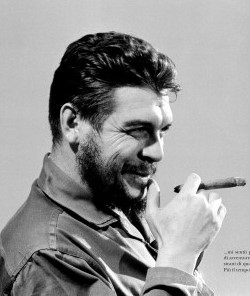

Ελληνικό Αρχείο Τσε Γκεβάρα © Guevaristas

Η πρώτη και πληρέστερη ελληνική ιστοσελίδα για τον Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα.

Ελληνικό Αρχείο Τσε Γκεβάρα © Guevaristas

Η πρώτη και πληρέστερη ελληνική ιστοσελίδα για τον Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα.

The questions below were submitted, in writing, to Comandante Guevara by Leo Huberman during the week of the Bay of Pigs invasion; the answers were received the end of June 1961.

The questions below were submitted, in writing, to Comandante Guevara by Leo Huberman during the week of the Bay of Pigs invasion; the answers were received the end of June 1961. Ο Ραούλ Μοδέστο Κάστρο Ρούζ, όπως είναι το πλήρες όνομα του, είναι ο μικρότερος αδελφός του Φιντέλ και Πρόεδρος της Κούβας από το 2008. Γεννημένος το 1931 στο Μπιράν της Κούβας, η ζωή και η δράση του βρέθηκε πάντα στη σκιά του θρυλικού αδελφού του. Ο Ραούλ υπήρξε ο λόγος της συνάντησης του Φιντέλ με τον Τσε Γκεβάρα στο Μεξικό, καθώς ήταν πρωτοβουλία του ιδίου να συστήσει τον νεαρό τότε αργεντίνο γιατρό στον αδελφό του. Καθόλη τη διάρκεια της επαναστατικής δραστηριότητας στην Κούβα ο Ραούλ υπήρξε σταθερά αρωγός και υποστηρικτής των προσπαθειών του Φιντέλ, κάτι που συνεχίστηκε μέχρι τη μεταβίβαση των εξουσιών στον ίδιο το 2008.

Ο Ραούλ Μοδέστο Κάστρο Ρούζ, όπως είναι το πλήρες όνομα του, είναι ο μικρότερος αδελφός του Φιντέλ και Πρόεδρος της Κούβας από το 2008. Γεννημένος το 1931 στο Μπιράν της Κούβας, η ζωή και η δράση του βρέθηκε πάντα στη σκιά του θρυλικού αδελφού του. Ο Ραούλ υπήρξε ο λόγος της συνάντησης του Φιντέλ με τον Τσε Γκεβάρα στο Μεξικό, καθώς ήταν πρωτοβουλία του ιδίου να συστήσει τον νεαρό τότε αργεντίνο γιατρό στον αδελφό του. Καθόλη τη διάρκεια της επαναστατικής δραστηριότητας στην Κούβα ο Ραούλ υπήρξε σταθερά αρωγός και υποστηρικτής των προσπαθειών του Φιντέλ, κάτι που συνεχίστηκε μέχρι τη μεταβίβαση των εξουσιών στον ίδιο το 2008. Ο Φουλχένσιο Μπατίστα (1901-1973) υπήρξε Κουβανός στρατηγός, Πρόεδρος και δικτάτορας έχοντας την υποστήριξη των Ηνωμένων Πολιτειών της Αμερικής. Υπήρξε ηγέτης της Κούβας κατά τα διαστήματα 1933-1944 και 1952-1959. Το 1959 ανατράπηκε ως αποτέλεσμα της επικράτησης της Κουβανικής Επανάστασης. Η δικτατορία του αποτέλεσε την αφορμή γιά τον Τσε ώστε να μεταβεί στην Κούβα προς υποστήριξη του επαναστατικού κινήματος.

Ο Φουλχένσιο Μπατίστα (1901-1973) υπήρξε Κουβανός στρατηγός, Πρόεδρος και δικτάτορας έχοντας την υποστήριξη των Ηνωμένων Πολιτειών της Αμερικής. Υπήρξε ηγέτης της Κούβας κατά τα διαστήματα 1933-1944 και 1952-1959. Το 1959 ανατράπηκε ως αποτέλεσμα της επικράτησης της Κουβανικής Επανάστασης. Η δικτατορία του αποτέλεσε την αφορμή γιά τον Τσε ώστε να μεταβεί στην Κούβα προς υποστήριξη του επαναστατικού κινήματος. The following speech was given by Fidel Castro on 8 October 1987 at the main ceremony marking the twentieth anniversary of Guevara’s death. It was held at a newly completed electronics components factory in the city of Pinar del Río.

The following speech was given by Fidel Castro on 8 October 1987 at the main ceremony marking the twentieth anniversary of Guevara’s death. It was held at a newly completed electronics components factory in the city of Pinar del Río.

Το Κομμουνιστικό Κόμμα της Κούβας (Partido Communista de Cuba) αποτελεί τη μετεξέλιξη της Επαναστατικής κυβέρνησης του Φιντέλ Κάστρο που ανέλαβε την εξουσία το 1959. Βασισμένο αρχές του μαρξισμού-λενινισμού, ιδρύθηκε στις 3 Οκτωβρίου 1965 στην Αβάνα. Πρώτος Γενικός Γραμματέας ορίστηκε τότε ο σημερινός πρόεδρος της χώρας, Ραούλ Κάστρο.

Το Κομμουνιστικό Κόμμα της Κούβας (Partido Communista de Cuba) αποτελεί τη μετεξέλιξη της Επαναστατικής κυβέρνησης του Φιντέλ Κάστρο που ανέλαβε την εξουσία το 1959. Βασισμένο αρχές του μαρξισμού-λενινισμού, ιδρύθηκε στις 3 Οκτωβρίου 1965 στην Αβάνα. Πρώτος Γενικός Γραμματέας ορίστηκε τότε ο σημερινός πρόεδρος της χώρας, Ραούλ Κάστρο. Το Οχυρό του Σαν Κάρλος δε λα Καμπάνια (Fortaleza de San Carlos de la Cabaña), γνωστό ως Λα Καμπάνια, είναι ένα σύμπλεγμα κάστρων του 18ου αιώνα και βρίσκεται στην ανατολική πλευρά του λιμανιού της Αβάνας. Θεωρείται το μεγαλύτερο σε όλην την αμερικανική ήπειρο.

Το Οχυρό του Σαν Κάρλος δε λα Καμπάνια (Fortaleza de San Carlos de la Cabaña), γνωστό ως Λα Καμπάνια, είναι ένα σύμπλεγμα κάστρων του 18ου αιώνα και βρίσκεται στην ανατολική πλευρά του λιμανιού της Αβάνας. Θεωρείται το μεγαλύτερο σε όλην την αμερικανική ήπειρο. Thus, I remember that during the days of Batista’s final offensive in the Sierra Maestra mountains against our militant but small forces, the most experienced cadres were not in the front lines; they were assigned strategic leadership assignments and save for our devastating counterattack. It would have been pointless to put Che, Camilo [Cienfuegos], and other compañeros who had participated in many battles at the head of a squad. We held them back so that they could subsequently lead columns that would undertake risky missions of great importance, it was then that we did send them in enemy territory with full responsibility and awareness of the risks as in the case of the invasion of Las Villas led by Camilo and Che, an extraordinarily difficult assignment that required men of great experience and authority as column commanders, men capable of reaching the goal.

Thus, I remember that during the days of Batista’s final offensive in the Sierra Maestra mountains against our militant but small forces, the most experienced cadres were not in the front lines; they were assigned strategic leadership assignments and save for our devastating counterattack. It would have been pointless to put Che, Camilo [Cienfuegos], and other compañeros who had participated in many battles at the head of a squad. We held them back so that they could subsequently lead columns that would undertake risky missions of great importance, it was then that we did send them in enemy territory with full responsibility and awareness of the risks as in the case of the invasion of Las Villas led by Camilo and Che, an extraordinarily difficult assignment that required men of great experience and authority as column commanders, men capable of reaching the goal.