξηθούν οι δυνατότητες για όποιον θέλει να σπουδάσει να μπορεί να το κάνει. Επίσης, έχουν δημιουργηθεί συγκεκριμένα προγράμματα στα Μέσα Μαζικής Ενημέρωσης, όπως το λεγόμενο Πανεπιστήμιο για όλους. Υπάρχουν οι πανεπιστημιακές σχολές, αλλά και τα εργατικά πανεπιστήμια, μια παλιά κατάκτηση της πάλης του λαού μας. Υπάρχουν επίσης τα λεγόμενα Δημοτικά Πανεπιστήμια, που έχουν στόχο να φέρουν πιο κοντά στον πληθυσμό τη δυνατότητα μόρφωσης. Ιδιαίτερα τα τελευταία χρόνια υπάρχουν στους δήμους πανεπιστήμια για ηλικιωμένους που έχουν πολύ χρόνο και θέλουν να κάνουν ενδιαφέροντα πράγματα.

Το σημαντικότερο επίτευγμα του σοσιαλισμού είναι η ενεργοποίηση των μαζών

– Χωρίς να θέλω να διακόψω τη σκέψη σας, όλα αυτά ακούγονται σε μας, που βιώνουμε τα …δεδομένα του καπιταλισμού, αρκετά πρωτόγνωρα.

– Θα έλεγα ότι είναι πρωτόγνωρα και για άλλες σοσιαλιστικές εμπειρίες που έχουμε από το παρελθόν. Νομίζω όμως ότι αυτό που μπορεί να διαπιστωθεί στην Κούβα είναι ότι ο σοσιαλισμός είναι πολύ νέος, μια νέα υπόθεση που πρέπει να εξελιχθεί. Δεν πρέπει να δημιουργούμε δόγματα, πρέπει να επιδιώκουμε να εκφράζεται ο ίδιος ο λαός, τα ινστιτούτα της χώρας, στην πορεία της οικοδόμησης. Αυτό ανοίγει συνεχώς δρόμους. Νομίζω ότι το μεγαλύτερο ατού που έχει ο σοσιαλισμός είναι ότι έχεις τη δυνατότητα να φτάσεις στο μέγιστο που μπορούν να δώσουν οι μάζες. Και αυτό εξελίσσεται σε μια συνεχή δημιουργία, μέσα από όλες αυτές τις ευκαιρίες, που έχουν όμως το χαρακτήρα της ισότητας για όλους και σου επιτρέπουν να κάνεις όλα αυτά τα πράγματα. Αυτό είναι και το πιο σημαντικό επίτευγμα του σοσιαλισμού. Σε αυτό το πλαίσιο και σε αυτές τις στιγμές η Κούβα κάνει πολλά ενδιαφέροντα πράγματα.

Ξέχασα να πω ότι υπάρχει και ένα πανεπιστήμιο στις φυλακές. Γιατί, δυστυχώς, στην Κούβα υπάρχουν και φυλακές, δεν είμαστε τέλειοι. Δίνεται, λοιπόν, η δυνατότητα σε ανθρώπους που υπέπεσαν σε κάποιο ποινικό αδίκημα να πάρουν κάποια εφόδια που θα μπορούσαν, με τη δική τους θέληση, να τους βοηθήσουν μετέπειτα στη ζωή τους.

Αυτή είναι η κατάσταση στην Κούβα. Δε θέλω να πω ότι όλα είναι τέλεια αλλά γίνονται προσπάθειες. Εδώ βέβαια δεν πρέπει να ξεχνάμε την κατάσταση όπου ζει η Κούβα. Μόλις τώρα αρχίζει να ξεπερνάει μια βαθιά κρίση, στην οποία βρέθηκε ως συνέπεια των ανατροπών στις σοσιαλιστικές χώρες της Ανατολικής Ευρώπης, με τις οποίες είχαμε το 80% των εμπορικών συναλλαγών μας. Είναι σαν να έχεις έναν άνθρωπο που σχηματικά ζει με 10 δολάρια και ξαφνικά του παίρνουν τα 8 και πρέπει να ζήσει με τα 2 και να διατηρήσει όλα όσα είχε. Περάσαμε πολύ δύσκολα χρόνια το ’90-’95. Ξεπερνάμε αυτό το σοκ, όχι ότι είμαστε …σε διακοπές αλλά οι πιο δύσκολες εποχές πέρασαν και αρχίζουμε να επανακτούμε δυνάμεις στην οικονομία. Είναι αλήθεια – και χωρίς καμία διάθεση έπαρσης – ότι λίγες χώρες στον κόσμο μπορούν να το καταφέρουν αυτό.

– Αυτό άλλωστε είναι η πιο μεγάλη επιτυχία του κουβανικού λαού, ότι διατηρεί το σοσιαλισμό.

– Ετσι είναι. Αυτό είναι αποτέλεσμα της πάλης του λαού. Οχι όμως γενικά και αόριστα, αλλά κάτω από τη συγκεκριμένη καθοδήγηση και ηγεσία και τη συγκεκριμένη οργάνωση της κοινωνίας. Δεν μπορώ να πω ότι έχω δει παρόμοια περίπτωση στον κόσμο. Μιλάμε για μια χώρα που δε λάμβανε οικονομική βοήθεια από πουθενά, με ένα εγκληματικό εμπάργκο από την πιο μεγάλη δύναμη του πλανήτη, με την εξάλειψη του σοσιαλιστικού συστήματος και με πολύ χαμηλές διεθνείς τιμές στα προϊόντα της. Επίσης, πρέπει να υπολογίσουμε το κόστος για την εξασφάλιση της άμυνας της χώρας και τη διατήρηση των κοινωνικών κατακτήσεων.

Παρούσα η σκέψη του Τσε

– Εχετε μελετήσει σίγουρα τα έργα του πατέρα σας, τη σκέψη του για την ανάπτυξη της προσωπικότητας. Πιστεύετε ότι οι ιδέες του βρίσκουν εφαρμογή στην Κούβα;

– Εχετε μελετήσει σίγουρα τα έργα του πατέρα σας, τη σκέψη του για την ανάπτυξη της προσωπικότητας. Πιστεύετε ότι οι ιδέες του βρίσκουν εφαρμογή στην Κούβα;

– Νομίζω ότι οι ιδέες του Τσε είναι παρούσες. Ο Τσε δεν είναι βέβαια το άπαν. Ο Τσε πήρε τις αξίες που υπήρχαν μέχρι την εποχή του, τα θετικά του ανθρώπινου πολιτισμού και με τη δημιουργική του εργασία τις εμπλούτισε με έναν τρόπο αυθεντικό. Γι’ αυτό και μέχρι σήμερα είναι επίκαιρος και έχει σημασία για πολύ κόσμο. Βεβαίως, ο Τσε δεν ήταν μόνος του. Ανήκε σε μια μεγάλη ομάδα επαναστατών, ήταν μέλος ενός κινήματος, αργότερα του Κομμουνιστικού Κόμματος στα πλαίσια της Κουβανικής Επανάστασης και εμπνεόταν από τα ιδανικά μιας μεγάλης ομάδας σε όλο τον κόσμο που ήταν η πρωτοπορία της εποχής της, η οποία βρέθηκε στην εξουσία και έκανε πράξη τις ιδέες της.

Γι’ αυτό βλέπεις ότι η Κούβα, παρόλο που είναι μια φτωχή χώρα, μπορεί να στέλνει χιλιάδες γιατρούς σε κάθε γωνιά του πλανήτη σε όποιο λαό τους έχει ανάγκη. Αυτό σου δείχνει ένα διαφορετικό τρόπο σκέψης και δράσης, που εκφράζει ένα βαθύ ανθρωπισμό. Ετσι όπως πρέπει να είναι ο κόσμος. Αν εσύ έχεις πρόβλημα εγώ σου δίνω τη βοήθειά μου.

Οι ρίζες αυτής της σκέψης πηγάζουν απ’ ό,τι πιο θετικό έχει δώσει η ανθρωπότητα. Και πιστεύω ότι για να είναι κάποιος κομμουνιστής πρέπει πρώτα απ’ όλα να είναι βαθιά άνθρωπος. Και σε αυτό ο Τσε ήταν σημείο αναφοράς, ένα παράδειγμα. Ηταν ένας με όλη τη σημασία άνθρωπος. Ταγμένος σε μια υπόθεση που στην ουσία είναι βασική για να διατηρηθεί το είδος μας, γιατί σε αντίθετη περίπτωση θα εξαφανιστεί.

Το Κέντρο Μελετών «Τσε Γκεβάρα»

– Πείτε μας δυο λόγια για το Κέντρο Μελετών «Τσε Γκεβάρα», όπου βρίσκεστε. Ποιος ο σκοπός και το έργο του;

– Το Κέντρο ιδρύθηκε το 1984, ως προσωπικό αρχείο του Τσε στο σπίτι που έζησε στην Αβάνα, στο Νουέβο Βεδάδο. Ετσι, ξεκίνησε μια, θα έλεγα, ανώνυμη δουλιά, η ταξινόμηση και η συστηματοποίηση από επιστήμονες ώστε κάποια στιγμή να μπορέσουμε να εκθέσουμε αυτό το έργο, έχοντας και τη στήριξη της κουβανικής πολιτείας. Μπορούμε να πούμε ότι το Κέντρο έχει δύο κεντρικές κατευθύνσεις. Μια ακαδημαϊκή, που σημαίνει τη μελέτη των έργων, της σκέψης, της δράσης και της ζωής του Τσε. Να εμβαθύνουμε στη μελέτη και να προχωρήσουμε στην έκδοση των ανέκδοτων έργων του. Θέλουμε να εκδοθεί αυθεντικά ο Τσε με δικά του κείμενα και μετά θα έρθουν οι αναφορές και οι αναλύσεις για το έργο του. Θέλουμε να εκδώσουμε όλο του το έργο. Μέσα σε αυτή τη δουλιά υπάρχει μια σημαντική πλευρά, αυτή της διάδοσης του έργου του. Μελετάς το έργο, εμβαθύνεις σε αυτό, το εκδίδεις, αλλά πρέπει και να το διαδώσεις. Ετσι, κάνουμε ντοκιμαντέρ, ψηφιακά προγράμματα στο Ιντερνετ και άλλες εκδόσεις για πιο νέους ανθρώπους, αδιαμόρφωτους, όπως περιοδικά που μπορούν να προσεγγίσουν πιο κατανοητά τον Τσε.

Δεύτερη κατεύθυνση της δουλιάς μας είναι να γίνει το Κέντρο και κέντρο προβολής πολιτισμού, ώστε να αναδειχτούν οι ανθρώπινες αξίες. Εχουμε φτιάξει κοινότητες επικοινωνίας κυρίως με νέους αλλά και παιδιά. Θέλουμε όχι μόνο να επηρεάζει το Κέντρο αλλά και το κοινό μας με βάση τα ενδιαφέροντά του, ώστε να εμβαθύνουμε στις ανθρώπινες αξίες.

– Υπάρχει ενδιαφέρον από τη νεολαία;

– Υπάρχει σημαντικό ενδιαφέρον. Ηδη έχουμε εκδώσει κάποια έργα και επίσης πραγματοποιούμε εκδηλώσεις και άλλες δραστηριότητες. Πρόσφατα γυρίστηκε η ταινία «Το ημερολόγιο της Μοτοσικλέτας», του Βραζιλιάνου σκηνοθέτη Βάλτερ Σάλας. Επίσης, έχουμε εκδώσει το «Ημερολόγιο του Κονγκό», «Το δεύτερο ταξίδι στη Λατινική Αμερική» και πρόκειται να εκδώσουμε το βιβλίο «Η οικονομική σκέψη του Τσε» και σειρά από ανέκδοτα κείμενα. Μιλάμε επίσης γι’ αυτά που ονομάζουμε τα «Φιλοσοφικά του τετράδια», κείμενα που έγραψε από τα 17 του χρόνια μέχρι τη Βολιβία. Εκεί βλέπουμε και την ωρίμανση, τη διανοητική εξέλιξη της σκέψης του Τσε, που είναι μια καλή απεικόνιση του διανοητικού δρόμου που ακολούθησε. Και βέβαια αυτή την εργασία δεν μπορούμε να την εκδώσουμε ανεπεξέργαστη, γιατί αυτό μπορεί να μπερδέψει τον αναγνώστη για την πορεία εξέλιξης του Τσε. Γι’ αυτό χρειάζεται να κάνουμε μια μελετητική δουλιά με φιλοσόφους, κοινωνιολόγους και άλλους επιστήμονες. Επίσης, πρέπει να γίνει κατανοητή η πολιτιστική εξέλιξή του για να κατανοηθεί η οικονομική του σκέψη. Ο Τσε ήταν ένας άνθρωπος που ενώ εργαζόταν ως υπουργός Βιομηχανίας μελετούσε ακατάπαυστα. Σπούδασε λογιστικά, οικονομικές επιστήμες, μαθηματικά και έφτασε σε πολύ υψηλό επίπεδο. Κατά τη διάρκεια της θητείας του στο υπουργείο Βιομηχανίας. Μελετούσε πάντα, παντού και τα πάντα. Ολα αυτά εξηγούν γιατί η σκέψη του είναι βαθιά. Εφτανε στην ουσία των πραγμάτων.

– Ας πάμε σε κάτι άλλο. Η εικόνα του Τσε έχει αρκετά εμπορευματοποιηθεί. Τη βλέπουμε στις φανέλες, στα μπουκάλια, σε άλλα προϊόντα. Χρησιμοποιείται και σαν άλλοθι για να κρύβεται αυτό που ο Τσε ήταν. Αγιοποιούν τον Τσε για να τον ακυρώσουν; Το σύστημα τον χρησιμοποιεί; Τι λέτε γι’ αυτό;

– Κοιτάξτε, το Κέντρο έχει ως βασική λειτουργία να διαδώσει τη σκέψη του Τσε. Δεν μπορούμε να αλλάξουμε τον κόσμο με μια κίνηση. Χρειάζεται χρόνος και δουλιά για να αλλάξουν τα πράγματα. Το πιο σημαντικό στον Τσε, κατά τη γνώμη μας, είναι η σκέψη του. Γι’ αυτό, πρώτον, πρέπει να εκδώσουμε αυτό το έργο, να βοηθήσουμε τον κόσμο να το καταλάβει. Μετά να συνδυάσουμε την εικόνα του. Δεν μπορούμε να πούμε στον κόσμο να μη βλέπει την εικόνα του. Αυτός εξάλλου είναι ο Τσε, μαζί του είναι και η ιστορία του. Η προσπάθεια να παρουσιαστεί ως «μύθος» και μόνο, είναι για να τον σκοτώσουν για δεύτερη φορά, αυτή τη φορά τελικά. Εμείς έχουμε σχεδιασμένη μια στρατηγική. Το πρώτο είναι η σκέψη του Τσε. Αν κάποιος θέλει να τον έχει στην μπλούζα του ή στο ποτήρι του, στο δίσκο του, ωραία, εμείς θέλουμε να του πούμε τι είναι αυτό που συμβολίζει.

Ενας αγωνιστής λαός με ιστορία

– Μια τελευταία ερώτηση που ενδιαφέρει κάθε άνθρωπο ο οποίος έχει ανησυχίες και βλέπει την τιτάνια προσπάθεια που κάνει ο κουβανικός λαός. Τι είναι αυτό που τον κάνει να στέκεται όρθιος παρά τις τεράστιες δυσκολίες;

– Νομίζω ότι αυτό συμβαίνει λόγω της ιστορίας που είχε αυτός ο λαός. Πάντα αντιστεκόταν ενάντια σε ισχυρούς εχθρούς. Μια μικρή χώρα που έχει περάσει από μεγάλους αγώνες. Η δική μας ιστορία είναι πολύ νέα. Το έθνος μας είναι πολύ νέο και έχει πολλούς νέους ανθρώπους. Με τη νίκη της επανάστασης ήμασταν 6 εκατομμύρια, σήμερα είμαστε 11 εκατομμύρια. Πάντα ήμασταν αγωνιστικός λαός. Ο πόλεμος της ανεξαρτησίας ενάντια στην Ισπανία διάρκεσε 30 χρόνια, με ελάχιστα τεχνικά μέσα, με τα σπαθιά απέναντι σε κανόνια, και ήταν νικηφόρος για τους Κουβανούς. Μετά ήρθαν οι γιάνκηδες. Αυτό δίνει ένα περίγραμμα για το τι έκανε αυτός ο λαός. Είναι μια μείξη φυλών και πολιτισμών, ένας κόσμος σε ένα νησί. Και στο τέλος τέλος όλα όσα μας έκαναν οι εχθροί, οδήγησαν στο να ωριμάσει ο λαός και να διαμορφωθεί πάνω στις αξίες της αξιοπρέπειας και της ακεραιότητας. Και μπορώ να πω, κάνοντας και λίγο χιούμορ, ευτυχώς ή δυστυχώς, οι ΗΠΑ είναι λίγο έξυπνες όλα αυτά τα χρόνια, και αυτό μας υποχρεώνει να παλεύουμε συνεχώς.

Επίσης, αν δεν είχε ο σοσιαλισμός τη στήριξη του κόσμου και της νεολαίας, που είναι το μισό του πληθυσμού και βέβαια γεννήθηκε μετά την επανάσταση, δε θα μπορούσε να επιβιώσει σε απόσταση 90 μίλια από τις ΗΠΑ. Ο κόσμος κάνει αυτό που αισθάνεται και είναι ψέμα ότι οι μεγάλες διαδηλώσεις που διοργανώνουμε συχνά στο νησί είναι γιατί μας υποχρεώνουν. Φυσικά, τίποτα δεν είναι τέλειο, αλλά αυτή η κινητοποίηση του κόσμου δείχνει πολλά πράγματα. Είμαστε μια χώρα με σημαντικό πολιτισμό, εν πολλοίς ομοιογενή, και έχουμε έναν εχθρό που μας κάνει καθημερινά να συνειδητοποιούμε ότι απειλούμαστε. Ολα αυτά κάνουν τον κόσμο να είναι σε συνεχή επαγρύπνηση.

Αναδημοσίευση από το «Ριζοσπάστη», 12 Φλεβάρη 2006.

Che Guevara, a symbol of struggle (Part Two)

By Tony Saunois.

During this second tour Che penned another journal which he entitled, Otra Vez (Once Again).* Reflecting how he began this journey he wrote: «This time, the name of the sidekick has changed, now Alberto is called Calica, but the journey is the same: two disperse wills extending themselves through America without knowing precisely what they seek or which way is north.»

Che and companion arrived in La Paz, the Bolivian capital, during July 1953. They were immediately caught up in the revolutionary upheavals which were rocking one of the poorest and most «Indian» of American nations. A mass revolt of the predominantly indigenous peasants and tin miners had broken out twelve months earlier. This mass uprising had brought the radical Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR) to power.

The new regime, whilst trying to keep the mass movement in check, was forced by the insurrectionary upheavals to carry through a widespread programme of reform. The peasants, through a series of land occupations, forced a far reaching programme of agrarian change. The tin mines, Bolivia’s primary source of income at the time, were nationalised. The miners and peasants had armed themselves, sections of the army came over to the side of the workers and peasants. A militia was established and for a short time the army was formally disbanded. However, the revolution was not completed with the establishment of a new regime of workers’ democracy and the movement was eventually defeated.

During these revolutionary events the tin miners played a leading role in establishing a new independent trade union centre, the Central Obrera Boliviana (COB). Reflecting the revolutionary upsurge which took place the COB even formally endorsed the Transitional Programme, written by Leon Trotsky in 1938.

In La Paz, Che spent much of his time in cafes and bars meeting political migrants who had arrived from all over America. During the course of the revolution Bolivia had become a political Mecca as radicals and left-wing revolutionaries were attracted to the stormy events erupting.

«La Paz is the Shanghai of the Americas. A rich gamut of adventurers of all the nationalities vegetate and flourish in the polychromatic and mestizo city», wrote Che in his Otra Vez. Here he mixed with a variety of political activists and engaged in debate and discussions with them. He met up with some of the Argentine community living in La Paz. Amongst those he met was an exiled Argentinean, called Nogues.

The influence of the powerful social events taking place in Bolivia are reflected in Che’s comments about this leader of the expatriate Argentinean community. «His political ideas have been outdated in the world for some time now, but he maintains them independently of the proletarian hurricane that has been let loose on our bellicose sphere.»

Through these social contacts Che led a double existence in La Paz alternating between observing the revolutionary movements and the high life he was introduced to through the Argentine community. On one occasion, Nogues’ brother, having recently returned from Europe, showed Che and Calica an invitation he had received to the wedding of Greek shipping tycoon, Aristotle Onassis.

However, it was the revolutionary process which he witnessed in La Paz which left the most lasting impression on Che. He wrote to his father in July complaining that he wanted to stay in Bolivia longer because, «…this is a very interesting country and it is living through a particularly effervescent moment. On the second of August the agrarian reform goes through, and fracases and fights are expected throughout the country. We have seen incredible processions of armed people with Mausers and ‘piripipi’ (machine guns), which they shoot off for the hell of it. Every day shots can be heard and there are wounded and dead from firearms.»

Che, who wanted to see the renowned Bolivian miners first hand, visited the Balsa Negra mine just outside La Paz. Prior to the revolution company guards had used a machine gun to open fire on striking miners. Now the mine was nationalised. Che encountered truck loads of armed miners returning from the capital to protest their support for land reform and the struggle of peasants. With their «stony faces and red plastic helmets they appeared to be warriors from other worlds».

Despite witnessing the tremendous strength of the Bolivian miners Che never really absorbed the potential role of the working class in the socialist revolution, even in countries such as Bolivia where they constituted a minority of the population. This weakness, combined with other factors, would have a direct bearing on the ideas he later developed.

At this stage in Che’s political evolution however, it is sufficient to note the impact which events in Bolivia had on his outlook. For the first time in his life he was touched directly by the heat of the flame of revolution. Despite the sweep of events he was still an observer rather than an active participant.

After extending their stay in La Paz to nearly one month Che and Calica moved on. They spent some time in Peru and in Lima again met with Doctor Pesce and also Gobo Nogues. Gobo ensured that they ate on a few occasions at the Country Club and in Lima’s most expensive hotel, the Gran Hotel Bolívar.

They moved on to Ecuador where they forged new friendships with a group of adventurers. Che’s intention had been to move on with Calica to Venezuela. After a series of excursions Calica and Che departed company, the former heading for Caracas and the latter with a new companion, Gualo, to Guatemala. They were totally broke and had to work their passage on a ship. Before reaching Guatemala they passed through Costa Rica, Panama and Nicaragua, meeting and discussing with individuals and groups along the way.

By travelling north to Central America Che had entered a somewhat different world to that which existed in the southern cone of Latin America. Imperialism dominated the southern countries in conjunction with an enfeebled national capitalist class. There was a relatively strong urban population and working class in the cities and the societies tended to be more developed. This was even the case in the poorest countries at the time, such as Bolivia and Peru.

In a series of Central American countries US imperialism arrogantly imposed local tyrants as dictatorial heads of state while despised and hated companies, such as Coca Cola and the United Fruit Company, plundered the economies. As Che commented: «…the countries were not true nations, but private estancias».

This was only fifty years after US imperialism had created Panama, and ran it as a client state in order to keep control of the canal which it had built for trade purposes and strategic interests. Nicaragua had been ruled for thirty years by the corrupt dictatorship of Somoza. El Salvador was run by a succession of dictatorships intent on defending the interests of the coffee plantation owners, and Honduras was virtually run as a packaging plant for the United Fruit Company.

The United Fruit Company symbolised the exploitation of the continent by imperialism. Che’s favourite poet, Pablo Neruda, wrote an ironical verse, La United Fruit Co., reflecting the sentiments of Latin America towards its imperialist domination.

Neruda’s poem continues and denounces the company for creating the «Tyrannical Reign of Flies» the dictators of Central America: Trujillo, Tachos, Ubico, Martínez, Garias – «the bloody domain of flies.»

On to Guatemala

If events in Bolivia had made an impact on Che, developments in Guatemala, where he got actively involved for the first time, would change the direction of his life. He arrived in Guatemala City on Christmas Eve and openly identified with a political cause and with some idea of what he now intended to commit his life to.

Just prior to his arrival he had written a letter dated December 10, in which he outlined his political views to his aunt Beatríz, with whom he had an especially close relationship. These were undoubtedly a reflection of the effect events in Bolivia had had on him. For the first time he clearly identified himself ideologically with socialist ideas.

«My life has been a sea of found resolutions until I bravely abandoned my baggage and, back pack on my shoulder, set out with el compañero García on the sinuous trail that has brought us here. Along the way I have had the opportunity to pass through the dominions of the United Fruit, convincing me once again of just how terrible these capitalist octopuses are. I have sworn before a picture of the old and mourned Stalin that I won’t rest until I see these capitalist octopuses annihilated. In Guatemala I will perfect myself and achieve what I need to be an authentic revolutionary.» He signed the letter «from your nephew of the iron constitution, the empty stomach and the shining faith in the socialist future. Chao, Chancho».

By 1953 the populist left-leaning government in Guatemala, presided over by Colonel Jacobo Arbenz, was locked into a head-on confrontation with US imperialism and the rich elite of Guatemala City. Arbenz was continuing a reformist programme begun by the preceding government which came to power during the 1940’s having toppled the ruthless Ubico dictatorship.

US imperialism would tolerate a lot from this reformist administration. But in 1952 the Arbenz administration took a step too far. A land reform decree was enacted which abolished the latifundia system and nationalised the properties of the detested United Fruit Company.

This measure provoked the wrath of Guatemala’s white Creole elite and won massive support from the mainly indigenous and mestizo poor rural peasants and urban workers. The United Fruit Company and the Eisenhower administration were outraged. It would only be a matter of time before the CIA would instigate the overthrow of the Arbenz government.

The «socialist» experiment in Guatemala had drawn thousands from all over Latin America to see first hand this challenge to US imperialism. Mass mobilisations were taking place all the time and numerous militias were established by both the government and the various political parties. In the main these were not armed. However, the forces of reaction began to arm and mobilise.

Amongst those present during the Guatemalan drama, apart from Che Guevara, were numerous future leaders of Latin American left-wing organisations, including Rodolfo Romero, a future leader of the Nicaraguan Sandinista FSLN (Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional) which overthrew the Somoza dictatorship in 1979.

Che met with a series of political activists and engaged in discussion. He secured work as a doctor in a hospital and was introduced to Hilda Gadea, an exiled leader of the youth wing of the radical populist Peruvian movement, APRA. She introduced him to activists and leaders of various political groupings and gave him political works to study, including some works of Mao Tse Tung.

It was during these events that Che encountered a number of Cuban exiles. They had been given asylum by the Arbenz regime and had participated in an attempted assault on July 26 1953 against the Moncada military barracks in Cuba. For the first time Che began to discover about the struggle developing against the Cuban Batista regime.

The speed with which events developed in Guatemala also resulted in Che’s ideas maturing. He began to criticise the communist parties which had adopted a policy of ‘Popular’ or ‘People’s Fronts’. This put them in alliances with sections of the national capitalist class. The leadership of the communist parties wrongly argued a tactical alliance with this «progressive» wing of the national capitalist class was necessary in the struggle against imperialism, in order to defend and widen parliamentary democracy. They said a stage of ‘capitalist democracy and economic development’ was necessary before the working class could struggle for and hope to obtain socialism.

This policy resulted in the communist party leaders limiting the struggles of the working class to prevent them challenging the interests of capitalism. The workers’ movement was frequently paralysed by this policy which often resulted in bloody defeat at the hands of reaction. Decisive sections of the capitalist class were quite prepared to abolish democratic rights and utilise repressive methods of rule in order to defend their own class interests.

Che, although not clearly presenting an alternative to this policy, felt that the communist parties were moving away from the masses simply to get a share of power in a coalition government. He wrongly argued at this time that no party in Latin America could remain revolutionary and contest elections.

Though beginning to articulate his thoughts, Che’s ideas did not become fully formulated until later. Meanwhile, events in Guatemala overtook the polemics he had begun to be engaged in. The US was increasingly uneasy about the course events were taking and had concluded the government must be overthrown. The example of the movement in Guatemala was beginning to spill over into other Central American countries. A general strike broke out in Honduras. The Nicaraguan dictator, Somoza, feared his own population may follow the example of events in neighbouring countries.

The CIA had put together a plan to topple the Guatemalan administration. A figure-head named Castillo Armas was hand-picked to replace Arbenz as President. A paramilitary force was trained in Nicaragua and those friendly to the US in the Guatemalan Army were involved in a plot against the government.

Arbenz refused to take action against those in the military known to be sympathetic to the plotters and tried to appease the military. A few days before his government was overthrown in 1954 by the conspirators he appealed to the army itself to distribute arms to the militias which had been established. The military command refused and the government fell. The existing capitalist state machine had been left intact and no alternative of workers’ and peasants’ committees had been established from which an appeal could have been made to the rank and file soldiers.

This defeat and the failure of Arbenz to take any action against the capitalist state apparatus was to leave a lasting impression on Che, one which he would not forget as the revolution in Cuba unfolded.

After seeking asylum in the Argentinean Embassy and hiding for a period, Che eventually found his way to Mexico by September. As a fresh activist his movements had not gone unnoticed. The CIA opened a file on him for the first time. Over the coming years it was to become one of the thickest ever compiled by them on any one individual.

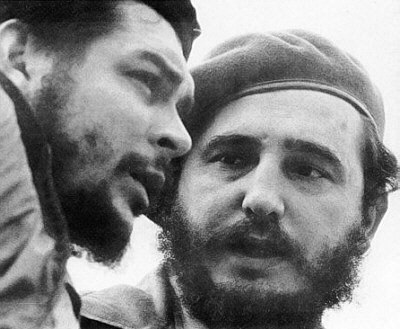

It was while Che was in Mexico that he initially met one of the leaders of the July 26th Movement fighting the Batista dictatorship in Cuba, Fidel Castro. Their first meeting was during 1955, after which Che eventually joined the Movement.

Following his experiences in Bolivia and in particular after his participation in events in Guatemala, Che entered the next phase of his life no longer as the medical doctor and social observer. From this point on he was to be an active participant in and eventual leader of historic events.

Source: socialistworld.net.

Οι απόψεις που εκφράζονται στο άρθρο δεν υιοθετούνται απ’ το Ελληνικό Αρχείο Τσε Γκεβάρα.

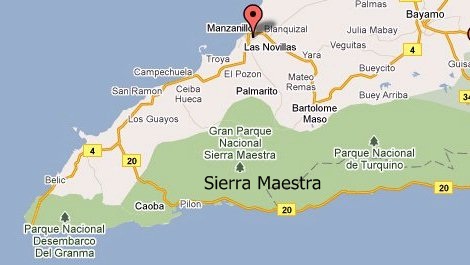

Σιέρρα Μαέστρα (Sierra Maestra)

Το όνομα της Σιέρρα Μαέστρα (Sierra Maestra) είναι άρρηκτα συνδεδεμένο με την Κουβανική Επανάσταση και, επομένως, με τον ίδιο τον Τσε. Η οροσειρά που βρίσκεται στα δυτικά της επαρχίας Οριέντε, στο νότιο άκρο της Κούβας, έχει υπάρξει μάρτυρας σημαντικών ανταρτοπολέμων – από τον Πόλεμο των Δέκα Ετών επί ισπανικής αποικιοκρατίας στα μέσα του 19ου αιώνα μέχρι τον αγώνα γιά την Κουβανική ανεξαρτησία και φυσικά τη δράση του Επαναστατικού Κινήματος της 26ης Ιουλίου ενάντια στο καθεστώς Μπατίστα. Στις δύσβατες βουνοπλαγιές της Σιέρρα Μαέστρα ο Φιντέλ Κάστρο και οι σύντροφοι του οργάνωσαν τον αντάρτικο αγώνα ενάντια στα στρατεύματα της Κουβανικής δικτατορίας, δίνοντας μιά θρυλική – ιστορικής σημασίας – διάσταση στα απόκρυμνα δάση της επαρχίας Οριέντε.

Το όνομα της Σιέρρα Μαέστρα (Sierra Maestra) είναι άρρηκτα συνδεδεμένο με την Κουβανική Επανάσταση και, επομένως, με τον ίδιο τον Τσε. Η οροσειρά που βρίσκεται στα δυτικά της επαρχίας Οριέντε, στο νότιο άκρο της Κούβας, έχει υπάρξει μάρτυρας σημαντικών ανταρτοπολέμων – από τον Πόλεμο των Δέκα Ετών επί ισπανικής αποικιοκρατίας στα μέσα του 19ου αιώνα μέχρι τον αγώνα γιά την Κουβανική ανεξαρτησία και φυσικά τη δράση του Επαναστατικού Κινήματος της 26ης Ιουλίου ενάντια στο καθεστώς Μπατίστα. Στις δύσβατες βουνοπλαγιές της Σιέρρα Μαέστρα ο Φιντέλ Κάστρο και οι σύντροφοι του οργάνωσαν τον αντάρτικο αγώνα ενάντια στα στρατεύματα της Κουβανικής δικτατορίας, δίνοντας μιά θρυλική – ιστορικής σημασίας – διάσταση στα απόκρυμνα δάση της επαρχίας Οριέντε.

Το υψηλότερο σημείο της οροσειράς είναι το Πίκο Τουρκίνο φτάνοντας τα 1.974 μέτρα. Στην κορυφή υπάρχει προτομή του πρωτεργάτη της Κουβανικής ανεξαρτησίας, Χοσέ Μαρτί. Η γύρω περιοχή από το Πίκο Τουρκίνο αποτελεί Εθνικό Πάρκο εκτάσεως περίπου 230 τετραγωνικών χιλιομέτρων.

Che’s ideas are absolutely relevant today: A speech by Fidel Castro (Part Four)

Starting out from the idea that rectification means, as I’ve said before, looking for new solutions to old problems, rectifying many negative tendencies that had been developing; that rectification implies making more accurate use of the system which, as we said at the enterprises meeting, was a horse, a lame nag with may sores that we were treating with mercurochrome and prescribing medicines for, putting splints on one leg, in short, fixing up the nag, the horse. I said that the thing to do now was to go on using that horse, knowing its bad habits, the perils of that horse, how it kicked and bucked, and try to lead it on our path and not go wherever it wishes to take us. I’ve said, let us take up the reins!

Starting out from the idea that rectification means, as I’ve said before, looking for new solutions to old problems, rectifying many negative tendencies that had been developing; that rectification implies making more accurate use of the system which, as we said at the enterprises meeting, was a horse, a lame nag with may sores that we were treating with mercurochrome and prescribing medicines for, putting splints on one leg, in short, fixing up the nag, the horse. I said that the thing to do now was to go on using that horse, knowing its bad habits, the perils of that horse, how it kicked and bucked, and try to lead it on our path and not go wherever it wishes to take us. I’ve said, let us take up the reins!

These are very serious, complicated matters and here we can’t afford to take shots in the dark, and there’s no place for adventure of any kind. The experience of so many years that quite a few of us have had the privilege of accumulating through a revolutionary process is worth something. And that’s why we say now, we cannot continue fulfilling the plan simply in terms of monetary value! We must also fulfill it in terms of goods produced. We demand this categorically, and anyone who does otherwise must be quickly replaced, because there’s no other choice! We maintain that all projects must be started and finished quickly so that there is never a repeat of what happened to us on account of the nag’s bad habits: that business of doing the earthmoving and putting up a few foundations because that was worth a lot and then not finishing the building because that was worth little; that tendency to say, “I fulfilled my plan as to value but I didn’t finish a single building,” which made us waste hundred of millions, billions, and we never finished anything.

It took fourteen years to build a hotel. Fourteen years wasting iron bars, sand, stone, cement, rubber, fuel, manpower before the country made a single penny from the hotel being used. Eleven years to finish our hospital here in Pinar del Río! It’s true that in the end it was finished and it was finished well, but things of this sort should never happen again. The minibrigades, which were destroyed for the sake of such mechanisms, are now rising again from their ashes like a phoenix and demonstrating the significance of that mass movement the significance of that revolutionary path of solving the problems that the theoreticians, technocrats, those who do not believe in man, and who believe in two-bit capitalism had stopped and dismantled. This was how they were leading us into critical situations.In the capital, where the minibrigades emerged, it pains us to think that over fifteen years ago we had found an excellent solution to such a vital problem, and yet they were destroyed in their peak moment. And so we didn’t even have the manpower to building housing in the capital; and the problems kept piling up, tens of thousands of homes were propped up and were in danger of collapsing and killing people.

Now the minibrigades have been reborn and there are more than 20,000 minibrigades members in the capital. They’re not in the contradiction with the nag, with the Economic Management and the Planning System, simple because the factory or workplace that sends them to the construction site pays them, but the state reimburses the factory or workplace for the salary of the minibrigades member. The difference is that whereas the worker would normally work five or six hours, on the minibrigades he works ten, eleven or twelve hours doing the job of two or three men, and the enterprise saves money.

Our two-bit capitalist can’t say his enterprise is being ruined. On the contrary, he can say, “They’re helping the enterprise. I’m doing the job with thirty, forty or fifty less men and spending less on wages.” He can say, “I’m going to be profitable or at least lose less money; I’ll distribute more prizes and bonuses since wage expenditures will be cut down.” He organizes production better, he gets housing for his workers, who in turn are happier because they have new housing. He builds community projects such as special schools, polyclinics, day-care centers for the children of working women, for the family; in short, some many extremely useful things we are doing now and the state is building them without spending an additional cent in wages. That really is miraculous! We could ask the two-bit capitalists and profiteers who have blind faith in the mechanisms and categories of capitalism: Could you achieve such a miracle? Could you manage to build 20,000 housing units in the capital without spending a cent more on wages? Could you build fifty day-care centers in a year without spending a cent more on wages, when only five had been included in the five-year plan and they weren’t even built, and 19,5000 mothers were waiting to get their children a place, which never materialized.

At that rate, it would take 100 years! By then they would be dead, and fortunately so would all the technocrats, two-bit capitalists, and bureaucrats who obstruct the building of socialism. They would have died without ever seeing day-care center number 100. Workers in the capital will have their 100 day-care centers in two years, and workers all over the country will have the 300 or so they need in three years. That will bring enrollment to 70,000 or 80,000 easily, without paying out an additional cent in wages or adding workers, because at that rate with overstaffing everywhere, we would have ended up bring workers in from Jamaica, Haiti, some Caribbean island, or some other place in the world. That was where we were heading.It can be seen in the capital today that one in eight workers can be mobilized, I’m sure. This is not necessary because there would not be enough materials to give tasks to 100,000 people working Havana, each one doing the work of three. We’re seeing impressive examples of feats of work, and this achieved by mass methods, by revolutionary methods, by communist methods, combining the interests of people in need with the interests of factories and those of society as a whole.

I don’t want to become the judge of different theories, although I know what things I believe in and what things I don’t and can’t believe in. These questions are discussed frequently in the world today. And I only ask modestly, during the problem of rectification, during this process of this struggle — in which we’re going to continue as we already explained: with the old nag, while it can still walk, if it walks, and until we can cast it aside and replace it with a better horse as I think that nothing is good if it’s done in a hurry, without analysis and deep thought — What I ask for modestly at this twentieth anniversary is that Che’s economic thought be made known; that it be known here, in Latin America, in the world; in the developed capitalist world, in the Third World, and in the socialist world. Let it be known there too! In the same way that we may read many texts, of all varieties, and many manuals, Che’s economic thought should be known in the socialist camp. Let it be known! I don’t say they have to adopt it; we don’t have to get involved in that. Everyone must adopt the thought, the theory the thesis they consider most appropriate, that which best suits them, as judged by each country. I absolutely respect the right of every country to apply the method or systems it considers appropriate; I respect it completely!

I simply ask that in a cultured country, in a cultured world, in a world where ideas are discussed, Che’s economic theories should be made known I especially ask that our students of economics, of whom we have many and who read all kinds of pamphlets, manuals, theories abut capitalist categories and capitalist laws, also begin to study Che’s economic thought, so as to enrich their knowledge. It would be a sign of ignorance to believe there is only way of doing things arising from the concrete experience of a specific time and specific historical circumstances. What I ask for, what I limit myself to asking for, is a little more knowledge, consisting of knowing about other points-of-view, points-of-view as respected, as deserving and as coherent as Che’s points-of-view.

I simply ask that in a cultured country, in a cultured world, in a world where ideas are discussed, Che’s economic theories should be made known I especially ask that our students of economics, of whom we have many and who read all kinds of pamphlets, manuals, theories abut capitalist categories and capitalist laws, also begin to study Che’s economic thought, so as to enrich their knowledge. It would be a sign of ignorance to believe there is only way of doing things arising from the concrete experience of a specific time and specific historical circumstances. What I ask for, what I limit myself to asking for, is a little more knowledge, consisting of knowing about other points-of-view, points-of-view as respected, as deserving and as coherent as Che’s points-of-view.

I can’t conceive that our future economists, that our future generations will act, live and develop like another species of little animal, in the case like the mule, who has those blinders only so that he can’t see to either side; mules, furthermore, with grass and carrot dangling in front as their only motivation. No, I would like them to read, not only to intoxicate themselves with certain ideas, but also to look at other ones, analyze them, and think about them. Because if we are talking with Che and we said to him, “Look, all this has happened to us,” all those things I was talking about before, what happened to us in construction, in agriculture, in industry, what happened in the terms of goods actually produced, work quality, and all that, Che would have said, “It’s as I warned, what’s happening is exactly what I thought would happen,” because that’s simply the way it is. I want our people to be a people of ideas, of concepts. I want them to analyze those ideas, think about them, and if they want, discuss them. I consider these things to be essential.

It might be that some of Che’s ideas are closely linked to the initial stages of revolution, for example his belief that when a quota was surpassed, the wages received should not go above that received by those on the scale immediately above. What Che wanted was for the worker to study, and he associated his concept with the idea that our people who in those days had very poor education and little technical expertise should study. Today our people are much better educated, more cultured. We could discuss whether now they should earn as much as the next level or more. We could discuss questions associated with our reality of a far more educated people, a people far better prepared technically, although we must never give up the idea of constantly improving ourselves technically. But many of Che’s ideas are absolutely relevant today, ideas without which I am convinced communism cannot be built, like the idea that man should not be corrupted; that man should never be alienated; the idea that without consciousness, simply producing wealth, socialism as a superior society could not be built, and communism could never be built.

I think that many of Che’s ideas — many of his ideas! — have great relevance today. Had we known, had we learned about Che’s economic thought we’d be a hundred times more alert, including in riding the horse, and whenever the horse wanted to turn left of right, wherever it wanted to turn — although, mind you, here this was without a doubt a right-wing horse — we should have pulled it up hard and got it back on track, and whenever it refused to move, used the spurs hard. I think a rider, that is to say, an economist, that is to say, a party cadre, armed with Che’s ideas would be better equipped to lead the horse along the right track. Just being familiar with Che’s thought, just knowing his ideas would enable him to say, “I’m doing badly here, I’m doing badly there, that’s a consequence of this, that, or the other,” provided that the system and mechanisms for building socialism and communism are really being developed and improved on.

Read Part Five.

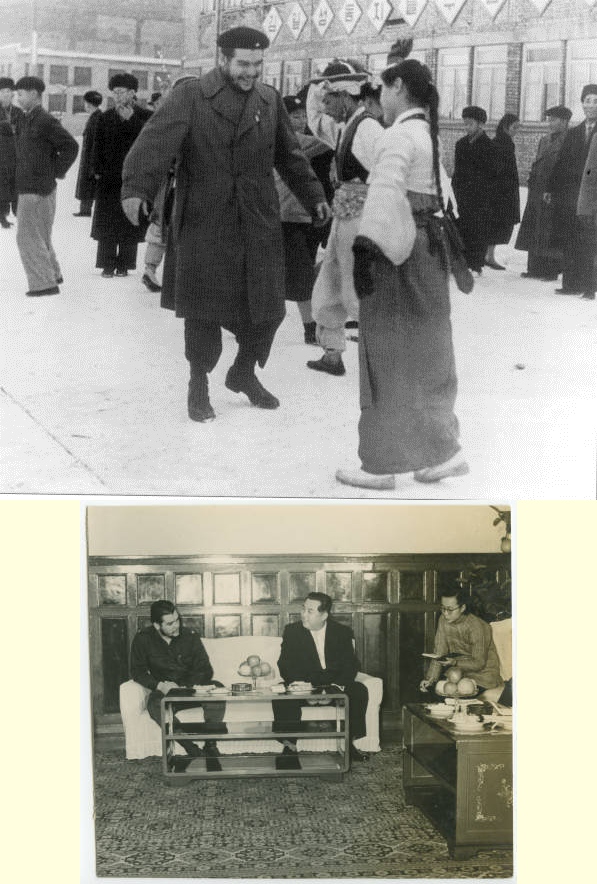

Ο Τσε στη Βόρειο Κορέα / Che Guevara in North Korea (DPRK)

Στιγμιότυπα από δύο επισκέψεις του Τσε Γκεβάρα στην Πιονγιάνκ της Βόρειας Κορέας. Στην πρώτη φωτογραφία (το 1960) ο Τσε δοκιμάζει τις χορευτικές του ικανότητες σε παραδοσιακό βορειοκορεάτικο χορό ενώ στη δεύτερη (1964 ή 1965) συνομιλεί με τον πρόεδρο Κιμ Ιλ-Σούνγκ.

Στιγμιότυπα από δύο επισκέψεις του Τσε Γκεβάρα στην Πιονγιάνκ της Βόρειας Κορέας. Στην πρώτη φωτογραφία (το 1960) ο Τσε δοκιμάζει τις χορευτικές του ικανότητες σε παραδοσιακό βορειοκορεάτικο χορό ενώ στη δεύτερη (1964 ή 1965) συνομιλεί με τον πρόεδρο Κιμ Ιλ-Σούνγκ.

Τηλεοπτικό απόσπασμα της επίσκεψης του Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα στην Πιονγιάνγκ της Βόρειας Κορέας το Δεκέμβρη του 1960. Όντας πρέσβης καλής θελήσεως της επαναστατικής κυβέρνησης της Κούβας ο Τσε συναντήθηκε με τον πρόεδρο της χώρας Κιμ Ιλ-Σούνγκ.