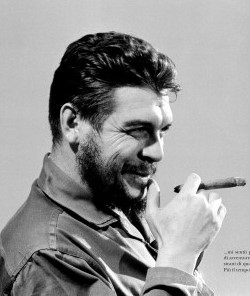

Κατηγορία: Ernesto Che Guevara

Cuba and the U.S.: Che Guevara’s interview to Monthly Review

The questions below were submitted, in writing, to Comandante Guevara by Leo Huberman during the week of the Bay of Pigs invasion; the answers were received the end of June 1961.

The questions below were submitted, in writing, to Comandante Guevara by Leo Huberman during the week of the Bay of Pigs invasion; the answers were received the end of June 1961.

1. Have relations with the U.S. gone “over the brink” or is it still possible to work out a modus vivendi?

This question has two answers: one, which we might term “philosophical,” and the other, “political.” The philosophical answer is that the aggressive state of North American monopoly capitalism and the accelerated transition toward fascism make any kind of agreement impossible; and relations will necessarily remain tense or even worse until the final destruction of imperialism. The other, political answer, asserts that these relations are not our fault, and that, as we have many times demonstrated, the most recent time being after the defeat of the Giron Beach landing, we are ready for any kind of agreement on terms of equality with the Government of the United States.

2. The U.S. holds Cuba responsible for the rupture in relations while Cuba blames the U.S. What part of the blame, in your opinion, can be correctly attributed to your country? In short, what mistakes have you made in your dealings with the U.S.?

Very few, we believe; perhaps some in matters of form. But we hold the firm conviction that we have acted for our part in accord with the right, and that we have responded to the interests of the people in each of our acts. The trouble is that our interests, that is, those of the people, and the interests of the North American monopolies are at variance.

3. Assuming that the U.S. means to smash the Cuban Revolution, what are the chances of its getting help from the O.A.S. group?

Everything depends on what is meant by “smash.” If this means the violent destruction of the revolutionary regime with the help—likewise direct—of the O.A.S., I believe there is very little possibility, because history cannot be ignored. The countries of America understand the value of active solidarity among friendly countries, and they would not risk a reversal of such magnitude.

4. Does Cuba align itself in international affairs with the neutralist or Soviet bloc?

Cuba will align herself with justice; or, to be less absolute, with what she takes for justice. We do not practice politics by blocs, so that we cannot side with the neutralist bloc, nor, for the same reason, do we belong to the socialist bloc. But wherever there is a question of defending a just cause, there we will cast our votes—even on the side of the United States if that country should ever assume the role of defending just causes.

5. What is Cuba’s chief domestic problem?

It is difficult to assess problems with such precision. I can mention several: the “guerrillerismo” which still exists in the government; the lack of comprehension on the part of some sectors of the people of the necessity for sacrifice; the lack of some raw materials for industries and some non-durable consumer goods, resulting in certain scarcities; the uncertainty as to when the next imperialist attack will take place; the upsets in production caused by mobilization. These are some of the problems which trouble us at times, but, far from distressing us, they serve to accustom us to the struggle.

6. How do you explain the growing number of Cuban counter-revolutionaries and the defection of so many former revolutionaries?

Revolutions function by waves. When Mr. Huberman asked this question, perhaps it was accurate, but today there are fewer counter-revolutionaries than before Giron Beach. The counter-revolutionary attack increased slowly until it reached its climax on Giron Beach; then it was defeated and fell drastically to zero. Now that it is again attempting to raise its head and inflict new harm, our intention is to eliminate the counter-revolutionaries.

The defections of more or less prominent figures are due to the fact that the socialist revolution left the opportunists, the ambitious, and the fearful far behind and now advances toward a new regime free of this class of vermin.

7. Can the countries of Latin America solve their problems while maintaining the capitalist system, or must they take the path of socialism as Cuba has done?

It seems elementary to us that the way of the socialist revolution must be chosen, the exploitation of man by man must be abolished, economic planning must be undertaken, and all means of assisting the public welfare must be placed at the service of the community.

8. Are civil liberties, Western style, permanently finished while your government is in power?

This would depend on what civil rights were referred to—the civil right, for example, of the white to make the Negro sit in the rear of a bus; the right of the white to keep the Negro off a beach or bar him from a certain zone; the right of the Ku Klux Klan to assassinate any Negro who looks at a white woman; the right of a Faubus, in a word, or perhaps the right of a Trujillo, or Somoza, or Stroessner, or Duvalier. In any case, it would be necessary to define the term more precisely, to see if it also includes the right to welcome punitive expeditions sent by a country to the north.

9. What kind of political system do you envisage for Cuba after the present emergency period of reorganization and reconstruction is over?

In general terms it may be said that a political power which is attentive to the needs of the majority of the people must be in constant communication with the people and must know how to express what the people, with their many mouths, only hint at. How to achieve this is a practical task which will take us some time. In any event, the present revolutionary period must still persist for some time, and it is not possible to talk of structural reorganization while the threat of war still haunts our island.

Monthly Review, 1961, Volume 13, Issue 05 (September) / Cuba and the U.S.

Read the Greek version.

ΑΛΕΙΔΑ ΓΚΕΒΑΡΑ: «Ο μπαμπάς μας δίδαξε να είμαστε Λατινοαμερικανοί» – ALEIDA GUEVARA: “Papá nos enseñó a ser latinoamericanos”

Έχει την ίδια εμφάνιση με τον διάσημο πατέρα της, που τόσες εκατομμύρια φορές έχουμε δει σε φωτογραφίες και ντοκιμαντέρ. Βαθουλωμένα μάτια, μικρά και πολύ υγρά πίσω από δύο εξέχοντα ζυγωματικά.

Έχει την ίδια εμφάνιση με τον διάσημο πατέρα της, που τόσες εκατομμύρια φορές έχουμε δει σε φωτογραφίες και ντοκιμαντέρ. Βαθουλωμένα μάτια, μικρά και πολύ υγρά πίσω από δύο εξέχοντα ζυγωματικά.

Με το πέρασμα των λεπτών, οι λέξεις γίνονται λόγια και χαμόγελα τα οποία μετά μετατρέπονται γρήγορα σε γέλια. Τα δάκρυα τρέχουν για λίγο σε ένα σύντομο απόσπασμα από τη συνέντευξη. Απίστευτο γιατί σίγουρα έχει ακούσει και θυμηθεί χιλιάδες φορές τον πατέρα της σε όλα αυτά τα χρόνια, ο οποίος πέθανε όταν αυτή ήταν μόλις έξι ετών. Η Ζούγκλα της Βολιβίας της τον είχε αφαιρέσει και της τον κράτησε κρυφό για σχεδόν τέσσερις δεκαετίες.

Η Αλέιδα ήρθε στην Αργεντινή για να παρουσιάσει το αδημοσίευτο βιβλίο της μητέρας της, της Αλέιδα Μαρτς, η οποία ερωτεύτηκε στη Σιέρα Μαέστρα τον Τσε, όταν το κίνημα της 26ης Ιουλίου αγωνίστηκε και εν τέλη κατάφερε το 1959 την εκδίωξη της δικτατορίας του Φουλχένσιο Μπατίστα στη Κούβα.

Αναπόληση – Η ζωή μου με τον Τσε: αφηγείται τα χνάρια της ζωή της στο πλευρό του. Δασκάλα από την εξοχή, εντάχθηκε στον αγώνα, άλλαξε τη ζωή της, άφησε πίσω την οικογένειά της, μοιράστηκε τον θρίαμβο της Επανάστασης μαζί του, τον παντρεύτηκε και απέκτησε μαζί του τέσσερα παιδιά.

Η Αλέιδα Γκεβάρα, τώρα, ταξιδεύει στον κόσμο, τόσο ως παιδίατρος αλλά κάνει και εθελοντική εργασία καθώς επιθυμεί να διαδώσει το έργο και τις επαναστατικές ιδέες των γονιών της.

«Η πόλη μου είναι εξωφρενικά θορυβώδης, αλλά υπήρξε μια μέρα που ήταν πλήρως σιωπηλή. Ήταν όταν τα λείψανά του πατέρα μου έφτασαν στην Κούβα από την Βολιβία και μεταφέρθηκαν οδικώς με πομπή από της Αβάνα στη Σάντα Κλάρα.»

«Ο πατέρας μου, χωρίς λόγια, ήταν ένας άνθρωπος που ήξερε πώς να αγαπά»

Tiene la misma mirada del ce’lebre personaje, millones de veces difundido en fotos y documentales de e’poca. Los ojos hundidos, pequen~os y hu’medos muy detra’s de dos po’mulos prominentes. Aleida Guevara pone distancia so’lo al principio. Con el correr de los minutos, las palabras pasan a ser verborragia y las sonrisas se transforman en carcajadas. Resultan increi’bles sus la’grimas durante un breve pasaje de la entrevista. Increi’bles porque seguramente ese mismo recuerdo la sorprendio’ miles de veces. Ernesto “Che” Guevara murio’ cuando ella contaba con so’lo seis an~os. La selva boliviana se lo habi’a quitado para mantenerlo oculto por casi cuatro de’cadas. Aleida llego’ a la Argentina para presentar el libro ine’dito de su madre, Aleida March, que se enamoro’ del Che en plena Sierra Maestra, cuando el movimiento 26 de Julio peleaba en desventaja para desalojar a la dictadura de Cuba.

Evocacio’n. Mi vida al lado del Che recorre la vida de una campesina que siendo maestra se sumo’ a la lucha, cambio’ de vida a espaldas de su familia, compartio’ el triunfo de la Revolucio’n, se caso’ y tuvo cuatro hijos. Pero que tambie’n sufrio’ las ausencias de un marido que troto’ el planeta en pos del mismo ideario que lo condujo a los cargos ma’s importantes de su patria de adopcio’n. Aleida Guevara tambie’n recorre el mundo, lo hace tanto como pediatra voluntaria como tambie’n para difundir la obra de sus padres y asegura que cada vez que sale de su querida isla muere por volver. No es su primera vez aqui’. En una ocasio’n viajo’ a Rosario para visitar la casa que habi’a sido de su papa’. Cuando llego’ a la puerta, noto’ que faltaba la placa de bronce. Alguien le comunico’ que un explosivo la habi’a volado y tuvo que escuchar a una vecina indignada por el estruendo.

–?Que’ sintio’ ante semejante bienvenida?

–Esa sen~ora culpaba al Che por el petardo. No dije nada, pero desde los medios le conteste’ diciendo que si la gente no era capaz de defender una simple placa, ?co’mo iba a hacerlo frente a algo ma’s importante, como la vida.? En cuanto al pai’s no me pasa nada en particular. Papa’ nos ensen~o’ a ser latinoamericanos, porque lo era en serio. En Cuba nos educamos con la palabra de Jose’ Marti’, que deci’a que la patria abarcaba desde el Ri’o Bravo hasta la Patagonia. Hemos vivido mucho con argentinos, guerrilleros o no, que visitaban la isla y queri’an conocer a los hijos del Che, asi’ que siempre nos rodearon y ya estamos bastante interiorizados.

–?Por que’ cree que su madre tardo’ tanto en escribir su biografi’a?

–Tienes que pensar que ella tuvo que fabricarse una represa para seguir viviendo para sus hijos. Ernesto Guevara fue su primer novio, el padre de sus hijos, su maestro, gui’a, compan~ero y co’mplice. Fue el todo y de pronto, esta mujer tuvo que aprender a vivir sin e’l. Cuando e’ramos muy pequen~os, ella nos daba el beso de las buenas noches y hasta juga’bamos a los almohadazos. Cuando muere mi padre, todo eso se acaba. Ella segui’a caminando, viviendo porque debi’a hacerlo, pero seguro que era muy difi’cil. Tuvo que encerrarse para poder seguir adelante. Es una mujer parca e introvertida como toda campesina cubana que cuando conocio’ Buenos Aires admiro’ ma’s todavi’a a mi papa’, que dejo’ esta inmensidad para irse a esa islita del Caribe.

–?Co’mo es nacer y crecer hija de una pareja de revolucionarios?

–Es una historia muy linda, y te dara’s cuenta de que soy una mujer muy feliz solamente por ser fruto de un amor tan intenso. Eso te da una categori’a tremenda como ser humano. En una sociedad donde te permiten todo el tiempo actuar con los seres humanos eres una persona feliz. Tengo un privilegio, que es el de haber recibido tanto de esas dos personas y la mejor manera de devolver tanto es ser mejor con tu pueblo y lo ma’s u’til con ellos.

–En el libro se publican cartas de su padre. Difi’cil imaginar a un comandante con voz de mando tan carin~oso con su esposa.

–Una persona que lo conocio’ en A’frica quedo’ impresionado con aquel hombre que en medio de un atardecer dijo que extran~aba a su mujer y se puso a recitar un poema a la distancia. Mi padre era un argentino sui generis en ese sentido y aqui’ le cuento otra cosa. E’l hace una cri’tica muy interesante en su primer libro Notas de viaje, sobre su propio pai’s. Es sobre la pe’rdida de las rai’ces culturales en contraste con otros pai’ses que tuvo la suerte de recorrer. Pero es despue’s del triunfo revolucionario en Cuba cuando empieza a crecer como hombre, donde tiene que llevar a la pra’ctica todo lo que teni’a en la cabeza. Eso le paso’ an~os despue’s en su experiencia africana, desde donde tuvo que irse con un sentimiento de tristeza al no haber tenido tiempo para desarrollar en la pra’ctica sus ideas.

La charla va y viene, pasa por Aleida March a Aleidita y sus sentimientos como hija. A su tarea como me’dica en diferentes pai’ses, pero que dejo’ una huella enorme tambie’n en Angola. “Esos dos an~os alli’ fueron increi’bles. Siempre digo que Dante Alighieri hubiera conseguido material suficiente para describir el infierno”. Pronto, hablaremos de Cuba y del mundo aunque invariablemente el Che vuelva a escena. “E’l fue capaz de ir a dar todo por otro pai’s que no era el suyo y amarlo con tanta intensidad y tan sinceramente. Es uno de dos hombres que no nacieron en territorio nacional y llevan la nacionalidad cubana de nacimiento. Mi pueblo tiene fama de escandaloso y bullicioso, pero hubo un di’a en el que hizo silencio. Fue cuando llegaron sus restos y al paso del fe’retro, que recorrio’ el camino desde La Habana hasta Santa Clara. Yo trabajo con un grupo de nin~os minusva’lidos que no lo conocieron y que sin embargo lloraron. Cuando estuve en Bolivia visitando el lugar donde pusieron su cuerpo, habi’a centenares de me’dicos cubanos y paso’ lo mismo.”

–?Que’ opinari’a el Che de los cambios en Cuba?

–No se trata de cambios, sino de soluciones a antiguos problemas que nosotros teni’amos. Era inevitable que ocurriera porque este es un proceso de evolucio’n y dentro de la revolucio’n debe cambiarse todo lo que debe ser cambiado. Es algo normal dentro de una sociedad que va tomando ma’s taman~o desde el punto de vista econo’mico y del desarrollo social. Ahora tienes ma’s posibilidades de liberar un monto’n de cosas, se pueden hacer aperturas como dicen ustedes aqui’. La cuestio’n dentro de una sociedad es que tienes que aprender de los problemas que se van presentando porque errores se van a cometer toda la vida. Ahora estamos en un proceso de que el Estado cubano decide que no puede seguir manteniendo a un grupo de trabajadores que no son productivos, no se los puede sostener pero no por ello dejarlos en la calle. Entonces se les da la posibilidad de que trabajen por cuenta propia, y recursos para que puedan hacerlo. Creo que nuestro futuro estara’ en desarrollar cooperativas de servicios, que tiene ma’s que ver con nuestra sociedad que con la cosa individual.

–El llamado Primer Mundo colapso’. ?Fidel Castro y el Che teni’an razo’n o todo esta’ al reve’s?

–Por ahora no podemos cantar victoria porque el capitalismo tiene muchos mecanismos para resolver situaciones de este tipo y la peor que nos puede caer encima es una guerra. Es un recurso que han ido probando en distintas partes del mundo. Suerte para nosotros porque estamos alejados y podemos mantener por ahora nuestra propia autonomi’a, pero vamos a ver. La forma en co’mo ellos superaban las cosas ya fue vista en las sucesivas crisis ocurridas durante el siglo pasado.

–?No hay lugar para el optimismo entonces?

–Hay lugar, pero seri’a bueno que los gringos despertaran de su letargo. Los u’nicos que le pueden decir dicen no a las guerras son ellos, el pueblo. Son los u’nicos que pueden frenar la locura, tal como lo hicieron durante la guerra con Vietnam.

–?Que’ recuerdos tiene de su infancia junto al Che?

–Muy poco porque naci’ en 1960. Mientras yo creci’a, e’l daba dos veces la vuelta al mundo. Tengo el recuerdo de papi lleva’ndome a un corte de can~a siendo yo muy chiquita. Debo haber protestado por aquel madrugo’n pero no se’ co’mo se las arreglo’ para entretenerme. De alguna manera me quede’ tranquila sobre la pila de can~as mientras e’l cortaba y hablaba conmigo al mismo tiempo. Tengo ima’genes de mi padre llegando a la casa, quita’ndose casi toda la ropa. Nos subi’amos sobre su espalda, como si fuera un caballito, y nos paseaba por todo el pasillo. Hay otra imagen muy linda que se me grabo’ y que creo que corresponde a sus u’ltimos di’as en Cuba. Estaba vestido de militar en su cuarto, con mami enfrente, vestida con una bata. Mi hermano ma’s pequen~o en sus hombros y enorme mano acariciando su cabecita. Yo mire’ esa escena, nadie me la conto’, y quiza’ fue la u’ltima que tuve. A los diecise’is an~os comenzaron a aparecer esos recuerdos en mi’. Mi papa’, sin palabras, era un hombre que sabi’a amar. Logre’ darme cuenta de eso. Mi infancia transcurrio’ y no extran~e’ a papa’, lo tuve y lo siento presente, y ese es un logro de mi madre.

Πηγή: Sierra Maestra / http://veintitres.infonews.com, Myrsini Tsakiri.

Letter to Fidel Castro about the situation in Congo 1965

Το παρακάτω εστάλη από τον Τσε Γκεβάρα στον Φιντέλ Κάστρο στις 5 Οκτωβρίου 1965, δηλαδή τρείς ημέρες αφότου είχε αποστείλει το γράμμα του αποχαιρετισμού. Ο Τσε εξηγεί αναλυτικά στον Σύντροφο του την κατάσταση που επικρατούσε στο Κονγκό, στο οποίο είχε πάει γιά να συνδράμει τοπική μαρξιστική ομάδα ανταρτών. Η αποστολή του γράμματος – και ο τρόπος γραφής του Τσε – αποδεικνύει τους δεσμούς φιλίας και εμπιστοσύνης που συνέδεε τους δύο άνδρες, παρά το γεγονός ότι ο Γκεβάρα είχε πλέον εγκαταλείψει την Κούβα.

Το παρακάτω εστάλη από τον Τσε Γκεβάρα στον Φιντέλ Κάστρο στις 5 Οκτωβρίου 1965, δηλαδή τρείς ημέρες αφότου είχε αποστείλει το γράμμα του αποχαιρετισμού. Ο Τσε εξηγεί αναλυτικά στον Σύντροφο του την κατάσταση που επικρατούσε στο Κονγκό, στο οποίο είχε πάει γιά να συνδράμει τοπική μαρξιστική ομάδα ανταρτών. Η αποστολή του γράμματος – και ο τρόπος γραφής του Τσε – αποδεικνύει τους δεσμούς φιλίας και εμπιστοσύνης που συνέδεε τους δύο άνδρες, παρά το γεγονός ότι ο Γκεβάρα είχε πλέον εγκαταλείψει την Κούβα.

Congo, 5.10.1965

Dear Fidel,

I received your letter, which has aroused contradictory feelings in me — for in the name of proletarian internationalism, we are committing mistakes that may prove very costly. I am also personally worried that, either because I have failed to write with sufficient seriousness or because you do not fully understand me, I may be thought to be suffering from the terrible disease of groundless pessimism.

When your Greek gift [Emilio Aragones, a member of the Cuban central committee] arrived here, he told me that one of my letters had given the impression of a condemned gladiator, and the [Cuban health] minister [Jose Ramon Machado Ventura], in passing on your optimistic message, confirmed the opinion that you were forming.

You will be able to speak at length with the bearer of this letter who will tell you his firsthand impressions after visiting much of the front; for this reason I will dispense with anecdotes. I will just say to you that, according to people close to me here, I have lost my reputation for objectivity by maintaining a groundless optimism in the face of the actual situation. I can assure you that were it not for me, this fine dream would have collapsed with catastrophe all around.

In my previous letters, I asked to be sent not many people but cadres; there is no real lack of arms here (except for special weapons) — indeed there are too many armed men; what is lacking are soldiers. I especially warned that no more money should be given out unless it was with a dropper and after many requests. None of what I said has been heeded, and fantastic plans have been made which threaten to discredit us internationally and may land me in a very difficult position.

I shall now explain to you.

Soumialot [Gaston Soumialot, president of the Supreme Council of the Revolution] and his comrades have been leading you all right up the garden path. It would be tedious to list the huge number of lies they have spun. There are two zones where something of an organised revolution exists — the one where we ourselves are, and part of Kasai province (the great unknown quantity) where Mulele [Pierre Mulele, former minister under Lumumba and the first leader to take up arms] is based.

In the rest of the country there are bands living in the forest, not connected to one another; they lost everything without a fight, as they lost Stanleyville without a fight. More serious than this, however, is the way in which the groups in this area (the only one with contacts to the outside) relate to one another.

The dissensions between Kabila [then second vice-president of the Supreme Council of the Revolution and head of the eastern front where Guevara was] and Soumialot are becoming more serious all the time, and are used as a pretext to keep handing towns over without a fight. I know Kabila well enough not to have any illusions about him. I cannot say the same about Soumialot, but I have some indications such as the string of lies he has been feeding you, the fact that he does not deign to come to these godforsaken parts, his frequent bouts of drunkenness in Dar es Salaam, where he lives in the best hotels, and the kind of people he has as allies here against the other group.

Recently a group from the Tshombist [pro-government] army landed, in the Baraka area (where a major-general loyal to Soumialot has no fewer than a thousand armed men) and captured this strategically important place almost without a fight. Now they are arguing about who was to blame — those who did not put up a fight, or those at the lake who did not send enough ammunition. The fact is that they shamelessly ran away, ditching in the open a 75mm recoilless gun and two 82 mortars; all the men assigned to these weapons have disappeared, and now they are asking me for Cubans to get them back from wherever they are (no one quite knows where) and to use them in battle.

Nor are they doing anything to defend Fizi, 36km from here; they don’t want to dig trenches on the only access road through the mountains. This will give you a faint idea of the situation. As for the need to choose men well rather than send me large numbers, you and the commissar assure me that the men here are good; I’m sure most of them are — otherwise they’d have quit long ago. But that’s not the point. You have to be really well tempered to put up with the things that happen here. It’s not good men but supermen that are needed…

And there are still my 200; believe me, they would do more harm than good at the present time — unless we decide once and for all to fight alone, in which case we’ll need a division and we’ll have to see how many the enemy put up against us. Maybe that’s a bit of an exaggeration; maybe a battalion would be enough to get back to the frontiers we had when we arrived here and to threaten Albertville.

But numbers are not what matters; we can’t liberate by ourselves a country that does not want to fight; you’ve got to create a fighting spirit and look for soldiers with the torch of Diogenes and the patience of Job — a task that becomes more difficult, the more shits there are doing things along the way.

The business with the money is what hurts me most, after all the warnings I gave. At the height of my «spending spree» and only after they had kicked up a lot of fuss, I undertook to supply one front (the most important one) on condition that I would direct the struggle and form a special mixed column under my direct command, in accordance with the strategy that I outlined and communicated to you.

With a very heavy heart, I calculated that it would require $5,000 a month. Now I learn that a sum 20 times higher is given to people who pass through just once, so that they can live well in all the capitals of the African world, with no allowance for the fact that they receive free board and lodging and often their travel costs from the main progressive countries. Not a cent will reach a wretched front where the peasants suffer every misery you can imagine, including the rapaciousness of their own protectors; nor will anything get through to the poor devils stuck In Sudan. (Whisky and women are not on the list of expenses covered by friendly governments, and they cost a lot if you want quality.)

Finally, 50 doctors will give the liberated area of the Congo an enviable proportion of one per thousand inhabitants — a level surpassed only by the USSR, the United States and two or three of the most advanced countries in the world. But no allowance is made for the fact that here they are

distributed according to political preference, without a trace of public health organisation. Instead of such gigantism, it would be better to send a contingent of revolutionary doctors and to increase it as I request, along with highly practical nurses of a similar kind.

As the attached map sums up the military situation, I shall limit myself to a few recommendations that I would ask you all to consider objectively: forget all the men in charge of phantom groups; train up to a hundred cadres (not necessarily all blacks)… As for weapons: the new bazooka, percussion caps with their own power supply, a few R-4s and nothing else for the moment; forget about rifles, which won’t solve anything unless they are electronic. Our mortars must be in Tanzania, and with those plus a new complement of men to operate them we would have more than enough for now. Forget about Burundi and tactfully discuss the question of the launches. (Don’t forget that Tanzania is an independent country and we’ve got to play it fair there, leaving aside the little problem I caused.)

Send the mechanics as soon as possible, as well as someone who can steer across the lake reasonably safely; that has been discussed and Tanzania has agreed. Leave me to handle the problem of the doctors, which I will do by giving some of them to Tanzania. Don’t make the mistake again of dishing out money like that; for they cling to me when they feel hard up and certainly won’t pay me any attention if the money is flowing freely. Trust my judgment a little and don’t go by appearances. Shake the representatives into giving truthful information, because they are not capable of figuring things out and present utopian pictures which have nothing to do with reality.

I have tried to be explicit and objective, synthetic and truthful. Do you believe me?

Warm greetings,

CHE

Che Guevara speech in Algiers (Afro-Asian Conference 1965)

Η παρακάτω ομιλία εκφωνήθηκε από τον Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα κατά το δεύτερο Οικονομικό Συμπόσιο της Αφρο-Ασιατικής Αλληλεγγύης. Η Σύνοδος έλαβε χώρα στην πρωτεύουσα της Αλγερίας και μετείχαν αντιπρόσωποι 63 Αφρικανικών και Ασιατικών κυβερνήσεων όπως επίσης και 19 εθνικοαπελευθερωτικά Κινήματα απ’ όλον τον κόσμο. Η Κούβα προσκλήθηκε ως παρατηρητής της Συνόδου και ο Τσε μετείχε της προεδρικής επιτροπής αυτής.

Η παρακάτω ομιλία εκφωνήθηκε από τον Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα κατά το δεύτερο Οικονομικό Συμπόσιο της Αφρο-Ασιατικής Αλληλεγγύης. Η Σύνοδος έλαβε χώρα στην πρωτεύουσα της Αλγερίας και μετείχαν αντιπρόσωποι 63 Αφρικανικών και Ασιατικών κυβερνήσεων όπως επίσης και 19 εθνικοαπελευθερωτικά Κινήματα απ’ όλον τον κόσμο. Η Κούβα προσκλήθηκε ως παρατηρητής της Συνόδου και ο Τσε μετείχε της προεδρικής επιτροπής αυτής.

Cuba is here at this conference to speak on behalf of the peoples of Latin America.As we have emphasized on other occasions, Cuba also speaks as an underdeveloped country as well as one that is building socialism.

It is not by accident that our delegation is permitted to give its opinion here, in the circle of the peoples of Asia and Africa.A common aspiration unites us in our march toward the future: the defeat of imperialism. A common past of struggle against the same enemy has united us along the road.

This is an assembly of peoples in struggle, and the struggle is developing on two equally important fronts that require all our efforts. The struggle against imperialism, for liberation from colonial or neocolonial shackles, which is being carried out by means of political weapons, arms, or a combination of the two, is not separate from the struggle against backwardness and poverty. Both are stages on the same road leading toward the creation of a new society of justice and plenty.

It is imperative to take political power and to get rid of the oppressor classes. But then the second stage of the struggle, which may be even more difficult than the first, must be faced.

Ever since monopoly capital took over the world, it has kept the greater part of humanity in poverty, dividing all the profits among the group of the most powerful countries. The standard of living in those countries is based on the extreme poverty of our countries. To raise the living standards of the underdeveloped nations, therefore, we must fight against imperialism. And each time a country is torn away from the imperialist tree, it is not only a partial battle won against the main enemy but it also contributes to the real weakening of that enemy, and is one more step toward the final victory. There are no borders in this struggle to the death. We cannot be indifferent to what happens anywhere in the world, because a victory by any country over imperialism is our victory, just as any country’s defeat is a defeat for all of us. The practice of proletarian internationalism is not only a duty for the peoples struggling for a better future, it is also an inescapable necessity.

If the imperialist enemy, the United States or any other, carries out its attack against the underdeveloped peoples and the socialist countries, elementary logic determines the need for an alliance between the underdeveloped peoples and the socialist countries. If there were no other uniting factor, the common enemy should be enough.

Of course, these alliances cannot be made spontaneously, without discussions, without birth pangs, which sometimes can be painful. We said that each time a country is liberated it is a defeat for the world imperialist system. But we must agree that the break is not achieved by the mere act of proclaiming independence or winning an armed victory in a revolution. It is achieved when imperialist economic domination over a people is brought to an end. Therefore, it is a matter of vital interest to the socialist countries for a real break to take place. And it is our international duty, a duty determined by our guiding ideology, to contribute our efforts to make this liberation as rapid and deep-going as possible.

A conclusion must be drawn from all this: the socialist countries must help pay for the development of countries now starting out on the road to liberation. We state it this way with no intention whatsoever of blackmail or dramatics, nor are we looking for an easy way to get closer to the Afro- Asian peoples; it is our profound conviction. Socialism cannot exist without a change in consciousness resulting in a new fraternal attitude toward humanity, both at an individual level, within the societies where socialism is being built or has been built, and on a world scale, with regard to all peoples suffering from imperialist oppression.

We believe the responsibility of aiding dependent countries must be approached in such a spirit. There should be no more talk about developing mutually beneficial trade based on prices forced on the backward countries by the law of value and the international relations of unequal exchange that result from the law of value.How can it be “mutually beneficial” to sell at world market prices the raw materials that cost the underdeveloped countries immeasurable sweat and suffering, and to buy at world market prices the machinery produced in today’s big automated factories?

If we establish that kind of relation between the two groups of nations, we must agree that the socialist countries are, in a certain way, accomplices of imperialist exploitation. It can be argued that the amount of exchange with the underdeveloped countries is an insignificant part of the foreign trade of the socialist countries. That is very true, but it does not eliminate the immoral character of that exchange.

The socialist countries have the moral duty to put an end to their tacit complicity with the exploiting countries of the West. The fact that the trade today is small means nothing. In 1959 Cuba only occasionally sold sugar to some socialist bloc countries, usually through English brokers or brokers of other nationalities. Today 80 percent of Cuba’s trade is with that area. All its vital supplies come from the socialist camp, and in fact it has joined that camp. We cannot say that this entrance into the socialist camp was brought about merely by the increase in trade. Nor was the increase in trade brought about by the destruction of the old structures and the adoption of the socialist form of development. Both sides of the question intersect and are interrelated.

We did not start out on the road that ends in communism foreseeing all steps as logically predetermined by an ideology advancing toward a fixed goal. The truths of socialism, plus the raw truths of imperialism, forged our people and showed them the path that we have now taken consciously. To advance toward their own complete liberation, the peoples of Asia and Africa must take the same path. They will follow it sooner or later, regardless of what modifying adjective their socialism may take today.

For us there is no valid definition of socialism other than the abolition of the exploitation of one human being by another. As long as this has not been achieved, if we think we are in the stage of building socialism but instead of ending exploitation the work of suppressing it comes to a halt — or worse, is reversed — then we cannot even speak of building socialism.We have to prepare conditions so that our brothers and sisters can directly and consciously take the path of the complete abolition of exploitation, but we cannot ask them to take that path if we ourselves are accomplices in that exploitation. If we were asked what methods are used to establish fair prices, we could not answer because we do not know the full scope of the practical problems involved. All we know is that, after political discussions, the Soviet Union and Cuba have signed agreements advantageous to us, by means of which we will sell five million tons of sugar at prices set above those of the so-called free world sugar market. The People’s Republic of China also pays those prices in buying from us.

This is only a beginning. The real task consists of setting prices that will permit development. A great shift in ideas will be involved in changing the order of international relations. Foreign trade should not determine policy, but should, on the contrary, be subordinated to a fraternal policy toward the peoples. Let us briefly analyze the problem of long-term credits for developing basic industries. Frequently we find that beneficiary countries attempt to establish an industrial base disproportionate to their present capacity. The products will not be consumed domestically and the country’s reserves will be risked in the undertaking.

Our thinking is as follows: The investments of the socialist states in their own territory come directly out of the state budget, and are recovered only by use of the products throughout the entire manufacturing process, down to the finished goods. We propose that some thought be given to the possibility of making these kinds of investments in the underdeveloped countries. In this way we could unleash an immense force, hidden in our continents, which have been exploited miserably but never aided in their development. We could begin a new stage of a real international division of labor, based not on the history of what has been done up to now but rather on the future history of what can be done.

The states in whose territories the new investments are to be made would have all the inherent rights of sovereign property over them with no payment or credit involved. But they would be obligated to supply agreed-upon quantities of products to the investor countries for a certain number of years at set prices.

The method for financing the local portion of expenses incurred by a country receiving investments of this kind also deserves study. The supply of marketable goods on long-term credits to the governments of underdeveloped countries could be one form of aid not requiring the contribution of freely convertible hard currency. Another difficult problem that must be solved is the mastering of technology. The shortage of technicians in underdeveloped countries is well known to us all. Educational institutions and teachers are lacking. Sometimes we lack a real understanding of our needs and have not made the decision to carry out a top-priority policy of technical, cultural and ideological development.

The socialist countries should supply the aid to organize institutions for technical education. They should insist on the great importance of this and should supply technical cadres to fill the present need. It is necessary to further emphasize this last point. The technicians who come to our countries must be exemplary. They are comrades who will face a strange environment, often one hostile to technology, with a different language and totally different customs. The technicians who take on this difficult task must be, first of all, communists in the most profound and noble sense of the word. With this single quality, plus a modicum of flexibility and organization, wonders can be achieved. We know this can be done. Fraternal countries have sent us a certain number of technicians who have done more for the development of our country than 10 institutes, and have contributed more to our friendship than 10 ambassadors or 100 diplomatic receptions.

If we could achieve the above-listed points — and if all the technology of the advanced countries could be placed within reach of the underdeveloped countries, unhampered by the present system of patents, which prevents the spread of inventions of different countries — we would progress a great deal in our common task. Imperialism has been defeated in many partial battles. But it remains a considerable force in the world. We cannot expect its final defeat save through effort and sacrifice on the part of us all.

The proposed set of measures, however, cannot be implemented unilaterally. The socialist countries should help pay for the development of the underdeveloped countries, we agree. But the underdeveloped countries must also steel their forces to embark resolutely on the road of building a new society — whatever name one gives it — where the machine, an instrument of labor, is no longer an instrument for the exploitation of one human being by another. Nor can the confidence of the socialist countries be expected by those who play at balancing between capitalism and socialism, trying to use each force as a counterweight in order to derive certain advantages from such competition. A new policy of absolute seriousness should govern the relations between the two groups of societies. It is worth emphasizing once again that the means of production should preferably be in the hands of the state, so that the marks of exploitation may gradually disappear. Furthermore, development cannot be left to complete improvisation. It is necessary to plan the construction of the new society. Planning is one of the laws of socialism, and without it, socialism would not exist. Without correct planning there can be no adequate guarantee that all the various sectors of a country’s economy will combine harmoniously to take the leaps forward that our epoch demands.

Planning cannot be left as an isolated problem of each of our small countries, distorted in their development, possessors of some raw materials or producers of some manufactured or semimanufactured goods, but lacking in most others.[25] From the outset, planning should take on a certain regional dimension in order to intermix the various national economies, and thus bring about integration on a basis that is truly of mutual benefit. We believe the road ahead is full of dangers, not dangers conjured up or foreseen in the distant future by some superior mind but palpable dangers deriving from the realities besetting us. The fight against colonialism has reached its final stages, but in the present era colonial status is only a consequence of imperialist domination. As long as imperialism exists it will, by definition, exert its domination over other countries. Today that domination is called neocolonialism.

Neocolonialism developed first in South America, throughout a whole continent, and today it begins to be felt with increasing intensity in Africa and Asia. Its forms of penetration and development have different characteristics. One is the brutal form we have seen in the Congo. Brute force, without any respect or concealment whatsoever, is its extreme weapon. There is another more subtle form: penetration into countries that win political independence, linking up with the nascent local bourgeoisies, development of a parasitic bourgeois class closely allied to the interests of the former colonizers. This development is based on a certain temporary rise in the people’s standard of living, because in a very backward country the simple step from feudal to capitalist relations marks a big advance, regardless of the dire consequences for the workers in the long run.

Neocolonialism has bared its claws in the Congo. That is not a sign of strength but of weakness. It had to resort to force, its extreme weapon, as an economic argument, which has generated very intense opposing reactions. But at the same time a much more subtle form of neocolonialism is being practiced in other countries of Africa and Asia. It is rapidly bringing about what some have called the South Americanization of these continents; that is, the development of a parasitic bourgeoisie that adds nothing to the national wealth of their countries but rather deposits its huge ill-gotten profits in capitalist banks abroad, and makes deals with foreign countries to reap more profits with absolute disregard for the welfare of the people. There are also other dangers, such as competition between fraternal countries, which are politically friendly and sometimes neighbors, as both try to develop the same investments simultaneously to produce for markets that often cannot absorb the increased volume. This competition has the disadvantage of wasting energies that could be used to achieve much greater economic coordination; furthermore, it gives the imperialist monopolies room to maneuver.

When it has been impossible to carry out a given investment project with the aid of the socialist camp, there have been occasions when the project has been accomplished by signing agreements with the capitalists. Such capitalist investments have the disadvantage not only of the terms of the loans but other, much more important disadvantages as well, such as the establishment of joint ventures with a dangerous neighbor. Since these investments in general parallel those made in other states, they tend to cause divisions between friendly countries by creating economic rivalries. Furthermore, they create the dangers of corruption flowing from the constant presence of capitalism, which is very skillful in conjuring up visions of advancement and well-being to fog the minds of many people. Some time later, prices drop in the market saturated by similar products. The affected countries are obliged to seek new loans, or to permit additional investments in order to compete. The final consequences of such a policy are the fall of the economy into the hands of the monopolies, and a slow but sure return to the past. As we see it, the only safe method for investments is direct participation by the state as the sole purchaser of the goods, limiting imperialist activity to contracts for supplies and not letting them set one foot inside our house. And here it is just and proper to take advantage of interimperialist contradictions in order to secure the least burdensome terms.

We have to watch out for “disinterested” economic, cultural and other aid that imperialism grants directly or through puppet states, which gets a better reception in some parts of the world.

If all of these dangers are not seen in time, some countries that began their task of national liberation with faith and enthusiasm may find themselves on the neocolonial road, as monopoly domination is subtly established step by step so that its effects are difficult to discern until they brutally make themselves felt.

There is a big job to be done. Immense problems confront our two worlds — that of the socialist countries and that called the Third World — problems directly concerning human beings and their welfare, and related to the struggle against the main force that bears the responsibility for our backwardness. In the face of these problems, all countries and peoples conscious of their duties, of the dangers involved in the situation, of the sacrifices required by development, must take concrete steps to cement our friendship in the two fields that can never be separated: the economic and the political. We should organize a great solid bloc that, in its turn, helps new countries to free themselves not only from the political power of imperialism but also from its economic power.

The question of liberation by armed struggle from an oppressor political power should be dealt with in accordance with the rules of proletarian internationalism. In a socialist country at war, it would be absurd to conceive of a factory manager demanding guaranteed payment before shipping to the front the tanks produced by his factory. It ought to seem no less absurd to inquire of a people fighting for liberation, or needing arms to defend its freedom, whether or not they can guarantee payment.

Arms cannot be commodities in our world. They must be delivered to the peoples asking for them to use against the common enemy, with no charge and in the quantities needed and available. That is the spirit in which the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China have offered us their military aid. We are socialists; we constitute a guarantee of the proper utilization of those arms. But we are not the only ones, and all of us should receive the same treatment. The reply to the ominous attacks by U.S. imperialism against Vietnam or the Congo should be to supply those sister countries with all the defense equipment they need, and to offer them our full solidarity without any conditions whatsoever.

In the economic field we must conquer the road to development with the most advanced technology possible. We cannot set out to follow the long ascending steps from feudalism to the nuclear and automated era. That would be a road of immense and largely useless sacrifice. We have to start from technology at its current level. We have to make the great technological leap forward that will reduce the current gap between the more developed countries and ourselves. Technology must be applied to the large factories and also to a properly developed agriculture. Above all, its foundation must be technological and ideological education, with a sufficient mass base and strength to sustain the research institutes and organizations that have to be created in each country, as well as the men and women who will use the existing technology and be capable of adapting themselves to the newly mastered technology.

These cadres must have a clear awareness of their duty to the society in which they live. There cannot be adequate technological education if it is not complemented by ideological education; without technological education, in most of our countries, there cannot be an adequate foundation for industrial development, which is what determines the development of a modern society, or the most basic consumer goods and adequate schooling. A good part of the national revenues must be spent on so-called unproductive investment in education. And priority must be given to the development of agricultural productivity. The latter has reached truly incredible levels in many capitalist countries, producing the senseless crisis of overproduction and a surplus of grain and other food products or industrial raw materials in the developed countries. While the rest of the world goes hungry, these countries have enough land and labor to produce several times over what is needed to feed the entire world. Agriculture must be considered a fundamental pillar of our development. Therefore, a fundamental aspect of our work should be changes in the agrarian structure, and adaptation to the new technological possibilities and to the new obligations of eliminating the exploitation of human beings.

Before making costly decisions that could cause irreparable damage, a careful survey of the national territory is needed. This is one of the preliminary steps in economic research and a basic prerequisite for correct planning. We warmly support Algeria’s proposal for institutionalizing our relations. We would just like to make some supplementary suggestions: First: in order for the union to be an instrument in the struggle against imperialism, the cooperation of Latin American countries and an alliance with the socialist countries is necessary.

Second: we should be vigilant in preserving the revolutionary character of the union, preventing the admission into it of governments or movements not identified with the general aspirations of the people, and creating mechanisms that would permit the separation from it of any government or popular movement diverging from the just road.

Third: we must advocate the establishment of new relations on an equal footing between our countries and the capitalist ones, creating a revolutionary jurisprudence to defend ourselves in case of conflict, and to give new meaning to the relations between ourselves and the rest of the world. We speak a revolutionary language and we fight honestly for the victory of that cause. But frequently we entangle ourselves in the nets of an international law created as the result of confrontations between the imperialist powers, and not by the free peoples, the just peoples, in the course of their struggles.

For example, our peoples suffer the painful pressure of foreign bases established on their territories, or they have to carry the heavy burden of massive foreign debts. The story of these throwbacks is well known to all of us. Puppet governments, governments weakened by long struggles for liberation or the operation of the laws of the capitalist market, have allowed treaties that threaten our internal stability and jeopardize our future. Now is the time to throw off the yoke, to force renegotiation of oppressive foreign debts, and to force the imperialists to abandon their bases of aggression. I would not want to conclude these remarks, this recitation of concepts you all know, without calling the attention of this gathering to the fact that Cuba is not the only Latin American country; it is simply the only one that has the opportunity of speaking before you today. Other peoples are shedding their blood to win the rights we have. When we send our greetings from here, and from all the conferences and the places where they may be held, to the heroic peoples of Vietnam, Laos, so-called Portuguese Guinea, South Africa, or Palestine — to all exploited countries fighting for their emancipation — we must simultaneously extend our voice of friendship, our hand and our encouragement, to our fraternal peoples in Venezuela, Guatemala and Colombia, who today, arms in hand, are resolutely saying “No!” to the imperialist enemy.

Few settings from which to make this declaration are as symbolic as Algiers, one of the most heroic capitals of freedom. May the magnificent Algerian people — schooled as few others in sufferings for independence, under the decisive leadership of its party, headed by our dear compañero Ahmed Ben Bella — serve as an inspiration to us in this fight without quarter against world imperialism.

(Πηγή: Διαδικτυακό Αρχείο Μαρξιστών – © 2005 Aleida March, Che Guevara Studies Center and Ocean Press. Reprinted with their permission. Not to be reproduced in any form without the written permission of Ocean Press)

Che Guevara in Search of a New Socialism

By Michael Löwy*.

By Michael Löwy*.

IN AN ARTICLE published in 1928, José Carlos Mariátegui, the true founder of Latin American Marxism, wrote: “Of course, we do not want socialism in Latin America to be an imitation or a copy. It must be a heroic creation. We must inspire Indo-American socialism with our own reality, our own language. That is a mission worthy of a new generation.” [1] His warning went unheard. In that same year the Latin American communist movement fell under the influence of the Stalinist paradigm, which for close to a half century imposed on it an imitation of the ideology of the Soviet bureaucracy and its so-called “actually existing socialism.”

We do not know whether Ernesto “Che” Guevara was acquainted with Mariátegui’s article. He may have read it, for his companion Hilda Gadea loaned him Mariátegui’s writings in the years preceding the Cuban revolution. Whatever the case, much of his political thought and practice, especially in the 1960s, can be said to have been aimed at emerging from the impasse to which the servile imitation of the Soviet model had led in Eastern Europe.

Che’s ideas on the construction of socialism are an attempt at “heroic creation” of something new, the search — interrupted and incomplete — for a distinct model of socialism, radically opposed in many respects to the “actually existing” bureaucratic caricature.

From 1959 to 1967, Che’s thought evolved considerably. He distanced himself ever further from his initial illusions concerning Soviet or Soviet-style socialism, that is, from the Stalinist version of Marxism. In a 1965 letter to a Cuban friend, he harshly criticized the “ideological tailism” that was manifested in Cuba by the publication of Soviet manuals for instruction in Marxism. These manuals, “Soviet bricks” to use his expression, “have the disadvantage of not letting you think: the Party has already done it for you and you have to digest it.” [2]

Still more explicit, especially in his post-1963 writings, is his rejection of “imitation and copy” and his search for an alternative model, his attempt to formulate another path toward socialism, one that is more radical, more egalitarian, more fraternal, and more consistent with the communist ethic.

An Uncompleted Journey

Che’s death in October 1967 interrupted a process of independent political maturation and intellectual development. His work is not a closed system, a polished system of thought with an answer to everything. On many questions, such as planning, the struggle against bureaucracy, and so on, his thinking remains incomplete. [3]

The driving force behind this quest for a new road — over and above the specific economic issues — was the conviction that socialism is meaningless and consequently cannot triumph unless it holds out the offer of a civilization, a social ethic, a model of society that is totally antagonistic to the values of petty individualism, unfettered egoism, competition, the war of all against all that is characteristic of capitalist civilization, this world in which “man eats man.”

The construction of socialism for Che is inseparable from certain moral values, in contrast to the “economistic” conceptions of Stalin, Krushchev and their successors, who consider only the “development of the productive forces.” In a famous interview with the journalist Jean Daniel, in July 1963, Che was already developing an implicit critique of “actually existing socialism”: “Economic socialism without a communist morale does not interest me. We are fighting poverty, but at the same time alienation….If communism is dissociated from consciousness, it may be a method of distribution but it is no longer a revolutionary morality.” [4]

If socialism claims to fight capitalism and conquer it on its own ground, that of productivism and consumption, using the weapons of capitalism — the commodity form, competition, self-center individualism — it is doomed to failure. It cannot be said that Che anticipated the dismantling of the USSR, but in a way he did have the intuition that a “socialist” system that does not tolerate differences, that does not embody new values, that attempts to imitate its adversary, that has no ambitions but to “catch up to and surpass” the production of the imperialist metropolises, has no future.

Socialism, for Che, represented the historical project of a new society based on values of equality, solidarity, collectivism, revolutionary altruism, free discussion and mass participation. His increasing criticisms of “actually existing socialism,” like his practice as a leader and his thinking about the Cuban experience, were inspired by this communist utopia, in the sense given this concept by Ernst Bloch. [5]

Three things express in concrete terms this aspiration of Guevara and his search for a new path: the discussion on the methods of economic management, the question of the free expression of differences and the perspective of socialist democracy. The first clearly occupied a central place in Che’s thinking, while the other two, which are closely related, are much less developed, with some lacunae and contradictions. But they are ever-present in his concerns and his political practice.

The New Man

In his famous “Speech in Algiers” in February 1965, Ernesto Guevara called on the countries claiming to be socialist to “put an end to their implicit complicity with the exploiting countries of the West” as expressed in the unequal exchange relationships they were carrying on with peoples engaged in struggle against imperialism. Socialism, in Che’s view, “cannot exist without a change in consciousness to a new fraternal attitude toward humanity, not only within the societies which are building or have built socialism, but also on a world scale toward all peoples suffering from imperialist oppression.” [6]

In his March 1965 essay, “Socialism and Man in Cuba,” analyzing the models for building socialism that were applied in Eastern Europe, Che rejected the conception that claimed to “conquer capitalism with its own fetishes.” “The pipe dream that socialism can be achieved with the help of the dull instruments bequeathed to us by capitalism (the commodity as the economic cell, profitability, individual material interest as a lever and so on) can lead into a blind alley….To build communism it is necessary, simultaneous with the new material foundations, to build the new man.” [7]

One of the major dangers in the model imported from the countries of Eastern Europe was the increase in social inequality and the formation of a privileged layer of technocrats and bureaucrats: in this system of remuneration, “it is the directors who always earn more. Just look at the recent proposal in the German Democratic Republic; the importance assigned to management by the director, or what’s more the director’s remuneration for managing.” [8]

Basically, the debate was a confrontation between an “economistic” view, which considered the economic sphere as an autonomous system governed by its own laws like the law of value or the laws of the market, and a political conception of socialism, in which economic decisions concerning production priorities, prices, and so on are governed by social, ethical, and political criteria.

Che’s economic proposals — planning in opposition to market forces, the budgetary finance system, collective or “moral” incentives — were attempts to find a model for building socialism based on these criteria, and thus differing from the Soviet model. It should be added that Guevara did not successfully develop a clear idea of the nature of the Stalinist bureaucratic system. In my opinion, he was mistaken in tracing the origin of the problems and limitations of the Soviet experience to the NEP rather than the Stalinist Thermidor. [9]

NOTES

[1] J. C. Mariátegui, “Aniversario y balance,” Ideología y Política, Biblioteca Amauta, 1971): 249. José Carlos Mariátegui (1894–1930) was one of the major Marxist thinkers of Latin America. He is primarily known for his 1928 work, Seven Interpretive Essays on Peruvian Reality (Austin: University of Texas, Austin, 1971).

[2] Letter from Che to a Cuban friend (1965). This letter is one of Che’s documents that remain unpublished. Carlos Tablada quotes from it in his article “Le marxisme d’Ernesto (Che) Guevara,” Alternatives Sud III, no. 2 (1996):168. See also, by the same author, Che Guevara: Economics and Politics in the Transition to Socialism (Pathfinder Press, 1992) and Cuba, quelle transition? (L’Harmattan, 2001).

[3] Fernando Martínez Heredia correctly notes that “… there are even some positive aspects to the incomplete nature of Che’s thinking. The great thinker is there, points to some problems and some approaches, shows some possibilities, and demands that his comrades think, study, and combine practice and theory. It becomes impossible, once one really comes to terms with his thought, to dogmatize it and transform it into a speculative bastion or a receptacle of slogans.” “Che, el socialismo y el comunismo,” Pensar el Che, (Havana: Centro de estudios sobre América, Editorial José Martí, vol. II, 1989): 30. See also Fernando Martínez Heredia, Che, el socialismo y el comunismo (Havana: Casa de las Américas prize, 1989).

[4] L’Express, July 25, 1963, 9.

[5] Ernst Bloch (1885-1977) was a Jewish-German philosopher exiled to the United States in 1938 . He became a professor at Karl Marx University in Leipzig in 1949, and at the University of Tübingen after going over to the West in 1961. From The Spirit of Utopia (1918) to The Principle of Hope (1954-1959), this unorthodox Marxist sought to restore to socialism its secular messianic dimension.

[6] Ernesto Che Guevara, Oeuvres 1957-1967, vol. 2 (Paris: François Maspero, 1971): 574.

[7] Guevara, Oeuvres, vol. 2, 371–372.

[8] Ernesto Che Guevara, “Le plan et les hommes,” Oeuvres 1957–1967, vol. 6 [unedited text] (Paris: Maspero, 1972): 90.

[9] This concept is very clear in the essay on political economy that Che wrote in 1966, from which Carlos Tablada quotes certain extracts in “Le marxisme d’Ernesto (Che) Guevara.” Janette Habel rightly observes that Guevara put “too much emphasis, in the economic criticism of Stalinist deformations, on the weight of market relations and not enough on the police and repressive nature of the Soviet political system.” (J. Habel, preface to M. Löwy, La pensée de Che Guevara (Paris: Syllepse, 1997): 11.

* Michael Löwy is a French philosopher and sociologist of Brazilian origin. A Fellow of the IIRE in Amsterdam and former research director of the French National Council for Scientific Research (CNRS), he has written many books, including The Marxism of Che Guevara, Marxism and Liberation Theology, Fatherland or Mother Earth? and The War of Gods: Religion and Politics in Latin America. Löwy is a member of the New Anti-capitalist Party in France.

Οι απόψεις που εκφράζονται στο άρθρο δεν υιοθετούνται απ’ το Ελληνικό Αρχείο Τσε Γκεβάρα.

El socialismo y el hombre en Cuba

Estimado compañero *:

Estimado compañero *:

Acabo estas notas en viaje por África, animado del deseo de cumplir, aunque tardíamente, mi promesa. Quisiera hacerlo tratando el tema del título. Creo que pudiera ser interesante para los lectores uruguayos.

Es común escuchar de boca de los voceros capitalistas, como un argumento en la lucha ideológica contra el socialismo, la afirmación de que este sistema social o el período de construcción del socialismo al que estamos nosotros abocados, se caracteriza por la abolición del individuo en aras del Estado. No pretenderé refutar esta afirmación sobre una base meramente teórica, sino establecer los hechos tal cual se viven en Cuba y agregar comentarios de índole general. Primero esbozaré a grandes rasgos la historia de nuestra lucha revolucionaria antes y después de la toma del poder.

Como es sabido, la fecha precisa en que se iniciaron las acciones revolucionarias que culminaron el primero de enero de 1959, fue el 26 de julio de 1953. Un grupo de hombres dirigidos por Fidel Castro atacó la madrugada de ese día el cuartel Moncada, en la provincia de Oriente. El ataque fue un fracaso, el fracaso se transformó en desastre y los sobrevivientes fueron a parar a la cárcel, para reiniciar, luego de ser amnistiados, la lucha revolucionaria.

Durante este proceso, en el cual solamente existían gérmenes de socialismo, el hombre era un factor fundamental. En él se confiaba, individualizado, específico, con nombre y apellido, y de su capacidad de acción dependía el triunfo o el fracaso del hecho encomendado.

Llego la etapa de la lucha guerrillera. Esta se desarrolló en dos ambientes distintos: el pueblo, masa todavía dormida a quien había que movilizar y su vanguardia, la guerrilla, motor impulsor de la movilización, generador de conciencia revolucionaria y de entusiasmo combativo. Fue esta vanguardia el agente catalizador, el que creó las condiciones subjetivas necesarias para la victoria. También en ella, en el marco del proceso de proletarización de nuestro pensamiento, de la revolución que se operaba en nuestros hábitos, en nuestras mentes, el individuo fue el factor fundamental. Cada uno de los combatientes de la Sierra Maestra que alcanzara algún grado superior en las fuerzas revolucionarias, tiene una historia de hechos notables en su haber. En base a estos lograba sus grados.

Fue la primera época heroica, en la cual se disputaban por lograr un cargo de mayor responsabilidad, de mayor peligro, sin otra satisfacción que el cumplimiento del deber. En nuestro trabajo de educación revolucionaria, volvemos a menudo sobre este tema aleccionador. En la actitud de nuestros combatientes se vislumbra al hombre del futuro.

En otras oportunidades de nuestra historia se repitió el hecho de la entrega total a la causa revolucionaria. Durante la Crisis de Octubre o en los días del ciclón Flora, vimos actos de valor y sacrificio excepcionales realizados por todo un pueblo. Encontrar la fórmula para perpetuar en la vida cotidiana esa actitud heroica, es una de nuestras tareas fundamentales desde el punto de vista ideológico.

En enero de 1959 se estableció el gobierno revolucionario con la participación en él de varios miembros de la burguesía entreguista. La presencia del Ejército Rebelde constituía la garantía de poder, como factor fundamental de fuerza.

Se produjeron enseguida contradicciones seria, resueltas, en primera instancia, en febrero del 59, cuando Fidel Castro asumió la jefatura de gobierno con el cargo de primer ministro. Culminaba el proceso en julio del mismo año, al renunciar el presidente Urrutia ante la presión de las masas.

Aparecía en la historia de la Revolución Cubana, ahora con caracteres nítidos, un personaje que se repetirá sistemáticamente: la masa.

Este ente multifacético no es, como se pretende, la suma de elementos de la misma categoría (reducidos a la misma categoría, además, por el sistema impuesto), que actúa como un manso rebaño. Es verdad que sigue sin vacilar a sus dirigentes, fundamentalmente a Fidel Castro, pero el grado en que él ha ganado esa confianza responde precisamente a la interpretación cabal de los deseos del pueblo, de sus aspiraciones, y a la lucha sincera por el cumplimiento de las promesas hechas.

La masa participó en la reforma agraria y en el difícil empeño de la administración de las empresas estatales; pasó por la experiencia heroica de Playa Girón; se forjó en las luchas contra las distintas bandas de bandidos armadas por la CIA; vivió una de las definiciones más importantes de los tiempos modernos en la Crisis de Octubre y sigue hoy trabajando en la construcción del socialismo.

Vistas las cosas desde un punto de vista superficial, pudiera parecer que tienen razón aquellos que hablan de supeditación del individuo al Estado, la masa realiza con entusiasmo y disciplina sin iguales las tareas que el gobierno fija, ya sean de índole económica, cultural, de defensa, deportiva, etcétera. La iniciativa parte en general de Fidel o del alto mando de la revolución y es explicada al pueblo que la toma como suya. Otras veces, experiencias locales se toman por el partido y el gobierno para hacerlas generales, siguiendo el mismo procedimiento.

Sin embargo, el Estado se equivoca a veces. Cuando una de esas equivocaciones se produce, se nota una disminución del entusiasmo colectivo por efectos de una disminución cuantitativa de cada uno de los elementos que la forman, y el trabajo se paraliza hasta quedar reducido a magnitudes insignificantes; es el instante de rectificar. Así sucedió en marzo de 1962 ante una política sectaria impuesta al partido por Aníbal Escalante.

Es evidente que el mecanismo no basta para asegurar una sucesión de medidas sensatas y que falta una conexión más estructurada con las masas. Debemos mejorarla durante el curso de los próximos años pero, en el caso de las iniciativas surgidas de estratos superiores del gobierno utilizamos por ahora el método casi intuitivo de auscultar las reacciones generales frente a los problemas planteados.

Maestro en ello es Fidel, cuyo particular modo de integración con el pueblo solo puede apreciarse viéndolo actuar. En las grandes concentraciones públicas se observa algo así como el diálogo de dos diapasones cuyas vibraciones provocan otras nuevas en el interlocutor. Fidel y la masa comienzan a vibrar en un diálogo de intensidad creciente hasta alcanzar el clímax en un final abrupto, coronado por nuestro grito de lucha y victoria.

Lo difícil de entender, para quien no viva la experiencia de la revolución, es esa estrecha unidad dialéctica existente entre el individuo y la masa, donde ambos se interrelacionan y, a su vez, la masa, como conjunto de individuos, se interrelaciona con los dirigentes.

En el capitalismo se pueden ver algunos fenómenos de este tipo cuando aparecen políticos capaces de lograr la movilización popular, pero si no se trata de un auténtico movimiento social, en cuyo caso no es plenamente lícito hablar de capitalismo, el movimiento vivirá lo que la vida de quien lo impulse o hasta el fin de las ilusiones populares, impuesto por el rigor de la sociedad capitalista. En esta, el hombre está dirigido por un frío ordenamiento que, habitualmente, escapa al dominio de la comprensión. El ejemplar humano, enajenado, tiene un invisible cordón umbilical que le liga a la sociedad en su conjunto: la ley del valor. Ella actúa en todos los aspectos de la vida, va modelando su camino y su destino.

Las leyes del capitalismo, invisibles para el común de las gentes y ciegas, actúan sobre el individuo sin que este se percate. Solo ve la amplitud de un horizonte que aparece infinito. Así lo presenta la propaganda capitalista que pretende extraer del caso Rockefeller —verídico o no—, una lección sobre las posibilidades de éxito. La miseria que es necesario acumular para que surja un ejemplo así y la suma de ruindades que conlleva una fortuna de esa magnitud, no aparecen en el cuadro y no siempre es posible a las fuerzas populares aclarar estos conceptos. (Cabría aquí la disquisición sobre cómo en los países imperialistas los obreros van perdiendo su espíritu internacional de clase al influjo de una cierta complicidad en la explotación de los países dependientes y cómo este hecho, al mismo tiempo, lima el espíritu de lucha de las masas en el propio país, pero ese es un tema que sale de la intención de estas notas.)

De todos modos, se muestra el camino con escollos que aparentemente, un individuo con las cualidades necesarias puede superar para llegar a la meta. El premio se avizora en la lejanía; el camino es solitario. Además, es una carrera de lobos: solamente se puede llegar sobre el fracaso de otros.

Intentaré, ahora, definir al individuo, actor de ese extraño y apasionante drama que es la construcción del socialismo, en su doble existencia de ser único y miembro de la comunidad.

Creo que lo más sencillo es reconocer su cualidad de no hecho, de producto no acabado. Las taras del pasado se trasladan al presente en la conciencia individual y hay que hacer un trabajo continuo para erradicarlas.

El proceso es doble, por un lado actúa la sociedad con su educación directa e indirecta, por otro, el individuo se somete a un proceso consciente de autoeducación.

La nueva sociedad en formación tiene que competir muy duramente con el pasado. Esto se hace sentir no solo en la conciencia individual en la que pesan los residuos de una educación sistemáticamente orientada al aislamiento del individuo, sino también por el carácter mismo de este período de transición con persistencia de las relaciones mercantiles. La mercancía es la célula económica de la sociedad capitalista; mientras exista, sus efectos se harán sentir en la organización de la producción y, por ende, en la conciencia.

En el esquema de Marx se concebía el período de transición como resultado de la transformación explosiva del sistema capitalista destrozado por sus contradicciones; en la realidad posterior se ha visto cómo se desgajan del árbol imperialista algunos países que constituyen ramas débiles, fenómeno previsto por Lenin. En estos, el capitalismo se ha desarrollado lo suficiente como para hacer sentir sus efectos, de un modo u otro, sobre el pueblo, pero no son sus propias contradicciones las que, agotadas todas las posibilidades, hacen saltar el sistema. La lucha de liberación contra un opresor externo, la miseria provocada por accidentes extraños, como la guerra, cuyas consecuencias hacen recaer las clases privilegiadas sobre los explotados, los movimientos de liberación destinados a derrocar regímenes neocoloniales, son los factores habituales de desencadenamiento. La acción consciente hace el resto.

En estos países no se ha producido todavía una educación completa para el trabajo social y la riqueza dista de estar al alcance de las masas mediante el simple proceso de apropiación. El subdesarrollo por un lado y la habitual fuga de capitales hacia países «civilizados» por otro, hacen imposible un cambio rápido y sin sacrificios. Resta un gran tramo a recorrer en la construcción de la base económica y la tentación de seguir los caminos trillados del interés material, como palanca impulsora de un desarrollo acelerado, es muy grande.

Se corre el peligro de que los árboles impidan ver el bosque. Persiguiendo la quimera de realizar el socialismo con la ayuda de las armas melladas que nos legara el capitalismo (la mercancía como célula económica, la rentabilidad, el interés material individual como palanca, etcétera), se puede llegar a un callejón sin salida. Y se arriba allí tras de recorrer una larga distancia en la que los caminos se entrecruzan muchas veces y donde es difícil percibir el momento en que se equivocó la ruta. Entre tanto, la base económica adaptada ha hecho su trabajo de zapa sobre el desarrollo de la conciencia. Para construir el comunismo, simultáneamente con la base material hay que hacer al hombre nuevo.

De allí que sea tan importante elegir correctamente el instrumento de movilización de las masas. Este instrumento debe ser de índole moral, fundamentalmente, sin olvidar una correcta utilización del estímulo material, sobre todo de naturaleza social.

Como ya dije, en momentos de peligro extremo es fácil potenciar los estímulos morales; para mantener su vigencia, es necesario el desarrollo de una conciencia en la que los valores adquieran categorías nuevas. La sociedad en su conjunto debe convertirse en una gigantesca escuela.

Las grandes líneas del fenómeno son similares al proceso de formación de la conciencia capitalista en su primera época. El capitalismo recurre a la fuerza, pero, además, educa a la gente en el sistema. La propaganda directa se realiza por los encargados de explicar la ineluctabilidad de un régimen de clase, ya sea de origen divino o por imposición de la naturaleza como ente mecánico. Esto aplaca a las masas que se ven oprimidas por un mal contra el cual no es posible la lucha.

A continuación viene la esperanza, y en esto se diferencia de los anteriores regímenes de casta que no daban salida posible.

Para algunos continuará vigente todavía la fórmula de casta: el premio a los obedientes consiste en el arribo, después de la muerte, a otros mundos maravillosos donde los buenos son los premiados, con lo que se sigue la vieja tradición. Para otros, la innovación; la separación en clases es fatal, pero los individuos pueden salir de aquella a que pertenecen mediante el trabajo, la iniciativa, etcétera. Este proceso, y el de autoeducación para el triunfo, deben ser profundamente hipócritas: es la demostración interesada de que una mentira es verdad.

En nuestro caso, la educación directa adquiere una importancia mucho mayor. La explicación es convincente porque es verdadera; no precisa de subterfugios. Se ejerce a través del aparato educativo del Estado en función de la cultura general, técnica e ideológica, por medio de organismos tales como el Ministerio de Educación y el aparto de divulgación del partido. La educación prende en las masas y la nueva actitud preconizada tiende a convertirse en hábito; la masa la va haciendo suya y presiona a quienes no se han educado todavía. Esta es la forma indirecta de educar a las masas, tan poderosa como aquella otra.

Pero el proceso es consciente; el individuo recibe continuamente el impacto del nuevo poder social y percibe que no está completamente adecuado a él. Bajo el influjo de la presión que supone la educación indirecta, trata de acomodarse a una situación que siente justa y cuya propia falta de desarrollo le ha impedido hacerlo hasta ahora. Se autoeduca.