Κατηγορία: Ιστορικοί λόγοι

11 Δεκέμβρη 1964: Ο Τσε Γκεβάρα στα Ηνωμένα Έθνη (Ομιλία & Βίντεο)

Ήταν 11 Δεκέμβρη 1964 όταν ο Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα, εκπροσωπώντας την επαναστατική κυβέρνηση της Κούβας, μίλησε στη Γενική Συνέλευση του Οργανισμού των Ηνωμένων Εθνών.

Ήταν 11 Δεκέμβρη 1964 όταν ο Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα, εκπροσωπώντας την επαναστατική κυβέρνηση της Κούβας, μίλησε στη Γενική Συνέλευση του Οργανισμού των Ηνωμένων Εθνών.

Η ομιλία αυτή του Τσε, μνημείο αντι-ιμπεριαλιστικού λόγου και υπεράσπισης των λαών που μάχονται για την ελευθερία τους, έγινε χωρίς την παρουσία του εκπροσώπου των ΗΠΑ (Αντλάϊ Στίβενσον) στην αίθουσα της Γενικής Συνέλευσης. Άλλωστε είχαν προηγηθεί οι εχθρικές προσπάθειες της Ουάσινγκτον ενάντια στην Κούβα, η κρίση των πυραύλων, η απόβαση του Κόλπου των Χοίρων και η επιβολή του απάνθρωπου οικονομικού αποκλεισμού εκ μέρους της κυβέρνησης Κένεντι.

Ο Τσε, υπουργός βιομηχανίας τότε, ήταν ξεκάθαρος από την αρχή: “Η Κούβα προσέρχεται”, σημείωνε ο Γκεβάρα στην αρχή της ομιλίας του, “για να διευκρινήσει τη θέση της πάνω στα πιο σημαντικά απο τα επίμαχα θέματα (σημεία). Και θα το κάνει με όλη την συναίσθηση της ευθύνης που επιβάλλει η χρησιμοποίηση αυτού του βήματος. Ταυτόχρονα όμως θα ανταποκριθεί στο αναπότρεπτο καθήκον να μιλήσει με διαύγεια και ειλικρίνεια”.

Σε αυτές τις γραμμές αποτυπώνονταν οι πραγματικές προθέσεις της επαναστατικής κυβέρνησης της Κούβας – να καταγγείλει το διεθνή και αμερικανικό ιμπεριαλισμό, να στηρίξει δημόσια τους καταπιεσμένους λαούς και να παρακινήσει τα Ηνωμένα Έθνη να πάρουν θέση, να δράσουν προς όφελος της ειρήνης και της ελευθερίας. Όσο όμως σεβασμό απέδωσε ο Τσε στη Γενική Συνέλευση του ΟΗΕ, άλλο τόσο καυστικός ήταν απέναντι στην γνωστή τακτική του οργανισμού να “νίπτει τας χείρας του” μπροστά στα ιμπεριαλιστικά εγκλήματα. Σε μια αποστροφή του λόγου του κατήγγειλε την προσπάθεια του ιμπεριαλισμού να “μετατρέψει τη Γενική Συνέλευση σε άσκοπο διαγωνισμό ρητορικής”. Γι’ αυτο ο Γκεβάρα μπήκε στην ουσία της υπόθεσης.

Ντυμένος όχι με το τυπικό κοστούμι της διπλωματίας αλλά με την στρατιωτική του στολή, ο Τσε αναφέρθηκε στις προσπάθειες των Ηνωμένων Πολιτειών και των συμμάχων τους να δυναμιτίσουν τη διεθνή ειρήνη. Έκανε λόγο για την ανάγκη να υπάρξουν ειρηνικές σχέσεις όχι μόνο μεταξύ των ισχυρών κρατών, αλλά κυρίως μεταξύ των ισχυρών και των αδυνάτων, μεταξύ εθνών με διαφορετικό οικονομικο-πολιτικό σύστημα. Όχι όμως και μεταξύ εκμεταλλευτών και θυμάτων. Σε έναν καταιγισμό κατηγοριών κατά της επεμβατικής αμερικανικής εξωτερικής πολιτικής, ο Τσε Γκεβάρα χρησιμοποίησε πλήθος απτών παραδειγμάτων που επιβεβαίωναν στο ακέραιο τους ισχυρισμούς του: Από τις ιμπεριαλιστικές επεμβάσεις στη νοτιοανατολική Ασία (Καμπότζη, Λάος, Βιετνάμ) στην Κύπρο και από το αιματηρό παράδειγμα του Κονγκό στην ταλαιπωρημένη απ’ την επιθετικότητα της Ουάσινγκτον Λατινική Αμερική.

Από το βήμα του ΟΗΕ, ο Γκεβάρα έκανε σαφές το ζήτημα της αλληλεγγύης που πρέπει να διέπει το σοσιαλιστικό στρατόπεδο ενάντια στην απειλή του ιμπεριαλισμού-καπιταλισμού. Μιλώντας μέσα στο πλαίσιο της διπλωματικής ορολογίας αλλά χωρίς να αποκρύβει ούτε χιλιοστό της αλήθειας, ο Τσε παρέθεσε την ωμή παραβίαση της ειρήνης από την κυβέρνηση των ΗΠΑ. Κάτι που οι σοσιαλιστικές χώρες αλλά και όλοι οι λαοί που πολεμούν για την απελευθέρωση, την πολιτική και οικονομική χειραφέτηση τους δεν θα έπρεπε να δεχθούν με κανέναν τρόπο.

“Θέλουμε να οικοδομήσουμε τον σοσιαλισμό. Έχουμε κυρηχτεί αλληλέγγυοι μ’ εκείνους που αγωνίζονται για την ειρήνη, πήραμε θέση – μολονότι είμαστε μαρξιστές-λενινιστές – στο πλευρό των αδέσμευτων χωρών*, γιατί και οι αδέσμευτοι αγωνίζονται όπως και μεις ενάντια στον ιμπεριαλισμό. Θέλουμε την ειρήνη. Θέλουμε να δημιουργήσουμε μια καλύτερη ζωή για το λαό μας. Και γι’ αυτό το λόγο αποφεύγουμε, όσο μπορούμε, να απαντήσουμε στις προκλήσεις που μας κάνουν οι γιάνκηδες”.

“Θέλουμε να οικοδομήσουμε τον σοσιαλισμό. Έχουμε κυρηχτεί αλληλέγγυοι μ’ εκείνους που αγωνίζονται για την ειρήνη, πήραμε θέση – μολονότι είμαστε μαρξιστές-λενινιστές – στο πλευρό των αδέσμευτων χωρών*, γιατί και οι αδέσμευτοι αγωνίζονται όπως και μεις ενάντια στον ιμπεριαλισμό. Θέλουμε την ειρήνη. Θέλουμε να δημιουργήσουμε μια καλύτερη ζωή για το λαό μας. Και γι’ αυτό το λόγο αποφεύγουμε, όσο μπορούμε, να απαντήσουμε στις προκλήσεις που μας κάνουν οι γιάνκηδες”.

Μιλώντας εξ’ ονόματος του λαού και της κυβέρνησης της Κούβας, ο Τσε Γκεβάρα επισήμανε τις προσπάθειες της επαναστατικής κυβέρνησης του νησιού για ειρήνη στην ευρύτερη περιοχή της Καραϊβικής. Παρέθεσε ένα προς ένα πέντε σημεία που η Αβάνα είχε προτείνει στις ΗΠΑ ως μορατόριουμ για την δημιουργία κλίματος ειρήνης και ασφάλειας. Καμία πρόταση της Κούβας δεν έγινε αποδεχτή από τις ΗΠΑ, οι οποίες όχι μόνο συνέχισαν τις πολεμικές προκλήσεις ενάντια στον κουβανικό λαό αλλά και διατήρησαν (μέχρι και σήμερα) το στρατιωτικό ορμητήριο-φυλακή του Γκουαντάναμο.

Η ομιλία του Γκεβάρα όμως δεν εστιάστηκε μόνο στην ιμπεριαλιστική στρατηγική των ΗΠΑ, την ανάγκη για πυρηνικό αφοπλισμό, ούτε αποκλειστικά στην εκμετάλλευση των λαών της Λατινικής Αμερικής από το ξένο και ντόπιο Κεφάλαιο. Στην καρδιά του καπιταλισμού, στο κέντρο της Νέας Υόρκης, από του βήματος του ΟΗΕ, ο Γκεβάρα έστρεψε τα βέλη του προς το κοινωνικό απαρτχάιντ που επικρατούσε σε πολλές περιοχές των Ηνωμένων Πολιτειών. Ένα ρατσιστικό απαρτχάιντ που κατέτασε τους αφροαμερικανούς ως πολίτες ‘β κατηγορίας, στερούμενων βασικών πολιτικών και κοινωνικών δικαιωμάτων. Δήλωσε, ο Τσε, σε μια αποστροφή του λόγου του: “Οι ΗΠΑ επεμβαίνουν στην αμερικάνικη ήπειρο στο όνομα των ελευθέρων θεσμών. Θα ‘ρθει μια μέρα που τούτη η Συνέλευση θα έχει αποκτήσει μεγαλύτερη ωριμότητα και θα απαιτήσει τότε από τη βορειοαμερικάνικη κυβέρνηση εγγυήσεις για τη ζωή για τη ζωή του νέγρικου και του λατινοαμερικάνικου πληθυσμού, που ζει σ’αυτή τη χώρα και που στην πλειονότητα του είναι βορειοαμερικάνικος είτε λόγω καταγωγής είτε γιατί έκανε τις ΗΠΑ θετή πατρίδα του. Πως είναι δυνατό να παραστάνει το φρουρό της ελευθερίας εκείνος που σκοτώνει τα ίδια του τα παιδιά και καθημερινά τα ταπεινώνει για το χρώμα που έχει το δέρμα τους; Πως μπορεί να ποζάρει για φρουρός της ελευθερίας εκείνος που αφήνει ελεύθερους τους δολοφόνους των νέγρων και μάλιστα τους προστατεύει και τιμωρεί το νέγρικο πληθυσμό επειδή απαιτεί να γίνουν σεβαστά τα δικαιώματα του ως ελεύθερων ανθρώπων;”.

Εκεί, στην καρδιά του διεθνούς διπλωματικού συστήματος, ο αργεντίνος επανάστατης μίλησε και εκφράστηκε όχι μόνο εξ’ ονόματος της κουβανικούς κυβέρνησης που τυπικά εκπροσωπούσε. Εξέφρασε κυρίως τους καταφρονεμένους του κόσμου, τους λαούς που καταδυναστεύονταν από τις δυνάμεις του ιμπεριαλισμού και που αλληλοσφαγιάζονταν από εμφύλιες συγκρούσεις τις οποίες το μεγάλο κεφάλαιο είχε προκαλέσει στις χώρες τους. “Η Ιστορία”, είπε ο Γκεβάρα λίγο πριν το κλείσιμο της ομιλίας του, “θα υποχρεωθεί τώρα να πάρει υπ’ όψιν της τους φτωχούς της Αμερικής, τους καταληστεμένους και καταφρονεμένους που αποφάσισαν στο εξής να γράφουν μόνοι τους την ιστορία τους”.

(* Κίνημα των Αδεσμεύτων: Διακρατική οργάνωση χωρών που δεν επιθυμούσαν να τεθούν άμεσα με το μέρος κανενός εκ των δύο κυρίαρχων «στρατοπέδων» του Ψυχρού Πολέμου, δηλαδή ΗΠΑ και ΕΣΣΔ. Ιδρύθηκε το 1961 στο Βελιγράδι).

Δύο απόπειρες δολοφονίας.

Η παρουσία του Κομαντάντε Γκεβάρα στη Νέα Υόρκη είχε προκαλέσει την αντίδραση κουβανικών αντεπαναστατικών δυνάμεων. Δύο τρομοκρατικές ενέργειες, με προφανή σκοπό τη δολοφονία του Τσε, έλαβαν χώρα την 11η Δεκέμβρη 1964 στο Μανχάταν της αμερικανικής μεγαλούπολης. Η πρώτη ήταν η εκτόξευση ρουκέτας από μπαζούκας προς το κτίριο των Ηνωμένων Εθνών την ώρα που ο Γκεβάρα ήταν στο βήμα της Γενικής Συνέλευσης. Σύμφωνα με τις τοπικές αρχές, το βλήμα είχε εκτοξευθεί από την περιοχή Κουϊνς της ανατολικής όχθης και έπεσε στη θάλασσα, 200 περίπου μέτρα πριν τις ακτές του Μανχάταν. Ποτέ δεν διευκρινίστηκε ποιός εκτόξευσε τη ρουκέτα από το μπαζούκας που, σύμφωνα με τις έρευνες της αστυνομίας, ήταν ιδιοκτησίας του στρατού των ΗΠΑ.

Την ίδια ώρα που στην αίθουσα της Γενικής Συνέλευσης ο Τσε Γκεβάρα κατηγορούσε τον αμερικάνικο και διεθνή ιμπεριαλισμό, στην είσοδο του κτιρίου του ΟΗΕ ομάδες αντεπαναστατών, κουβανών και αμερικανών, διαδήλωναν με πλακάτ και σημαίες. Η αστυνομία της Νέας Υόρκης είχε συλλάβει μάλιστα μια ισπανόφωνη γυναίκα, ονόματι Μόλι Γκονζάλες, η οποία κατευθύνονταν προς το κτίριο του ΟΗΕ κρατώντας μαχαίρι. Σκοπός της, όπως η ίδια δήλωσε αργότερα, ήταν να χτυπήσει τον Γκεβάρα όταν αυτός θα έβγαινε απ’ την είσοδο του κτιριακού συγκροτήματος.

Ολόκληρη η ομιλία του Τσε στη Γ.Σ. του ΟΗΕ και η δευτερολογία του-απάντηση στις αιτιάσεις των πρέσβεων λατινοαμερικάνικων χωρών. [PDF]

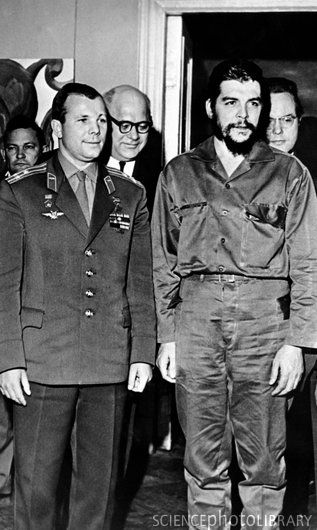

Φωτογραφικό υλικό από την παρουσία του Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα στη Γενική Συνέλευση του Οργανισμού Ηνωμένων Εθνών.

Cuba: Historical exception or vanguard in the anticolonial struggle?

Speech by Ernesto Che Guevara delivered on April 9, 1961.

«The working class is the creative class; the working class produces what material wealth exists in a country. And while power is not in their hands, while the working class allows power to remain in the hands of the bosses who exploit them, in the hands of landlords, the speculators, the monopolies and in the hands of foreign and national interest groups, while armaments are in the hands of those in the service of these interest groups and not in their own hands, the working class will be forced to lead a miserable existence no matter how many crumbs those interest groups should let fall from their banquet table.»

— Fidel Castro

Never in the Americas has an event of such extraordinary character, with such deep roots and such far-reaching consequences for the destiny of the continent’s progressive movements taken place as our revolutionary war. This is true to such an extent that it has been appraised by some to be the decisive event of the Americas, on a scale of importance second only to that great trilogy — the Russian Revolution, the victory over Nazi Germany and the subsequent social transformations and the victory of the Chinese Revolution.

Never in the Americas has an event of such extraordinary character, with such deep roots and such far-reaching consequences for the destiny of the continent’s progressive movements taken place as our revolutionary war. This is true to such an extent that it has been appraised by some to be the decisive event of the Americas, on a scale of importance second only to that great trilogy — the Russian Revolution, the victory over Nazi Germany and the subsequent social transformations and the victory of the Chinese Revolution.

Our revolution, unorthodox in its forms and manifestations, has nevertheless followed the general lines of all the great historical events of this century that are characterized by anticolonial struggles and the transition toward socialism.

Nevertheless some sectors, whether out of self-interest or in good faith, claim to see in the Cuban Revolution exceptional origins and features whose importance for this great historical-social event they inflate even to the level of decisive factors. They speak of the exceptionalism of the Cuban Revolution as compared with the course of other progressive parties in Latin America. They conclude that the form and road of the Cuban Revolution are unique and that in the other countries of the Americas the historical transition will be different.

We accept that exceptions exist which give the Cuban Revolution its peculiar characteristics. It is clearly established that in every revolution there are specific factors, but it is no less established that all follow laws that society cannot violate. Let us analyze, then, the factors of this purported exceptionalism.

The first, and perhaps the most important and original, is that cosmic force called Fidel Castro Ruz, whose name in only a few years has attained historic proportions. The future will provide the definitive appraisal of our prime minister’s merits, but to us they appear comparable to those of the great historic figures of Latin America. What is exceptional about Fidel Castro’s personality? Various features of his life and character make him stand out far above his compañeros and followers. Fidel is a person of such tremendous personality that he would attain leadership in whatever movement he participated. It has been like that throughout his career, from his student days to the premiership of our country and as a spokesperson for the oppressed peoples of the Americas. He has the qualities of a great leader, added to which are his personal gifts of audacity, strength, courage, and an extraordinary determination always to discern the will of the people — and these have brought him the position of honor and sacrifice that he occupies today. But he has other important qualities — his ability to assimilate knowledge and experience in order to understand a situation in its entirety without losing sight of the details, his unbounded faith in the future, and the breadth of his vision to foresee events and anticipate them in action, always seeing farther and more accurately than his compañeros . With these great cardinal qualities, his capacity to unite, resisting the divisions that weaken; his ability to lead the whole people in action; his infinite love for the people; his faith in the future and with his capacity to foresee it, Fidel Castro has done more than anyone else in Cuba to create from nothing the present formidable apparatus of the Cuban Revolution.

No-one, however, could assert that specific political and social conditions existed in Cuba that were totally different from those in the other countries of the Americas, or that precisely because of those differences the revolution took place. Neither could anyone assert, conversely, that Fidel Castro made the revolution despite a lack of difference. Fidel, a great and able leader, led the revolution in Cuba, at the time and in the way he did, by interpreting the profound political disturbances that were preparing the people for their great leap onto the revolutionary road. Certain conditions were not unique to Cuba but it will be hard for other peoples to take advantage of them because imperialism — in contrast to some progressive groups — does learn from its errors. The condition we would describe as exceptional was the fact that U.S. imperialism was disoriented and was never able to accurately assess the true scope of the Cuban Revolution. This partly explains the many apparent contradictions in U.S. policy.

The monopolies, as is habitual in such cases, began to think of a successor for Batista precisely because they knew that the people were opposed to him and were looking for a revolutionary solution. What more intelligent and expert stroke than to depose the now unserviceable little dictator and to replace him with the new “boys” who would in turn serve the interests of imperialism? The empire gambled for a time on this card from its continental deck, and lost miserably.

Prior to our military victory they were suspicious of us, but not afraid. Actually, with all their experience at this game they were so accustomed to winning, they played with two decks. On various occasions emissaries of the U.S. State Department came, disguised as reporters, to investigate our rustic revolution, yet they never found any trace of imminent danger. By the time the imperialists wanted to react — when they discovered that the group of inexperienced young men marching in triumph through the streets of Havana had a clear awareness of their political duty and an iron determination to carry out that duty — it was already too late. Thus, in January 1959, the first social revolution in the Caribbean and the most profound of the Latin American revolutions dawned.

It could not be considered exceptional that the bourgeoisie, or at least a part of it, favored the revolutionary war over the dictatorship at the same time as it supported and promoted movements seeking negotiated solutions that would permit them to substitute elements disposed to curb the revolution for the Batista regime. Considering the conditions in which the revolutionary war took place and the complexity of the political tendencies that opposed the dictatorship, it was not at all exceptional that some elements adopted a neutral, or at least a nonbelligerent, attitude toward the insurrectionary forces. It is understandable that the national bourgeoisie, choked by imperialism and the dictatorship — whose troops sacked small properties and made extortion a daily way of life — felt a certain sympathy when they saw those young rebels from the mountains punish the mercenary army, the military arm of imperialism.

Nonrevolutionary forces did indeed aid the coming of revolutionary power.

A further exceptional factor was that in most of Cuba the peasants had been progressively proletarianized due to the needs of large-scale, semimechanized capitalist agriculture. They had reached a new level of organization and therefore a greater class consciousness. In mentioning this we should also point out, in the interest of truth, that the first area in which the Rebel Army operated (comprising the survivors of the defeated column who had made the Granma voyage) was an area inhabited by peasants whose social and cultural roots were different from those of the peasants found in the areas of large-scale, semimechanized Cuban agriculture. In fact the Sierra Maestra, the site of the first revolutionary settlement, is a place where peasants who had struggled against large landholders took refuge. They went there seeking new land — somehow overlooked by the state or the voracious landholders — on which to earn a modest income. They struggled constantly against the demands of the soldiers, always allied to the landholders, and their ambitions extended no further than a property deed. The peasants who belonged to our first guerrilla armies came from that section of this social class which most strongly shows love for the land and the possession of it; that is to say, which most perfectly demonstrates the petty-bourgeois spirit. The peasants fought because they wanted land for themselves and their children, to manage and sell it and to enrich themselves through their labor.

Despite their petty-bourgeois spirit, the peasants soon learned that they could not satisfy their desire to possess land without breaking up the large landholding system. Radical agrarian reform, the only type that could give land to the peasants, clashed directly with the interests of the imperialists, the large landholders and the sugar and cattle magnates. The bourgeoisie was afraid to clash with those interests but the proletariat was not. In this way the course of the revolution itself brought the workers and peasants together. The workers supported the demands of the peasants against the large landholders. The poor peasants, rewarded with ownership of land, loyally supported the revolutionary power and defended it against its imperialist and counterrevolutionary enemies.

In our opinion no further exceptionalism can be claimed. We have been generous to extend it this far. We shall now examine the permanent roots of all social phenomena in the Americas: the contradictions that mature in the wombs of present societies and produce changes that can reach the magnitude of a revolution such as Cuba’s.

First, in chronological order although not in order of importance at present, is the large landholding system. It was the economic power base of the ruling class throughout the entire period following the great anticolonial revolutions of the last century. The large landholding social class, found in all Latin American countries, generally lags behind the social developments that move the world. In some places, however, the most alert and clear sighted members of this class are aware of the dangers and begin to change the form of their capital investment , at times opting for mechanized agriculture, transferring some of their wealth to industrial investment or becoming commercial agents of the monopolies. In any case, the first liberating revolutions never destroyed the large landholding powers that always constituted a reactionary force and upheld the principle of servitude on the land.

This phenomenon, prevalent in all the countries of the Americas, has been the foundation of all the injustices committed since the era when the King of Spain gave huge grants of land to his most noble conquistadores. In the case of Cuba, only the unappropriated royal lands — the scraps left between where three circular landholdings met — were left for the natives, Creoles and mestizos.

In most countries the large landholders realized they couldn’t survive alone and promptly entered into alliances with the monopolies — the strongest and most ruthless oppressors of the Latin American peoples. U.S. capital arrived on the scene to exploit the virgin lands and later carried off, unnoticed, all the funds so “generously” given, plus several times the amount originally invested in the “beneficiary” country. The Americas were a field of interimperialist struggle. The “wars” between Costa Rica and Nicaragua, the separation of Panama from Colombia, the infamy committed against Ecuador in its dispute with Peru, the fight between Paraguay and Bolivia, are nothing but expressions of this gigantic battle between the world’s great monopolistic powers, a battle decided almost completely in favor of the U.S. monopolies following World War II. From that point on the empire dedicated itself to strengthening its grip on its colonial possessions and perfecting the whole structure to prevent the intrusion of old or new competitors from other imperialist countries. This resulted in a monstrously distorted economy which has been described by the shamefaced economists of the imperialist regime with an innocuous vocabulary revealing the deep compassion they feel for us inferior beings. They call our miserably exploited Indians, persecuted and reduced to utter wretchedness, “little Indians” and they call blacks and mulattos, disinherited and discriminated against, “colored” — all this as a means of dividing the working masses in their struggle for a better economic future. For all of us, the peoples of the Americas, they have a polite and refined term: “underdeveloped.” What is underdevelopment?

A dwarf with an enormous head and a swollen chest is “underdeveloped” inasmuch as his weak legs or short arms do not match the rest of his anatomy. He is the product of an abnormal formation distorting his development. In reality that is what we are — we, politely referred to as “underdeveloped,” in truth are colonial, semicolonial or dependent countries. We are countries whose economies have been distorted by imperialism, which has abnormally developed those branches of industry or agriculture needed to complement its complex economy. “Underdevelopment,” or distorted development, brings a dangerous specialization in raw materials, inherent in which is the threat of hunger for all our peoples. We, the “underdeveloped,” are also those with the single crop, the single product, the single market. A single product whose uncertain sale depends on a single market imposing and fixing conditions. That is the great formula for imperialist economic domination. It should be added to the old, but eternally youthful Roman formula: Divide and Conquer!

The system of large landholding, then, through its connections with imperialism, completely shapes so-called “underdevelopment,” resulting in low wages and unemployment that in turn create a vicious cycle producing ever lower wages and greater unemployment. The great contradictions of the system sharpen, constantly at the mercy of the cyclical fluctuations of its own economy, and provide the common denominator for all the peoples of America, from the Rio Bravo to the South Pole. This common denominator, which we shall capitalize and which serves as the starting point for analysis by all who think about these social phenomena, is called the People’s Hunger. The people are weary of being oppressed, persecuted, exploited to the maximum. They are weary of the wretched selling of their labor-power day after day — faced with the fear of joining the enormous mass of unemployed — so that the greatest profit can be wrung from each human body, profit later squandered in the orgies of the masters of capital. We see that there are great and inescapable common denominators in Latin America, and we cannot say we were exempt from any of those, leading to the most terrible and permanent of all: the people’s hunger.

Large landholding, whether in its primitive form of exploitation or as a form of capitalist monopoly, adjusts to the new conditions and becomes an ally of imperialism — that form of finance and monopoly capitalism which goes beyond national borders — in order to create economic colonialism, euphemistically called “underdevelopment,” resulting in low wages, underemployment and unemployment: the people’s hunger.

All this existed in Cuba. Here, too, there was hunger. Here, the proportion of unemployed was one of the highest in Latin America. Here, imperialism was more ruthless than in many countries of America. And here, large landholdings existed as much as they did in any other Latin American country.

What did we do to free ourselves from the vast imperialist system with its entourage of puppet rulers in each country, its mercenary armies to protect the puppets and the whole complex social system of the exploitation of human by human? We applied certain formulas, discoveries of our empirical medicine for the great ailments of our beloved Latin America, empirical medicine which rapidly became scientific truth.

Objective conditions for the struggle are provided by the people’s hunger, their reaction to that hunger, the terror unleashed to crush the people’s reaction and the wave of hatred that the repression creates. The rest of the Americas lacked the subjective conditions, the most important of which is consciousness of the possibility of victory against the imperialist powers and their internal allies through violent struggle. These conditions were created through armed struggle — which progressively clarified the need for change and permitted it to be foreseen — and through the defeat and subsequent annihilation of the army by the popular forces (an absolutely necessary condition for every genuine revolution ).

Having already demonstrated that these conditions are created through armed struggle, we have to explain once more that the scene of the struggle should be the countryside. A peasant army pursuing the great objectives for which the peasantry should fight (the first of which is the just distribution of land) will capture the cities from the countryside. The peasant class of Latin America, basing itself on the ideology of the working class whose great thinkers discovered the social laws governing us, will provide the great liberating army of the future — as it has already done in Cuba. This army, created in the countryside where the subjective conditions for the taking of power mature, proceeds to take the cities, uniting with the working class and enriching itself ideologically. It can and must defeat the oppressor army, at first in skirmishes, engagements and surprises and, finally, in big battles when the army will have grown from small-scale guerrilla footing to a great popular army of liberation. A vital stage in the consolidation of the revolutionary power, as we have said, will be the liquidation of the old army.

If these conditions present in Cuba existed in the rest of the Latin American countries, what would happen in other struggles for power by the dispossessed classes? Would it be feasible to take power or not? If it was feasible, would it be easier or more difficult than in Cuba? Let us mention the difficulties that in our view will make the new Latin American revolutionary struggles more difficult. There are general difficulties for every country and more specific difficulties for some whose level of development or national peculiarities are different. We mentioned at the beginning of this essay that we could consider the attitude of imperialism, disoriented in the face of the Cuban Revolution, as an exceptional factor. The attitude of the national bourgeoisie was, to a certain extent, also exceptional. They too were disoriented and even looked sympathetically upon the action of the rebels due to the pressure of the empire on their interests — a situation which is indeed common to all our countries.

Cuba has again drawn the line in the sand, and again we see Pizarro’s dilemma: On the one hand there are those who love the people and on the other, those who hate the people. The line between them divides the two great social forces, the bourgeoisie and the working class, each of which are defining, with increasing clarity, their respective positions as the process of the Cuban Revolution advances.

Imperialism has learned the lesson of Cuba well. It will not allow itself to be caught by surprise in any of our 20 republics or in any of the colonies that still exist in the Americas. This means that vast popular struggles against powerful invading armies await those who now attempt to violate the peace of the sepulchers, pax Romana. This is important because if the Cuban liberation war was difficult, with its two years of continuous struggle, anguish and instability, the new battles awaiting the people in other parts of Latin America will be infinitely more difficult.

The United States hastens the delivery of arms to the puppet governments they see as being increasingly threatened; it makes them sign pacts of dependence to legally facilitate the shipment of instruments of repression and death and of troops to use them. Moreover, it increases the military preparation of the repressive armies with the intention of making them efficient weapons against the people.

And what about the bourgeoisie? The national bourgeoisie generally is not capable of maintaining a consistent struggle against imperialism. It shows that it fears popular revolution even more than the oppression and despotic dominion of imperialism which crushes nationality, tarnishes patriotic sentiments, and colonizes the economy.

A large part of the bourgeoisie opposes revolution openly, and since the beginning has not hesitated to ally itself with imperialism and the landowners to fight against the people and close the road to revolution. A desperate and hysterical imperialism, ready to undertake any maneuver and to give arms and even troops to its puppets in order to annihilate any country which rises up; ruthless landowners, unscrupulous and experienced in the most brutal forms of repression; and, finally, a bourgeoisie willing to close, through any means, the roads leading to popular revolution: These are the great allied forces which directly oppose the new popular revolutions of Latin America.

Such are the difficulties that must be added to those arising from struggles of this kind under the new conditions found in Latin America following the consolidation of that irreversible phenomenon represented by the Cuban Revolution.

There are still other, more specific problems. It is more difficult to prepare guerrilla groups in those countries that have a concentrated population in large centers and a greater amount of light and medium industry, even though it may not be anything like effective industrialization. The ideological influence of the cities inhibits the guerrilla struggle by increasing the hopes for peacefully organized mass struggle. This gives rise to a certain “institutionalization,” which in more or less “normal” periods makes conditions less harsh than those usually inflicted on the people. The idea is even conceived of possible quantitative increases in the congressional ranks of revolutionary forces until a point is someday reached which allows a qualitative change.

There are still other, more specific problems. It is more difficult to prepare guerrilla groups in those countries that have a concentrated population in large centers and a greater amount of light and medium industry, even though it may not be anything like effective industrialization. The ideological influence of the cities inhibits the guerrilla struggle by increasing the hopes for peacefully organized mass struggle. This gives rise to a certain “institutionalization,” which in more or less “normal” periods makes conditions less harsh than those usually inflicted on the people. The idea is even conceived of possible quantitative increases in the congressional ranks of revolutionary forces until a point is someday reached which allows a qualitative change.

It is not probable that this hope will be realized given present conditions in any country of the Americas, although a possibility that the change can begin through the electoral process is not to be excluded. Current conditions, however, in all countries of Latin America make this possibility very remote. Revolutionaries cannot foresee all the tactical variables that may arise in the course of the struggle for their liberating program. The real capacity of a revolutionary is measured by their ability to find adequate revolutionary tactics in every different situation and by keeping all tactics in mind so that they might be exploited to the maximum. It would be an unpardonable error to underestimate the gain a revolutionary program could make through a given electoral process, just as it would be unpardonable to look only to elections and not to other forms of struggle, including armed struggle, to achieve power — the indispensable instrument for applying and developing a revolutionary program. If power is not achieved, all other conquests, however advanced they appear, are unstable, insufficient and incapable of producing necessary solutions.

When we speak of winning power via the electoral process, our question is always the same: If a popular movement takes over the government of a country by winning a wide popular vote and resolves as a consequence to initiate the great social transformations which make up the triumphant program, would it not immediately come into conflict with the reactionary classes of that country? Has the army not always been the repressive instrument of that class? If so, it is logical to suppose that this army will side with its class and enter the conflict against the newly constituted government. By means of a more or less bloodless coup d’état, this government can be overthrown and the old game renewed again, never seeming to end. It could also happen that an oppressor army could be defeated by an armed popular reaction in defense and support of its government. What appears difficult to believe is that the armed forces would accept profound social reforms with good grace and peacefully resign themselves to their liquidation as a caste.

Where there are large urban concentrations, even when economically backward, it may be advisable — in our humble opinion — to engage in struggle outside the limits of the city in a way that can continue for a long time. The existence of a guerrilla center in the mountains of a country with populous cities maintains a perpetual focus of rebellion because it is very improbable that the repressive powers will be able, either rapidly or over a long period of time, to liquidate guerrilla groups with established social bases in territory favorable to guerrilla warfare, if the strategy and tactics of this type of warfare are consistently employed.

What would happen in the cities is quite different. Armed struggle against the repressive army can develop to an unanticipated degree, but this struggle will become a frontal one only when there is a powerful army to fight against [the enemy] army. A frontal fight against a powerful and well equipped army cannot be undertaken by a small group.

For the frontal fight, many arms will be needed, and the question arises: Where are these arms to be found? They do not appear spontaneously; they must be seized from the enemy. But in order to seize them from the enemy, it is necessary to fight; and it is not possible to fight openly. The struggle in the big cities must therefore begin clandestinely, capturing military groups or weapons one by one in successive assaults. If this happens, a great advance can be made.

Still, we would not dare to say that victory would be denied to a popular rebellion with a guerrilla base inside the city. No one can object on theoretical grounds to this strategy; at least we have no intention of doing so. But we should point out how easy it would be as the result of a betrayal, or simply by means of continuous raids, to eliminate the leaders of the revolution. In contrast, if while employing all conceivable maneuvers in the city (such as organized sabotage and, above all, that effective form of action, urban guerrilla warfare) and if a base is also maintained in the countryside, the revolutionary political power, relatively safe from the contingencies of the war, will remain untouched even if the oppressor government defeats and annihilates all the popular forces in the city. The revolutionary political power should be relatively safe, but not outside the war, not giving directions from some other country or from distant places. It should be within its own country fighting. These considerations lead us to believe that even in countries where the cities are predominant, the central political focus of the struggle can develop in the countryside.

Returning to the example of relying on help from the military class in effecting the coup and supplying the weapons, there are two problems to analyze: First, supposing it was an organized nucleus and capable of independent decisions, if the military really joins with the popular forces to strike the blow, there would in such a case be a coup by one part of the army against another, probably leaving the structure of the military caste intact. The other problem, in which armies unite rapidly and spontaneously with popular forces, can occur only after the armies have been violently beaten by a powerful and persistent enemy, that is, in conditions of catastrophe for the constituted power. With an army defeated and its morale broken, this phenomenon can occur. For that, struggle is necessary; we always return to the question of how to carry on that struggle. The answer leads us toward developing guerrilla struggle in the countryside, on favorable ground and supported by struggle in the cities, always counting on the widest possible participation of the working masses and guided by the ideology of that class.

We have sufficiently analyzed the obstacles revolutionary movements in Latin America will encounter. It can now be asked whether or not there are favorable conditions for the preliminary stage, like, for example, those encountered by Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra. We believe that here, too, general conditions can facilitate these centers of rebellion and specific conditions in certain countries exist which are even more favorable. Two subjective factors are the most important consequences of the Cuban Revolution: the first is the possibility of victory, knowing that the capability exists to crown an enterprise like that of the group of idealistic Granma expeditionaries who successfully struggled for two years in the Sierra Maestra. This immediately indicates there can be a revolutionary movement operating from the countryside, mixing with the peasant masses, that will grow from weakness to strength, that will destroy the army in a frontal fight, that will capture cities from the countryside, that will strengthen through its struggle the subjective conditions necessary for seizing power. The importance of this fact is demonstrated in the huge number of “exceptionalists” who have recently appeared. “Exceptionalists” are those special beings who say they find in the Cuban Revolution a unique event which cannot be followed — led by someone who has few or no faults, who led the revolution through a unique path. We affirm this is completely false. Victory by the popular forces in Latin America is clearly possible in the form of guerrilla warfare undertaken by a peasant army in alliance with the workers, defeating the oppressor army in a frontal assault, taking cities by attack from the countryside, and dissolving the oppressor army — as the first stage in completely destroying the superstructure of the colonial world.

We should point out a second subjective factor: The masses not only know the possibility of triumph, they know their destiny. They know with increasing certainty that whatever the tribulations of history during short periods, the future belongs to the people; the future will bring about social justice. This knowledge will help raise revolutionary ferment to even greater heights than those prevailing in Latin America today.

Some less general factors do not appear with the same intensity from country to country. One very important one is the greater exploitation of the peasants in Latin America than there was in Cuba. Let us remind those who pretend to see the proletarianization of the peasantry in our insurrectionary stage, that we believe it was precisely this which accelerated the emergence of cooperatives as well as the achievement of power and the agrarian reform. This is in spite of the fact that the peasant of the first battles, the core of the Rebel Army, is the same one to be found today in the Sierra Maestra, proud owner of their parcel of land and intransigently individualistic.

There are, of course, characteristics specific to the Latin American countries: an Argentine peasant does not have the same outlook as a communal peasant in Peru, Bolivia or Ecuador. But hunger for land is permanently present in the peasants, and they generally hold the key to the Americas. In some countries they are even more exploited than they were in Cuba, increasing the possibility that this class will rise up in arms. Another fact is Batista’s army, which with all its enormous defects, was structured in such a way that everyone, from the lowest soldier to the highest general, was an accomplice in the exploitation of the people. They were complete mercenaries, and this gave the repressive apparatus some cohesiveness. The armies of Latin America generally include a professional officers’ corps and recruits who are called up periodically. Each year, young recruits leave their homes where they have known the daily sufferings of their parents, have seen them with their own eyes, where they have felt poverty and social injustice. If one day they are sent as cannon fodder to fight against the defenders of a doctrine they feel in their own hearts is just, their capacity to fight aggressively will be seriously affected. Adequate propaganda will enable the recruits to see the justice of and the reasons for the struggle, and magnificent results will be achieved.

After this brief study of the revolutionary struggle we can say that the Cuban Revolution had exceptional factors giving it its own peculiarities as well as factors which are common to all the countries of the Americas and which express the internal need for revolution. New conditions will make the flow of these revolutionary movements easier as they give the masses consciousness of their destiny and the certainty that it is possible. On the other hand, there are now obstacles making it harder for the armed masses to achieve power rapidly, such as imperialism’s close alliance with the bourgeoisie, enabling them to fight to the utmost against the popular forces. Dark days await Latin America. The latest declarations of those that rule the United States seem to indicate that dark days await the world: Lumumba, savagely assassinated, in the greatness of his martyrdom showed the tragic mistakes that cannot be committed. Once the antiimperialist struggle begins, we must constantly strike hard, where it hurts the most, never retreating, always marching forward, counterstriking against each aggression, always responding to each aggression with even stronger action by the masses. This is the way to victory. We will analyze on another occasion whether the Cuban Revolution, having taken power, followed these new revolutionary paths with its own exceptional characteristics or if, as in this analysis, while respecting the existence of certain special characteristics, it fundamentally followed a logic derived from laws intrinsic to the social process.

* The Che Reader, Ocean Press. Copyright: © 2005 Aleida March, Che Guevara Studies Center and Ocean Press. Editing: Nikos Mottas/Guevaristas.

Η Νεολαία πρέπει να βαδίζει στην πρωτοπορία

Το παρακάτω κείμενο αποτελεί ομιλία του Τσε κατά το κλείσιμο σεμιναρίου που είχε διοργανώσει η Ένωση Νέων Κομμουνιστών του Υπουργείου Βιομηχανίας με τίτλο «Η νεολαία και η Επανάσταση». Εκφωνήθηκε στις 9 Μάη 1964 στην Αβάνα.

Το παρακάτω κείμενο αποτελεί ομιλία του Τσε κατά το κλείσιμο σεμιναρίου που είχε διοργανώσει η Ένωση Νέων Κομμουνιστών του Υπουργείου Βιομηχανίας με τίτλο «Η νεολαία και η Επανάσταση». Εκφωνήθηκε στις 9 Μάη 1964 στην Αβάνα.

Αυτό το φορτίο το κουβαλά κανείς για αρκετό καιρό και είναι δύσκολο να αποκοπεί από την σκέψη των ανθρώπων από τη μία μέρα στην άλλη – ακόμα και όταν διακηρρύσσεται ο σοσιαλιστικός χαρακτήρας της επανάστασης. Μάλιστα, η διακήρυξη αυτή καθυστέρησε σε σχέση με το ίδιο το γεγονός, γιατί υπήρχε ήδη μια σοσιαλιστική επανάσταση αφού είχαμε αναλάβει τον έλεγχο των περισσότερων από τα βασικά μέσα παραγωγής. Από πολιτική άποψη όμως δεν συμβαδίζαμε πλήρως με όλες τις κατακτήσεις που σημείωνε η επανάσταση στον οικονομικό τομέα και σε ορισμένες πτυχές του ιδεολογικού τομέα.

Αυτή η ιδιαιτερότητα της επανάστασης μας επιβάλλει να είμαστε πολύ προσεκτικοί όταν πρόκειται να χαρακτηρίσουμε το κόμμα μας ως ηγεσία της εργατικής τάξης στο σύνολο της και ιδιαίτερα σε ότι έχει να κάνει με τις συγκεκριμένες σχέσεις που αναπτύσσει με καθεμία από αυτές τις διοικητικές δομές όπως ο στρατός, ο μηχανισμός ασφάλειας κλπ. Το κόμμα μας δεν διαθέτει ακόμη καταστατικό, ούτε καν είναι ακόμη οριστικά διαμορφωμένο. Η ερώτηση, λοιπόν, είναι: Γιατί δεν υπάρχει καταστατικό; Εμπειρία υπάρχει μεγάλη και μάλιστα εμπειρία που έχει σχεδόν πενήντα χρόνια πρακτικής εφαρμογής. Τι είναι αυτό που συμβαίνει άραγε; Υπάρχουν ορισμένα ερωτήματα σχετικά με αυτήν την εμπειρία στα οποία προσπαθούμε να απαντήσουμε, ερωτήματα όμως που δεν μπορούμε να απαντήσουμε με τρόπο αυθόρμητο ούτε και με μια ανάλυση επιφανειακή γιατί οι συνέπειες για το μέλλον της επανάστασης είναι καθοριστικές.

Στην Κούβα η ιδεολογία των προηγούμενων κυρίαρχων τάξεων επιβιώνει επειδή αντανακλάται στις συνειδήσεις των ατόμων, όπως περιέγραψα προηγούμενως. Είναι επίσης παρούσα γιατί εισάγεται διαρκώς από τις Ηνωμένες Πολιτείες – το κέντρο συντονισμού της διεθνούς αντίδρασης – οι οποίες εξάγουν συμμορίες, δολιοφθορείς και προπαγανδιστές κάθε λογής, και με τις αδιάκοπες εκπομπές τους ουσιαστικά έχουν πρόσβαση σε ολόκληρη την εθνική επικράτεια, με εξαίρεση την Αβάνα. Ο λαός της Κούβας βρίσκεται συνεπώς σε συνεχή επαφή με την ιδεολογία των ιμπεριαλιστών. Η ιδεολογία αυτή διαμορφώνεται κατάλληλα εντός της χώρας μέσω μηχανισμών προπαγάνδας επιστημονικά σχεδιασμένων ώστε να προβάλλουν την σκοτεινή πλευρά ενός συστήματος σαν το δικό μας, το οποίο αναγκαστικά θα έχει και σκοτεινές πλευρές. Αυτό συμβαίνει διότι βρισκόμαστε σε μια μεταβατική περίοδο και επειδή όσοι από εμάς έχουμε ηγηθεί της επανάστασης έως τώρα δεν είμαστε επαγγελματίες οικονομολόγοι και πολιτικοί, με πλούσια εμπειρία και ένα επιτελείο από πίσω απ’ τον καθένα μας.

Την ίδια στιγμή, προβάλλουν τις πιο εκθαμβωτικές και φετιχιστικές όψεις του καπιταλιστικού συστήματος. Όλα αυτά εισάγονται στη χώρα και συχνά επιδρούν στο υποσυνείδητο πολλών ανθρώπων. Φέρνουν επίσης στην επιφάνεια απωθημένα συναισθήματα που δεν είχαν καν αγγιχτεί λόγω της ταχύτητας της διαδικασίας και της μεγάλης συναισθηματικής φόρτισης η οποία απαιτήθηκε για να υπερασπιστούμε την επανάσταση μας – όπου η λέξη «επανάσταση» συνδέθηκε με τη λέξη «πατρίδα», με την υπεράσπιση όλων των συμφερόντων μας. Αυτό είναι ότι ιερότερο για τον καθέναν, ανεξάρτητα ακόμα και από την ταξική του προέλευση.

Απέναντι στην απειλή μιας θερμοπυρηνικής επίθεσης, όπως τον Οκτώβρη (του 1962), η συσπείρωση του λαού ήταν αυτόματη. Πολλοί άνθρωποι που ούτε σκοπία δεν είχαν εμφανιστεί για να φυλάξουν ποτέ τους στις πολιτοφυλακές προσφέρθηκαν να πολεμήσουν. Συντελέστηκε μια μεταμόρφωση κάθε ανθρώπου μπροστά στην κατάφωρη αδικία. Καθένας ήθελε να εκδηλώσει την αποφασιστικότητα του να αγωνιστεί για την πατρίδα του. Και είχα να κάνει επίσης με την απόφαση που παίρνει ένας άνθρωπος όταν βρίσκεται μπροστά σε έναν κίνδυνο από τον οποίον δε μπορεί να ξεφύγει με κανέναν τρόπο τηρώντας ουδέτερη στάση – γιατί απέναντι στις ατομικές βόμβες δεν υπάρχει ουδετερότητα, ούτε πρεσβείες, ούτε τίποτα. Τα εξολοθρεύουν όλα.

Έτσι έχουμε πορευτεί: με άλματα, άλματα ακανόνιστα, όπως προχωρούν όλες οι επαναστάσεις, εμβαθύνοντας όμως την ιδεολογία μας συγκεκριμένους τομείς, μαθαίνοντας όλο και πιο πολύ, συγκροτώντας σχολές μαρξισμού. Ταυτόχρονα, ανησυχούμε διαρκώς μήπως, μέσα από αυτήν την κριτική στάση απέναντι στα καθήκοντα του κόμματος σε κάθε επίπεδο του κρατικού μηχανισμού, οδηγηθούμε σε στάσεις που θα αδρανοποιήσουν την επανάσταση και θα εισαγάγουν συγκαλλυμένα τις μικροαστικές αντιλήψεις ή την ιδεολογία του ιμπεριαλισμού. Γι’ αυτό ακόμη και σήμερα δεν έχουμε οργανώσει κατάλληλα το κόμμα – γι’ αυτό δεν έχουμε ακόμη εξασφαλίσει τον αναγκαίο βαθμό θεσμοποίησης στα ανώτερα επίπεδα του κράτους.

Μας απασχολούν, όμως, και ορισμένα άλλα ζητήματα. Πρέπει να οικοδομήσουμε κάτι καινούργιο που να μπορεί να εκφράζει με σαφήνεια τις σχέσεις που, κατά την κρίς μας, πρέπε να υπάρχουν ανάμεσα στις μάζες και στα άτομα που βρίσκονται σε θέσεις εξουσίας, τόσο άμεσα όσο και μέσω του κόμματος. Έχουν αρχίσει να εφαρμόζονται πιλοτικά διάφορα μοντέλα τοπικής αυτοδιοίκησης: ένα από αυτά βρίσκεται στο Ελ Κάνο, άλλο στο Γκουίνες και ένα άλλο στο Ματάνζας. Μέσα από αυτά τα πιλοτικά προγράμματα, παρατηρούμε διαρκώς τα πλεονεκτήματα και τα μειονεκτήματα όλων αυτών των διαφορετικών συστημάτων – στα οποία ενυπάρχουν σπέρματα ενός ανώτερου τύπου οργάνωσης – και ότι αντιπροσωπεύουν για την ανάπτυξη της επανάστασης και, κυρίως, για την ανάπτυξη του κεντρικού σχεδιασμού.

Μέσα σε αυτήν την πανσπερμία, μέσα από τις ιδεολογικές αντιπαραθέσεις υποστηρικτών διαφορετικών ιδεών, ακόμη και αν δεν υπήρχαν τάσεις ή καθορισμένα ρεύματα, άρχισε να αναπτύσσεται και το έργο της νεολαίας. Η οργάνωση νεολαίας άρχισε να λειτουργεί αρχικά ως παρακλάδι του Αντάρτικου Στρατού, κατέκτησε ένα μεγαλύτερο ιδεολογικό βάθος στην συνέχεια, και τέλος, εξελίχθηκε στην Ένωση Νέων Κομμουνιστών – σε έναν προθάλαμο θα λέγαμε για να γίνει κανείς μέλος του κόμματος, πράγμα το οποίο προϋποθέτει την υποχρέωση να αποκτήσει μια ανώτερη ιδεολογική κατάρτηση. Γύρω από αυτά τα ζητήματα δεν έγινε καμία πραγματική συζήτηση, αν και υπήρξαν κάποιες συζητήσεις σχετικά με το ποιος θα πρέπει να είναι ο ρόλος της οργάνωσης νεολαίας από πρακτική άποψη. Θα πρέπει η νεολαία να συναντιέται τρεις, τέσσερις ή πέντε ώρες για να συζητά φιλοσοφικά ζητήματα; Μπορεί να το κάνει, κανείς δεν λέει ότι δεν επιτρέπεται. Είναι απλώς ένα θέμα ισορροπίας και στάσης απέναντι στην επανάσταση, το κόμμα και κυρίως απέναντι στο λαό. Το γεγονός ότι η νεολαία καταπιάνεται με θεωρητικά ζητήματα δείχνει ότι έχει κατακτήσει ένα θεωρητικό βάθος. Όταν όμως το μόνο που κάνει είναι να ασχολείται με θεωρητικά ζητήματα, σημαίνει ότι η νεολαία δεν έχει καταφέρει να ξεπεράσει τη μηχανιστική αντιμετώπιση των πραγμάτων και βρίσκεται σε σύγχυση όσον αφορά τους στόχους της.

Έχει γίνει επίσης λόγος για τον αναγκαίο αυθορμητισμό, για τη χαρά της νιότης. Η νεολαία λοιπόν – αναφέρομαι στο σύνολο τα ης και όχι συγκεκριμένα σε αυτήν την ομάδα του Υπουργείου – οργάνωσε τη χαρά. Και οι ηγέτες της βάλθηκαν να αναλογίζονται τι είναι αυτό που οφείλουν να κάνουν οι νέοι, οι οποίοι εξ ορισμού θα πρέπει να είναι χαρούμενοι. Και αυτό ακριβώς μετέτρεπε τους νέους σε γέρους. Γιατί θα πρέπει ένας νέος άνθρωπος να κάτσει να σκεφτεί πως έπρεπε να είναι η νεολαία; Να κάνει απλά αυτό που σκέπτεται, αυτό θα πρέπει να χαρακτηρίζει τη νεολαία. Όμως συνέβαινε το αντίθετο, γιατί υπήρχε μια μερίδα ηγετών της νεολαίας που ήταν πραγματικά γερασμένη. Τότε είναι που η χαρά και ο αυθορμητισμός της νεολαίας γίνονται κάτι επιφάνειακό. Θα πρέπει για μια ακόμα φορά να είμαστε προσεκτικοί σε αυτό το ζήτημα και να μην συγχέουμε τη χαρά, τη ζωντάνια και τον αυθορμητισμό που διακρίνει τη νεολαία όλου του κόσμου – και κυρίως την κουβανική, λόγω των χαρακτηριστικών του κουβανικού λαού – με την επιπολαιότητα.

Πρόκειται για δύο εντελώς διαφορετικά πράγματα. Μπορεί κανείς και πρέπει να είναι αυθόρμητος και χαρούμενο, πρέπει όμως την ίδια στιγμή να είναι και σοβαρός. Τίθεται λοιπόν εδώ ένα από τα πλέον δυσεπίλυτα προβλήματα, ως προς την θεωρητική του διάσταση. Γιατί, με απλά λόγια, αυτό σημαίνει να είναι κανείς Νέος Κομμουνιστής. Δεν πρέπει να χρειάζεται να σκεφτείς πως θα πρέπει να είσαι, είναι κάτι που πρέπει να βγαίνει από μέσα σου.

Δεν ξέρω αν εισχωρώ σε βαθιά ημι-φιλοσοφικά νερά, αναφέρομαι όμως σε ένα από τα θέματα που μας έχουν απασχολήσει περισσότερο απ’ όλα. Ο κύριος τρόπος με τον οποίο η νεολαία θα πρέπει να δείχνει τον δρόμο προς τα εμπρός είναι ακριβώς με το να βρίσκεται στην πρωτοπορία σε καθέναν από τους τομείς εργασίας που συμμετέχει. Αυτός είναι ο λόγος που πολλές φορές είχαμε διάφορα μικροπροβλήματα με τη νεολαία: γιατί δεν έκοβε όσο ζαχαροκάλαμο όφειλε να κόψει, γιατί δεν συμμετείχε αρκετά στις εθελοντικές εργασίες. Με δυο λόγια, κανείς δεν μπορεί να καθοδηγήσει με τη θεωρία και μόνο, ούτε μπορεί να υπάρξει σταρτός αποτελούμενος από στρατηγούς. Ο στρατός μπορεί να έχει έναν στρατηγό, και αν είναι πολύ μεγάλος, μπορεί να έχει περισσότερους στρατηγούς και έναν γενικό διοικητή. Αν όμως δεν υπάρχουν αυτοί που θα πάνε στο πεδίο της μάχης, δεν υπάρχει στρατός. Και αν στο πεδίο της μάχης ο στρατός δεν καθοδηγείται από εκείνους που έχουν πάει και οι ίδιοι στο μέτωπο για να πολεμήσουν, αυτός ο στρατός είναι άχρηστος. Ένα από τα χαρακτηριστικά του δικού μας αντάρτικου στρατού ήταν ότι εκείνοι που προάγονταν σε έναν από τους τρείς και μοναδικούς βαθμούς του στρατού – υπολοχαγός, λοχαγός ή διοικητής – ήταν μόνο όσο είχαν με κάποιον τρόπο διακριθεί στο πεδίο της μάχης χάρη στις ατομικές τους αρετές.

Στους δύο πρώτους βαθμούς – του υπολοχαγού και του λοχαγού – ανήκαν όσοι διηύθυναν τις επιχειρήσεις των μαχών. Έχουμε ανάγκη συνεπώς από υπολοχαγούς και λοχαγούς ή όπως αλλιώς θέλετε να τους ονομάσουμε. Θα μπορούσαμε αν θέλετε να τους αφαιρέσουμε τον στρατιωτικό τίτλο. Τα άτομα, όμως, που θα βρίσκονται στην ηγεσία πρέπει να ηγούνται με τα ο παράδειγμα που δίνουν. Το να ακολουθήσεις κάποιον ή να κάνεις τους άλλους να σε ακολουθήσουν είναι ένα έργο που ορισμένες φορές μπορεί να γίνει δύσκολο. Είναι όμως απείρως πιο εύκολο από το να υποχρεώσεις κάποιους άλλους να βαδίσουν σε ένα μονοπάτι ανεξερεύνητο όπου κανείς δεν έχει ακόμη περπατήσει.

Η νεολαία μένει να αναλάβει τα μεγάλα ζητήματα που έχει προτάξει η κυβέρνηση, ως ζητήματα που πρέπει να αντιμετωπιστούν από τις λαϊκές μάζες, να τα μετατρέψει σε δική της υπόθεση και στον δρόμο αυτό να πορευτεί στην πρωτοπορία. Με την καθοδήγηση και τον προσανατολισμό του κόμματος, η νεολαία θα πρέπει να βαδίζει στην πρωτοπορία.

Με την απόρριψη όλων των λανθασμένων τρόπων λειτουργίας της ηγεσίας και την εκλογή ως μελών του κόμματος των παραδειγματικών εργαζομένων, των πρωτοπόρων εργαζομένων οι οποίοι στον χώρο εργασίας μπορούσαν να μιλήσουν με κύρος, των ίδιων πρωτοπόρων εργαζομένων που πήγαιναν στο μέτωπο, συντελείται η πρώτη ποιοτική αλλαγή στο κόμμα μας. [Σημ: Ως μέρος της αναδιοργάνωσης των Ενοποιημένων Επαναστατικών Οργανώσεων και της συγκρότησης τα ου Ενωμένου Κόμματος της Σοσιαλιστικής Επανάστασης, το 1962-1963, καθιερώθηκε μια διαδικασία κατά την οποία οι εργαζόμενοι εκλέγονται από τους συναδέλφους τους, σε συνελεύσεις που πραγματοποιούνται στους χώρους εργασίας, για την ομάδα από την οποία το κόμμα εκλέγει τα μέλη του. Αυτή η διαδικασία ισχύει μέχρι σήμερα στο Κομουνιστικό Κόμμα Κούβας].

Η αλλαγή αυτή, χωρίς να είναι η μοναδική, και συνοδευόμενη στην συνέχεια από μια σειρά οργανωτικών μέτρων, αποτελεί την πιο σημαντική πτυχή της μετεξέλιξης μας. Έχει επίσης υπάρξει μια σειρά αλλαγών όσον αφορά τη νεολαία.

Η δική μου τώρα επιμονή σε αυτό το σημείο – κάτι που κατ’ επανάληψη σας έχω εκφράσει – είναι να μην πάψετε να είστε νέοι, να μην μετατραπείται σε γέρους θεωρητικούς ή σε θεωρητικολόγους. Να διατηρήσετε τη φρεσκάδα και τον ενθουσιασμό της νιότης. Να είστε ικανοί να αφουγκράζεστε τα μεγάλα κελεύσματα της κυβέρνησης, να τα αφομοιώνετε και να γίνεστε η κινητήρια δύναμη ολόκληρου του μαζικού κινήματος, βαδίζοντας στην πρωτοπορία. Για να γίνει αυτό, θα πρέπει να μπορείτε να κρίνετε ποιοι είναι οι σημαντικοί τομείς στους οποίους η κυβέρνησης δίνει μεγαλύτερη έμφαση – μια κυβέρνηση που εκπροσωπεί το λαό και είναι την ίδια στιγμή ένα κόμμα.

Ταυτόχρονα, θα πρέπει κανείς να αξιολογεί τα πράγματα και να θέτει προτεραιότητες. Αυτά είναι τα καθήκοντα που πρέπει να εκπληρώσει η οργάνωση νεολαίας. Μιλήσατε για την τεχνολογική επανάσταση. Είναι ένα από τα πιο σημαντικά πράγματα, ένας από τους πιο συγκεκριμένους στόχους που προσιδιάζει στην ιδιοσυγκρασία των νέων. Δεν μπορεί όμως κανείς να πραγματοποιήσει την τεχνολογική επανάσταση από μόνος του, μια που είναι κάτι που συντελείται σε όλο τον κόσμο, σε κάθε χώρα, σοσιαλιστική και μη σοσιαλιστική – αναφέρομαι στις ανεπτυγμένες χωρες φυσικά.

Ταυτόχρονα, θα πρέπει κανείς να αξιολογεί τα πράγματα και να θέτει προτεραιότητες. Αυτά είναι τα καθήκοντα που πρέπει να εκπληρώσει η οργάνωση νεολαίας. Μιλήσατε για την τεχνολογική επανάσταση. Είναι ένα από τα πιο σημαντικά πράγματα, ένας από τους πιο συγκεκριμένους στόχους που προσιδιάζει στην ιδιοσυγκρασία των νέων. Δεν μπορεί όμως κανείς να πραγματοποιήσει την τεχνολογική επανάσταση από μόνος του, μια που είναι κάτι που συντελείται σε όλο τον κόσμο, σε κάθε χώρα, σοσιαλιστική και μη σοσιαλιστική – αναφέρομαι στις ανεπτυγμένες χωρες φυσικά.

Στις Ηνωμένες Πολιτείες συντελείται μια τεχνολογική επανάσταση. Στη Γαλλία υπάρχει μια ισχυρή τεχνολογική επανάσταση, όπως και στη Βρετανία και την Ομοσπονδιακή Δημοκρατία της Γερμανίας. Και οι χώρες αυτές σίγουρα δεν είναι σοσιαλιστικές. Η τεχνολογική επανάσταση πρέπει συνεπώς να έχει ένα ταξικό και σοσιαλιστικό περιεχόμενο. Για να υπάρξει αυτό, απαιτείται μια μεταμόρφωση της νεολαίας, ώστε να γίνει μια πραγματική κινητήριος δύναμη. Είναι απαραίτητο να εξαλειφθούν, με άλλα λόγια, όλα τα κατάλοιπα της παλιάς κοινωνίας που έχει πεθάνει. Δεν μπορούμε να δούμε την τεχνολογική επανάσταση ανεξάρτητα από μια κομμουνιστική στάση απέναντι στην εργασία. Αυτό είναι ιδιαίτερα σημαντικό. Αν δεν υπάρχει μια κομμουνιστική στάση απέναντι στην εργασία, δεν μπορεί να γίνει λόγος για μια σοσιαλιστική τεχνολογική επανάσταση.

Πρόκειται απλά για τον αντικατοπτρισμό στο εσωτερικό της Κούβας της τεχνολογοικής επανάστασης που συντελείται με μεγάλα βήματα χάρη στις πρόσφατες επιστημονικές εφευρέσεις και ανακαλύψεις. Αυτά είναι γεγονότα που δεν μπορούν να διαχωριστούν το ένα από το άλλο. Η κομμουνιστική στάση απέναντι στην εργασία συνίσταται στις αλλαγές που πραγματοποιούνται στην συνείδηση του κάθε ατόμου, αλλαγές που αναγκαστικά απαιτούν πολύ χρόνο. Δεν μπορεί κανείς να έχει την αξίωση οι αλλαγές αυτές να ολοκληρωθούν σε μια σύντομη χρονική περίοδο, κατά την οποία η εργασία θα εξακολουθεί να έχει τον ίδιο χαρακτήρα που έχει και σήμερα – θα εξακολουθεί να είναι μια καταναγκαστική κοινωνική υποχρέωση – ώσπου να μετατραπεί σε κοινωνική ανάγκη. Αν σε κάθε μας βήμα συνδιάζουμε την ικανότητα να μεταμορφώνουμε τους εαυτούς μας, γενικεύοντας την στάση μας απέναντι στη μελέτη της νέας τεχνολογίας, με την ικανότητα να αποδίδουμε στις θέσεις εργασίας μας ως μέλη της πρωτοπορίας, τότε θα προχωρήσουμε. Και αν σταδιακά συνηθίσετε να μετατρέπετε την παραγωγική σας εργασία σε κάτι που με το πέρασμα του χρόνου γίνεται ανάγκη, τότε αυτόματα θα γίνετε η πρωτοπόρα ηγεσία της νεολαίας και δεν θα προβληματιστείτε ξανά για το τι οφείλετε να κάνετε. Θα κάνετε απλά ότι τη δεδομένη στιγμή σας φαίνεται πιο λογικό. Δεν θα χρειάζεται να ψάχνετε να βρείτε τι είναι αυτό που ικανοποιεί τη νεολαία.

Θα είστε συγχρόνως νέοι αλλά και εκπρόσωποι της πρωτοπορίας της νεολαίας. Όσοι είναι νέοι, προπαντός νέοι στο πνεύμα, δεν χρειάζεται να ανησυχούν για το τι πρέπει να κάνουν για να ευχαριστήσουν τους άλλους. Να κάνετε απλά ότι είναι απαραίτητο, ότι σας φαίνεται λογικό τη δεδομένη στιγμή. Έτσι η νεολαία θα γίνει ηγεσία. Σήμερα έχουμε ξεκινήσει μια διαδικασία πολιτικοποίησης, αν μπορούμε να την ονομάσουμε έτσι, του Υπουργείου Βιομηχανίας. Το Υπουργείο είναι ένας πολύ ψυχρός χώρος, ένας πολύ γραφειοκρατικός χώρος, μια φωλιά βαρετών και σχολαστικών γραφειοκρατών, από τον υπουργό και κάτω, που βασανίζονται αδιάκοπα με συγκεκριμένα καθήκοντα προκειμένου να βρουν νέες σχέσεις και νέες συμπεριφορές. Εσείς λοιπόν ως οργάνωση νεολαίας παραπονεθήκατε ότι δεν παρακολούθησαν πολλοί τις εκδηλώσεις που οργανώσατε – ο χώρος ήταν άδειος τις μέρες που δεν ήμουν εγώ – και θα θέλατε να κάνω μια παρατήρηση. Μπορώ να πω κάτι, δεν μπορώ όμως να ζητήσω από κανέναν να έρθει εδώ. Τι ακριβώς συμβαίνει; Το πρόβλημα είναι απλά ότι είτε υπάρχει έλλειψη επικοινωνίας, είτε υπάρχει έλλειψη ενδιαφέροντος, και ότι σε κάθε περίπτωση το θέμα δεν έχει αντιμετωπιστεί από τους ανθρώπους που έχουν επιφορτιστεί να το κάνουν. Και αυτό είναι ένα συγκεκριμένο καθήκον του Υπουργείου. Είναι καθήκον της οργάνωσης νεολαίας, να υπερνικήσει την αδιαφορία που υπάρχει στο Υπουργείο. Αναμφίβολα, πάντα υπάρχει περιθώριο για ανάλυση και αυτοκριτική. Είναι πάντα επίκαιρη η εκτίμηση ότι δεν γίνονται όλα όσα είναι απαραίτητα ώστε να υπάρχει μια διαρκής επικοινωνία με τον κόσμο.

Σωστά. Όταν όμως κάποιος κάνει αυτοκριτική, πρέπει να είναι ολοκληρωμένη. Αυτοκριτική βέβαια δεν σημαίνει αυτομαστίγωση, αλλά έχει να κάνει με την ανάλυση της στάσης του καθενός. Και επιπλέον ο τεράστιος φόρτος εργασίας που κουβαλά ο καθένας στις πλάτες του – όπου στοιβάζονται το ένα πάνω στο άλλο τα καθήκοντα – σημαίνει ότι γίνεται πιο δύσκολο να υπάρξει μια άλλου είδους σχέση, να επιδιώξει κανείς μια σχέση πιο ανθρώπινη, θα μπορούσαμε να πούμε, μια σχέση λιγότερο εγκλωβισμένη στα γραφειοκρατικά κανάλια που σκάβουμε μέσα από το ατελείωτο χαρτομάνι.

Αυτό θα έρθει με τον καιρό, όταν η δουλειά δεν θα είναι τόσο πιεστική, όταν θα μπορεί κανείς να βασιστεί σε έναν επαρκή αριθμό στελεχών, όταν θα εκπληρώνονται πάντα όλα τα καθήκοντα, και όταν θα έχει εκλείψει η δυσπιστία απέναντι στην εργασία που είναι ένα από τα επονείδιστα στοιχεία που χαρακτηρίζουν ολόκληρο αυτό το στάδιο της επανάστασης μας. Σήμερα είναι απαραίτητο να ελέγχει κανείς προσωπικά κάθε έγγραφο, να κάνει ο ίδιος τους υπολογισμούς των στατιστικών στοιχείων, και πάλι ανακύπτουν λάθη. Όταν λοιπόν όλη αυτή η περίοδος παρέλθει – ήδη πλησιάζει προς το τέλος της και σύντομα θα εκλείψει – και όταν όλα τα στελέχη ισχυροποιηθούν, όταν θα έχουμε όλοι μας προοδεύσει λίγο ακόμα, τότε φυσικά θα υπάρχει χρόνος για άλλου είδους σχέσεις. Αυτό δεν σημαίνει ότι ο υπουργός ή ο διευθυντής θα βγαίνει να ρωτάει τον καθένα πως είναι η οικογένεια του. Σημαίνει ότι θα μπορούμε να οργανώσουμε σχέσεις που να μας επιτρέπουν να εργαζόμαστε καλύτερα και μέσα στο υπουργείο αλλά και έξω από αυτό, έτσι ώστε να γνωριστούμε καλύτερα.

Γιατί στόχος του σοσιαλισμού σήμερα, σε αυτήν τη φάση οικοδόμησης του σοσιαλισμού και του κομμουνισμού, δεν είναι απλά η δημιουργία αστραφτερών εργοστασίων. Τα εργοστάσια αυτά φτιάχνονται με στόχο τον ολοκληρωμένο άνθρωπο. Ο άνθρωπος θα πρέπει να μετασχηματίζεται παράλληλα με την ανάπτυξη της παραγωγής. Δεν θα κάναμε τη δουλειά μας αν ήμασταν αποκλειστικά παραγωγοί εμπορευμάτων και πρώτων υλών και δεν ήμασταν ταυτοχρόνως ικανοί να παράγουμε ανθρώπους. Πρόκειται εδώ για μια απο τις αποστολές της νεολαίας: να ωθήσει και να καθοδηγήσει, μέσω του παραδείγματος της, τη δημιουργία του μελλοντικού ανθρώπου. Σε αυτό το έργο δημιουργίας και καθοδήγησης συμπεριλαμβάνεται και η συγκρότηση του εαυτού μας, γιατί απέχουμε όλοι από το να είμαστε τέλειοι. Και όλοι θα πρέπει να βελτιωνόμαστε μέσα από τη δουλειά μας, τις διαπροσωπικές σχέσεις, μέσα από της σοβαρή μελέτη και τις αντιπαραθέσεις με κριτικό πνεύμα. Όλα αυτά συμβάλλουν στον μετασχηματισμό του ανθρώπου. Αυτό το γνωρίζουμε, μια που έχουν περάσει πέντε ολόκληρα χρόνια από τον θρίαμβο της επανάστασης μας. Επτά χρόνια πέρασαν επίσης από τότε που οι πρώτοι από εμάς αποβιβάστηκαν και ξεκίνησαν τον αγώνα, την τελική φάση του αγώνα. Όποιος κοιτάξει προς τα πίσω και αναλογιστεί πως ήταν ο ίδιος πριν επτά χρόνια θα αντιληφθεί ότι η απόσταση που έχουμε διανύσει είναι μεγάλη, πολύ μεγάλη, αλλά και ότι απομένει ακόμη αρκετός δρόμος.

Αυτοί είναι οι στόχοι μας. Είναι σημαντικό για τη νεολαία να κατανοήσει ποιός είναι ο ρόλος της και ποια είναι η βασική της αποστολή. Δεν χρειάζεται να παραφουσκώνει την σημασία του ρόλου αυτού, ούτε να θεωρεί τον εαυτό της ως κέντρο του σοσιαλιστικού σύμπαντος. Θα πρέπει όμως να βλέπει τον εαυτό της ως έναν σημαντικό κρίκο, έναν πολύ σημαντικό κρίκο που μας δείχνει το μέλλον.

Εμείς οδεύουμε προς τη δύση, παρόλο που, κατά μία έννοια γεωγραφική, ανήκουμε ακόμη στη νεολαία. Έχουμε φέρει σε πέρας πολλά δύσκολα καθήκοντα. Είχαμε την ευθύνη της καθοδήγησης μιας χώρας σε στιγμές τρομακτικά δύσκολες και αυτό βέβαια γερνά και φθείρει τους ανθρώπους. Σε μερικά χρόνια το καθήκον όσων από εμάς έχουν απομείνει θα είναι να αποσυρθούμε σε χειμερινά καταλύματα αφήνοντας τους νέους να καταλάβουν τις θέσεις μας. Όπως και να έχουν τα πράγματα, πιστεύω οτι εκπληρώσαμε με αρκετή αξιοπρέπεια μια αποστολή πολύ σημαντική. Δεν θα ήταν, όμως, το έργο μας ολοκληρωμένο αν δεν ξέραμε ποια είναι η κατάλληλη στγμή να αποσυρθούμε. Συμπληρωματικά, μια άλλη αποστολή σας είναι να διαμορφώσετε τους ανθρώπους που θα μας αντικαταστήσουν, έτσι ώστε το γεγονός ότι εμείς θα καλυφθούμε από τη λήθη, σαν κάτι που ανήκει στο παρελθόν, να αναδειχθεί σε ένα από τα πιο σημαντικά κριτήρια βάσει των οποίων θα αξιολογήσουμε τη δράση ολόκληρης της νεολαίας και ολόκληρου του λαού.

Πηγή: Ο Τσε Γκεβάρα μιλάει στους νέους (Che Guevara habla a la juventud / Che Guevara talks to young people), Pathfinder Press, 2000. Ελληνική Έκδοση: Διεθνές Βήμα, 2004.

Subcomandante Μάρκος: Για τον Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα

Του Κομαντάντε Μάρκος*.

Του Κομαντάντε Μάρκος*.

Πάνε σαράντα χρόνια από το 1966, όταν, αφού είχε βρεθεί στο «πουθενά» [1], ένας άνδρας προετοίμαζε τη μνήμη και την ελπίδα για να ξανάρθει η ζωή στην Αμερική. Το πολεμικό του όνομα ήταν τότε Ramon. Σε μιαν από τις πολυάριθμες γωνιές της αμερικανικής Πραγματικότητας, ο άνδρας εκείνος θυμόταν, και μες στις αναμνήσεις του ξαναζούσαν όλοι οι άνδρες και οι γυναίκες που έζησαν κι έδωσαν τις ζωές τους για την Αμερική. Το όνομα του και η μνήμη του θάφτηκαν από τους αιώνιους νεκροθάφτες της ιστορίας. Για κάποιους ονομαζόταν Ερνέστο και το επώνυμό του ήταν Γκεβάρα ντε λα Σέρνα. Για μας ήταν και παραμένει ο Τσε.

Στην Πούντα ντελ Έστε κατήγγειλε την πολιτική της εξουσίας, που, από τα γραφεία της Παγκόσμιας Τράπεζας, πρότεινε να χτιστούν απόπατοι ως λύση για της συνθήκες έσχατης αθλιότητας στις χώρες της Αμερικής. Από τότε, η φτώχεια στην Αμερική έχει αυξηθεί με την ίδια αναλογία που έχουν λεηλατηθεί τα πλούτη της από τους εύπορους όλων των εποχών. Η «αποπατοκρατία» επίσης αυξήθηκε, αλλά μόνο κατ΄όνομα. Σε μιαν από της χώρες της Αμερικής, πήρε το παράδοξο όνομα «Αλληλεγγύη». Ωστόσο, σε πείσμα των λεξικογραφικών αντικατοπτρισμών, η βασική λειτουργία της «αποπατοκρατίας» είναι πάντα η ίδια: σήμερα όπως και πάντα, οι φτωχοί βρίσκονται στο βάθος του απόπατου και οι πλούσιοι κάθονται στη λεκάνη.

Η κριτική της εξουσίας που έκανε ο Τσε δεν ισοδυναμεί με αποδοχή των μειονεκτημάτων της και απολογία ενός συστήματος. Επικρίνοντας το γεγονός ότι αντιτάσσουμε στην εξουσία παρόμοιες λογικές, ελάχιστα μεταμφιεσμένες από μια νέα ονομασία, έγραφε στα 1964: «Δεν ισχυρίζομαι ούτε κατά διάνοια ότι έχω ξεμπερδέψει με αυτό το ζήτημα, ούτε ότι έχω επιβάλει κάποιο είδος παπικής ευλογίας σε αυτές τις αντιφάσεις και σε κάποιες άλλες. Δυστυχώς, στα μάτια της πλειοψηφίας των λαών μας, ακόμη και στα δικά μου, η απολογία ενός συστήματος έχει μεγαλύτερες συνέπειες από την επιστημονική του ανάλυση».

Πολίτης του κόσμου, ο Τσε μας θυμίζει αυτό που γνωρίζαμε από την εποχή του Σπάρτακου, κάτι που ενίοτε ξεχνούσαμε: η ανθρωπότητα βρίσκει στην πάλη κατά των αδικιών μια κίνηση που την εξυψώνει, που την κάνει καλύτερη και πιο ανθρώπινη.

Λίγο αργότερα, η μνήμη και η ελπίδα κρατούν την πένα του όταν γράφει στην αποχαιρετιστήρια επιστολή του: «Μια μέρα, κάποιος πέρασε και ρώτησε ποιός έπρεπε να ειδοποιηθεί σε περίπτωση θανάτου, και η πραγματική πιθανότητα του θανάτου μας κατέλαβε όλους. Κατόπιν, γνωρίζαμε πως ήταν αλήθεια, πως στη διάρκεια μιας επανάστασης, είτε θριαμβεύεις είτε αποβιώνεις (αν πρόκειται για πραγματική επανάσταση). […] Άλλα εδάφη στον κόσμο διεκδικούν τη συνεισφορά των ταπεινών προσπαθειών μου». Κι έτσι ο Τσε ακολούθησε το δρόμο του.

Για να φύγει με άδεια, για να πεί «καλή αντάμωση», ο Τσε έλεγε «ως τη νίκη, πάντα», σα να ήθελε να πεί «θα ξαναβρεθούμε σύντομα». Σαράντα χρόνια αργότερα, ένα από εκείνα τα ξημερώματα που η σελήνη ανακτά τα κομμάτια του φωτός που του αποκόβει η μηνιαία δαγκωματιά του χρόνου, και που ένας κομήτης μεταμφιεσμένος σε φανοστάτη ξαγρυπνά μάταια στις πύλες της νύχτας, έψαξα ένα κείμενο για να τεκμηριώσω τα πρώτα μου λόγια γι’ αυτήν τη σκέψη.

Τα ξαναδιάβασα όλα, από τον Pablo Neruda στον Julio Cortazar, από τον Walt Whitman στον Juan Rulfo. Χαμένος κόπος, αδιάκοπα η εικόνα του Τσε με το ονειροπόλο βλέμμα του στο σχολείο του Λα Ιγκέρα [2], διεκδικούσε τη θέση της ανάμεσα στα χέρια μου. Από τη Βολιβία μας είχαν έλθει τα μισόκλειστα μάτια του κι εκείνο το ειρωνικό χαμόγελο που ιστορούσε όσα είχαν γίνει κι υποσχόταν όσα μέλλονταν να γίνουν.

Είπα «ονειροπόλο»; Ίσως έρπεπε να πω «νεκρό». Για κάποιους έχει πεθάνει, γι’ άλλους μόνο κοιμάται. Ποιός έχει άδικο; Πάντα σαράντα χρόνια που ο Τσε προετοίμαζε τη μεταμόρφωση της αμερικανικής πραγματικότητας και η εξουσία προετοίμαζε την εξουδετέρωση του. Πάνε σαράντα χρόνια που η εξουσία διαβεβαίωνε ότι το τέλος της ιστορίας είχε λάβει χώρα στη χαράδρα ντελ Γιούρο [3]. Ισχυριζόταν ότι η δυνατότητα για έναν κόσμο καλύτερο, διαφορετικό, είχε καταστραφεί οριστικά. Υπεστήριζε ότι ο καιρός των εξεγέρσεων είχε τελειώσει.

Από το βιβλίο των Μισέλ Λεβί και Ολιβιέ Μπεσασενό «Che Guevara: His Revolutionary Legacy» (2009). Μετάφραση στα γαλλικά απ’ το ισπανικό πρωτότυπο: Laurence Villaume. Ελληνική Μετάφραση: Νίκος Σταμπάκης (εκδ.Φαρφουλάς). Η ακριβής ημερομηνία σύνταξης του κειμένου δεν είναι γνωστή.

[1] Ο υποδιοικητής Μάρκος αναφέρεται εδώ στη χρονιά που ο Τσε εγκατέλειψε την Κούβα και «εξαφανίστηκε» για να βοηθήσει τον ανταρτοπόλεμο στο Κονγκό. Βλ. Paco Ignacio Taibo II, με τους Froilan Escobar και Felix Guerra, El Ano en que estuvimos en nunguna parte, Mortiz, Mexico DF, 1994 – γαλλική μετάφραση L’ Annee ou nous n’etions nulle part, Metaille, Παρίσι, 1995 (Σημ. γαλλικής μετάφρασης).

[2] Σε μια σχολική αίθουσα στο χωριό Λα Ιγκέρα, ο Τσε κρατήθηκε μιαν ολόκληρη νύχτα και εκτελέστηκε δια συνοπτικών διαδικασιών την επομένη, στις 8 Οκτωβρίου 1967, κατά το τέλος του πρωινού, από τις ειδικές βολιβιανές δυνάμεις, κατόπολη εντολής της CIA (Σημ. γαλλικής μετάφρασης).

[3] Στις 7 Οκτωβρίου 1967, ο Τσε Γκεβάρα, αφού πληγώθηκε στα πόδια και καταστράφηκε το τουφέκι του από σφαίρες (το πιστόλι του είχε μείνει από πυρομαχικά) , συνελήφθη ενώ οδηγούσε ένα απόσπασμα στη χαράδρα Κεμπράδα ντελ Γιούρο.

* Εκπρόσωπος του Στρατού των Ζαπατίστας για την Εθνική Απελευθέρωση (EZLN), κινήματος για την αυτοδιάθεση των ιθαγενών του Μεξικού.

«

« Crear dos, tres… muchos Vietnam, es la consigna. Es la hora de los hornos y no se ha de ver más que la luz.

Crear dos, tres… muchos Vietnam, es la consigna. Es la hora de los hornos y no se ha de ver más que la luz.