Ελληνικό Αρχείο Τσε Γκεβάρα © Guevaristas

Η πρώτη και πληρέστερη ελληνική ιστοσελίδα για τον Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα.

Ελληνικό Αρχείο Τσε Γκεβάρα © Guevaristas

Η πρώτη και πληρέστερη ελληνική ιστοσελίδα για τον Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα.

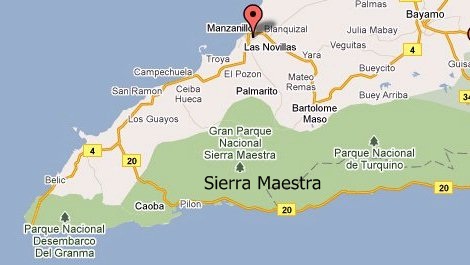

Το όνομα της Σιέρρα Μαέστρα (Sierra Maestra) είναι άρρηκτα συνδεδεμένο με την Κουβανική Επανάσταση και, επομένως, με τον ίδιο τον Τσε. Η οροσειρά που βρίσκεται στα δυτικά της επαρχίας Οριέντε, στο νότιο άκρο της Κούβας, έχει υπάρξει μάρτυρας σημαντικών ανταρτοπολέμων – από τον Πόλεμο των Δέκα Ετών επί ισπανικής αποικιοκρατίας στα μέσα του 19ου αιώνα μέχρι τον αγώνα γιά την Κουβανική ανεξαρτησία και φυσικά τη δράση του Επαναστατικού Κινήματος της 26ης Ιουλίου ενάντια στο καθεστώς Μπατίστα. Στις δύσβατες βουνοπλαγιές της Σιέρρα Μαέστρα ο Φιντέλ Κάστρο και οι σύντροφοι του οργάνωσαν τον αντάρτικο αγώνα ενάντια στα στρατεύματα της Κουβανικής δικτατορίας, δίνοντας μιά θρυλική – ιστορικής σημασίας – διάσταση στα απόκρυμνα δάση της επαρχίας Οριέντε.

Το όνομα της Σιέρρα Μαέστρα (Sierra Maestra) είναι άρρηκτα συνδεδεμένο με την Κουβανική Επανάσταση και, επομένως, με τον ίδιο τον Τσε. Η οροσειρά που βρίσκεται στα δυτικά της επαρχίας Οριέντε, στο νότιο άκρο της Κούβας, έχει υπάρξει μάρτυρας σημαντικών ανταρτοπολέμων – από τον Πόλεμο των Δέκα Ετών επί ισπανικής αποικιοκρατίας στα μέσα του 19ου αιώνα μέχρι τον αγώνα γιά την Κουβανική ανεξαρτησία και φυσικά τη δράση του Επαναστατικού Κινήματος της 26ης Ιουλίου ενάντια στο καθεστώς Μπατίστα. Στις δύσβατες βουνοπλαγιές της Σιέρρα Μαέστρα ο Φιντέλ Κάστρο και οι σύντροφοι του οργάνωσαν τον αντάρτικο αγώνα ενάντια στα στρατεύματα της Κουβανικής δικτατορίας, δίνοντας μιά θρυλική – ιστορικής σημασίας – διάσταση στα απόκρυμνα δάση της επαρχίας Οριέντε.

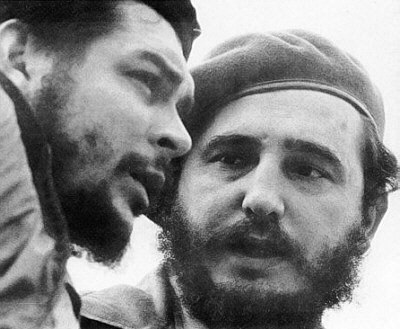

Starting out from the idea that rectification means, as I’ve said before, looking for new solutions to old problems, rectifying many negative tendencies that had been developing; that rectification implies making more accurate use of the system which, as we said at the enterprises meeting, was a horse, a lame nag with may sores that we were treating with mercurochrome and prescribing medicines for, putting splints on one leg, in short, fixing up the nag, the horse. I said that the thing to do now was to go on using that horse, knowing its bad habits, the perils of that horse, how it kicked and bucked, and try to lead it on our path and not go wherever it wishes to take us. I’ve said, let us take up the reins!

Starting out from the idea that rectification means, as I’ve said before, looking for new solutions to old problems, rectifying many negative tendencies that had been developing; that rectification implies making more accurate use of the system which, as we said at the enterprises meeting, was a horse, a lame nag with may sores that we were treating with mercurochrome and prescribing medicines for, putting splints on one leg, in short, fixing up the nag, the horse. I said that the thing to do now was to go on using that horse, knowing its bad habits, the perils of that horse, how it kicked and bucked, and try to lead it on our path and not go wherever it wishes to take us. I’ve said, let us take up the reins! I simply ask that in a cultured country, in a cultured world, in a world where ideas are discussed, Che’s economic theories should be made known I especially ask that our students of economics, of whom we have many and who read all kinds of pamphlets, manuals, theories abut capitalist categories and capitalist laws, also begin to study Che’s economic thought, so as to enrich their knowledge. It would be a sign of ignorance to believe there is only way of doing things arising from the concrete experience of a specific time and specific historical circumstances. What I ask for, what I limit myself to asking for, is a little more knowledge, consisting of knowing about other points-of-view, points-of-view as respected, as deserving and as coherent as Che’s points-of-view.

I simply ask that in a cultured country, in a cultured world, in a world where ideas are discussed, Che’s economic theories should be made known I especially ask that our students of economics, of whom we have many and who read all kinds of pamphlets, manuals, theories abut capitalist categories and capitalist laws, also begin to study Che’s economic thought, so as to enrich their knowledge. It would be a sign of ignorance to believe there is only way of doing things arising from the concrete experience of a specific time and specific historical circumstances. What I ask for, what I limit myself to asking for, is a little more knowledge, consisting of knowing about other points-of-view, points-of-view as respected, as deserving and as coherent as Che’s points-of-view. For example, voluntary work, the brainchild of Che and one of the best things he left us during his stay in our country and his part in the revolution, was steadily on the decline. It became a formality almost. It would be done on the occasion of a special date, a Sunday. People would sometimes run around and do things in a disorganized way. The bureaucrat’s view, the technocrat’s view that voluntary work was neither basic nor essential gained more and more ground. The idea was that voluntary work was kind of silly, a waste of time, that problems had to be solved with overtime, and with more and more overtime, and this while the regular work-day was not even being used efficiently. We had fallen into a whole host of habits that Che would have been really appalled at.

For example, voluntary work, the brainchild of Che and one of the best things he left us during his stay in our country and his part in the revolution, was steadily on the decline. It became a formality almost. It would be done on the occasion of a special date, a Sunday. People would sometimes run around and do things in a disorganized way. The bureaucrat’s view, the technocrat’s view that voluntary work was neither basic nor essential gained more and more ground. The idea was that voluntary work was kind of silly, a waste of time, that problems had to be solved with overtime, and with more and more overtime, and this while the regular work-day was not even being used efficiently. We had fallen into a whole host of habits that Che would have been really appalled at. really managed to develop a rather elaborate and very profound theory on the manner in which, in his opinion, socialism would be built leading to a communist society.

really managed to develop a rather elaborate and very profound theory on the manner in which, in his opinion, socialism would be built leading to a communist society. I say this because it is my deepest conviction that if his thought remains unknown it will be difficult to get very far, to achieve real socialism, really revolutionary socialism, socialism with socialists, socialism and communism with communists. I’m absolutely convinced that ignoring those ideas would be a crime. That’s what I’m putting to you. We have enough experience to know how to do things; and there are extremely valuable principles of immense worth in Che’s ideas and thought that simply go beyond the image that many people have of Che as a brave, heroic, pure man; of Che as a saint because of his virtues; as a martyr because of his selflessness and heroism. Che was also a revolutionary, a thinker, a man of doctrine, a man of great ideas, who was capable with great consistency of working out instruments and principles that unquestionably are essential to the revolutionary path.

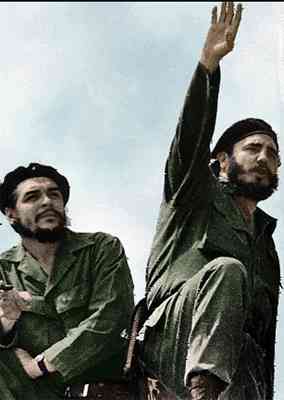

I say this because it is my deepest conviction that if his thought remains unknown it will be difficult to get very far, to achieve real socialism, really revolutionary socialism, socialism with socialists, socialism and communism with communists. I’m absolutely convinced that ignoring those ideas would be a crime. That’s what I’m putting to you. We have enough experience to know how to do things; and there are extremely valuable principles of immense worth in Che’s ideas and thought that simply go beyond the image that many people have of Che as a brave, heroic, pure man; of Che as a saint because of his virtues; as a martyr because of his selflessness and heroism. Che was also a revolutionary, a thinker, a man of doctrine, a man of great ideas, who was capable with great consistency of working out instruments and principles that unquestionably are essential to the revolutionary path. When we toured it we were deeply impressed and talked with many compañeros, the members of the Central Committee about what they were doing in the factory, which is advancing at a rapid pace; what was being done in construction. We realized the great future of this factory as a manufacturer of components, of vanguard technology, which will have a major impact on development and productivity, on the automation of production processes. When we toured your first-rate factory and saw the ideas you had which are being put into practice, we realized it would become a huge complex of many thousands of workers, the pride of the province and the pride of the country. In the next five years, more than 100-million pesos will be invested in it to make it a real giant. When we learned that the workers wanted to name it after Che because he was so concerned with electronics, computers and mathematics, the leadership of our party decided that this was where the ceremony marking the twentieth anniversary of Che’s death should be held, and that factory should be given the glorious and beloved name of Ernesto Che Guevara.

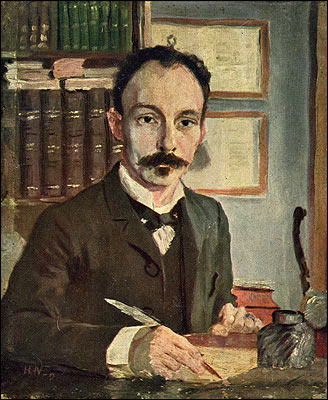

When we toured it we were deeply impressed and talked with many compañeros, the members of the Central Committee about what they were doing in the factory, which is advancing at a rapid pace; what was being done in construction. We realized the great future of this factory as a manufacturer of components, of vanguard technology, which will have a major impact on development and productivity, on the automation of production processes. When we toured your first-rate factory and saw the ideas you had which are being put into practice, we realized it would become a huge complex of many thousands of workers, the pride of the province and the pride of the country. In the next five years, more than 100-million pesos will be invested in it to make it a real giant. When we learned that the workers wanted to name it after Che because he was so concerned with electronics, computers and mathematics, the leadership of our party decided that this was where the ceremony marking the twentieth anniversary of Che’s death should be held, and that factory should be given the glorious and beloved name of Ernesto Che Guevara. Ο Χοσέ Μαρτί, ποιητής και κορυφαίος μαχητής της Κουβανικής ανεξαρτησίας, είναι από τις πλέον εμβληματικές φυσιογνωμίες της ιστορίας της Κούβας. Αποτέλεσε σημείο αναφοράς και έμπνευσης γιά τους ηγέτες της Επανάστασης στο νησί και ιδιαίτερα γιά τον Τσε Γκεβάρα και τον Φιντέλ Κάστρο. Γεννημένος το 1853 στην Αβάνα από ισπανούς γονείς, άρχιζε να δημοσιεύει ποίηματα του σε τοπικές εφημερίδες σε ηλικία μόλις 16 ετών. Το 1869, η υποστήριξη που παρείχε μέσω των γραπτών του στους ξεσηκωμένους κουβανούς ενάντια στο αποικιοκρατικό καθεστώς, τον έβαλε σε σοβαρά προβλήματα. Συνελήφθη και καταδικάστηκε σε έξι χρόνια καταναγκαστική εργασία γιά προδοσία και υποκίνηση ανταρσίας. Με παρέμβαση των γονιών του η ποινή του μειώθηκε, ο ίδιος όμως εξορίστηκε στην Ισπανία. Ευρισκόμενος στην Ευρώπη ο Μαρτί σπούδασε Νομικά συνεχίζοντας ταυτόχρονα να γράφει γιά την κατάσταση που επικρατούσε στην Κούβα. Κατά την ίδια περίοδο χρειάστηκε να χειρουργηθεί δύο φορές προκειμένου να διορθωθεί η βλάβη που είχαν υποστεί τα πόδια του από τις χειροπέδες των φυλακών.

Ο Χοσέ Μαρτί, ποιητής και κορυφαίος μαχητής της Κουβανικής ανεξαρτησίας, είναι από τις πλέον εμβληματικές φυσιογνωμίες της ιστορίας της Κούβας. Αποτέλεσε σημείο αναφοράς και έμπνευσης γιά τους ηγέτες της Επανάστασης στο νησί και ιδιαίτερα γιά τον Τσε Γκεβάρα και τον Φιντέλ Κάστρο. Γεννημένος το 1853 στην Αβάνα από ισπανούς γονείς, άρχιζε να δημοσιεύει ποίηματα του σε τοπικές εφημερίδες σε ηλικία μόλις 16 ετών. Το 1869, η υποστήριξη που παρείχε μέσω των γραπτών του στους ξεσηκωμένους κουβανούς ενάντια στο αποικιοκρατικό καθεστώς, τον έβαλε σε σοβαρά προβλήματα. Συνελήφθη και καταδικάστηκε σε έξι χρόνια καταναγκαστική εργασία γιά προδοσία και υποκίνηση ανταρσίας. Με παρέμβαση των γονιών του η ποινή του μειώθηκε, ο ίδιος όμως εξορίστηκε στην Ισπανία. Ευρισκόμενος στην Ευρώπη ο Μαρτί σπούδασε Νομικά συνεχίζοντας ταυτόχρονα να γράφει γιά την κατάσταση που επικρατούσε στην Κούβα. Κατά την ίδια περίοδο χρειάστηκε να χειρουργηθεί δύο φορές προκειμένου να διορθωθεί η βλάβη που είχαν υποστεί τα πόδια του από τις χειροπέδες των φυλακών.