Συντάκτης: Guevaristas

Σημειώσεις γιά τη μελέτη της Κουβανικής Επανάστασης

Αυτή είναι μία μοναδική επανάσταση που μερικοί άνθρωποι θεωρούν ότι αντιφάσκει με μία από τις πιο ορθόδοξες αρχές του επαναστατικού κινήματος, όπως την εξέφρασε ο Λένιν: «Χωρίς επαναστατική θεωρία, δεν υπάρχει επαναστατικό κίνημα». Μπορούμε να πούμε πως η επαναστατική θεωρία, ως έκφραση μιας κοινωνικής αλήθειας, υπερβαίνει κάθε διακήρυξή της, δηλαδή, ακόμα και αν η θεωρία δεν είναι γνωστή, η επανάσταση μπορεί να επιτύχει αν η ιστορική αλήθεια ερμηνευτεί σωστά και αν οι εμπλεκόμενες δυνάμεις χρησιμοποιηθούν με το σωστό τρόπο. Κάθε επανάσταση, πάντα συνδυάζει διαφορετικές τάσεις, οι οποίες παρόλα αυτά ταυτίζονται στην πράξη και όσον αφορά τους άμεσους στόχους της επανάστασης.

Αυτή είναι μία μοναδική επανάσταση που μερικοί άνθρωποι θεωρούν ότι αντιφάσκει με μία από τις πιο ορθόδοξες αρχές του επαναστατικού κινήματος, όπως την εξέφρασε ο Λένιν: «Χωρίς επαναστατική θεωρία, δεν υπάρχει επαναστατικό κίνημα». Μπορούμε να πούμε πως η επαναστατική θεωρία, ως έκφραση μιας κοινωνικής αλήθειας, υπερβαίνει κάθε διακήρυξή της, δηλαδή, ακόμα και αν η θεωρία δεν είναι γνωστή, η επανάσταση μπορεί να επιτύχει αν η ιστορική αλήθεια ερμηνευτεί σωστά και αν οι εμπλεκόμενες δυνάμεις χρησιμοποιηθούν με το σωστό τρόπο. Κάθε επανάσταση, πάντα συνδυάζει διαφορετικές τάσεις, οι οποίες παρόλα αυτά ταυτίζονται στην πράξη και όσον αφορά τους άμεσους στόχους της επανάστασης.

Είναι ξεκάθαρο, πως αν οι ηγέτες έχουν μία στοιχειώδη θεωρητική γνώση πριν τη δράση, μπορούν να αποφύγουν δοκιμές και σφάλματα, όταν αυτή η θεωρία ανταποκρίνεται στην πραγματικότητα. Οι κύριοι πρωταγωνιστές αυτής της επανάστασης δεν διέθεταν συνεπή θεωρητικά κριτήρια, αλλά δεν μπορούμε να πούμε πως ήταν αδαείς ως προς αρκετές παραμέτρους της ιστορίας, της κοινωνίας, της οικονομίας, και των επαναστάσεων που απασχολούν τον κόσμο σήμερα. Η βαθιά γνώση της πραγματικότητας, η στενή επαφή με το λαό, η σταθερότητα των στόχων του απελευθερωτή καθώς και η πρακτική επαναστατική εμπειρία, έδωσαν στους ηγέτες αυτούς την ευκαιρία να διαμορφώσουν ένα πιο πλήρες θεωρητικό σύστημα.

Όλα αυτά θα πρέπει να θεωρηθούν ως μία εισαγωγή στην εξήγηση αυτού του περίεργου φαινομένου που ευαισθητοποίησε όλο τον κόσμο: την Κουβανική Επανάσταση. Είναι άξιο διερεύνησης, στην σύγχρονη παγκόσμια ιστορία, πώς και γιατί μία ομάδα ανθρώπων, κατεστραμμένη από έναν ασύγκριτα ανώτερο, σε τεχνική και εξοπλισμό, στρατό κατάφερε καταρχήν να επιβιώσει, να γίνει δυνατή και αργότερα δυνατότερη από τον εχθρό στα πεδία της μάχης, να συνεχίσει κατόπιν σε νέες ζώνες μετώπου και τελικά να νικήσει τον εχθρό, αν και τα στρατεύματά της ήταν ακόμα μικρότερα σε αριθμό.

Φυσικά, εμείς που δεν δείχνουμε το απαιτούμενο ενδιαφέρον για την θεωρία, δεν διατρέχουμε τον κίνδυνο να εκθέσουμε την αλήθεια της κουβανικής επανάστασης ως να ήμασταν οι αυθεντίες της. Θα προσπαθήσουμε απλά να δώσουμε τις βάσεις για την ερμηνεία αυτής της αλήθειας. Στην πραγματικότητα, η κουβανική επανάσταση θα πρέπει να διαχωριστεί σε δύο διακριτά επίπεδα: εκείνο της ένοπλης δράσης μέχρι την 1η Ιανουαρίου 1959, και των πολιτικών, οικονομικών και κοινωνικών μεταρυθμίσεων που ακολούθησαν.

Ακόμα και αυτά τα δύο επίπεδα, πρέπει να υποδιαιρεθούν, ωστόσο δεν θα ασχολήθουμε με αυτά υπό το πρίσμα της ιστορικής έκθεσης, αλλά από την οπτική της εξέλιξης της επαναστατικής σκέψης των ηγετών τους, μέσω της επαφής τους με τον λαό. Με την ευκαιρία, εδώ πρέπει να τοποθετηθούμε γενικά απέναντι σε έναν από τους πιο αμφιλεγόμενους όρους του σύγχρονου κόσμου: τον μαρξισμό. Όταν μας ρωτούν αν είμαστε Μαρξιστές, η θέση μας είναι η ίδια με εκείνη ενός φυσικού ή βιολόγου στο ερώτημα αν είναι «με τον Νεύτωνα» ή «με τον Παστέρ» αντίστοιχα.

Υπάρχουν αλήθειες τόσο εμφανείς και μέρος της ανθρώπινης γνώσης, ώστε είναι σήμερα άσκοπο να τις συζητούμε. Πρέπει να είναι κανείς «Μαρξιστής», τόσο φυσικά όσο είναι κάποιος με τον Νεύτωνα στη φυσική ή με τον Παστέρ στη βιολογία, αναλογιζόμενος πως αν νέα δεδομένα καθορίσουν νέες αντιλήψεις, οι αντιλήψεις αυτές δεν στερούν από τις παλαιότερες το μέρος της αλήθειας που κατέχουν. Τέτοια είναι για παράδειγμα η περίπτωση της σχετικότητας του Αϊνστάιν ή της κβαντικής θεωρίας του Πλανκ, σε σχέση με τις ανακαλύψεις του Νεύτωνα. Δεν αφαιρούν τίποτα από το μεγαλείο του σοφού Άγγλου. Χάρη στο Νεύτωνα, η φυσική κατάφερε να εξελιχθεί ανακαλύπτοντας νέες έννοιες του διαστήματος. Ο σοφός Άγγλος πρόσφερε το αναγκαίο σκαλοπάτι για τους επόμενους.

Οι εξελίξεις στις κοινωνικές και πολιτικές επιστήμες, όπως και σε άλλους τομείς, αποτελούν τμήματα μίας μακράς ιστορικής πορείας, που συνδέονται μεταξύ τους, αλληλοπροστίθενται και διαρκώς οδηγούν σε βελτιώσεις. Στις αρχές της ιστορίας του ανθρώπου, υπήρξαν τα μαθηματικά των Κινέζων, των Αράβων ή των Ινδών. Σήμερα, τα μαθηματικά δεν έχουν σύνορα. Στην πορεία της ιστορίας, υπήρξε ένας Έλληνας Πυθαγόρας, ένας Ιταλός Γαλιλαίος, ένας Άγγλος Νεύτωνας, ένας Γερμανός Γκάους, ένας Ρώσος Λομπατσέφκσι, ένας Αϊνστάιν κ.λπ. Έτσι και στον τομέα των κοινωνικών και πολιτικών επιστημών, από το Δημόκριτο μέχρι τον Μαρξ, μία μακρά σειρά από στοχαστές πρόσθεσαν τις δικές τους πρωτότυπες έρευνες και διαμόρφωσαν ένα σώμα εμπειρίας και αντιλήψεων.

Η συνεισφορά του Μαρξ είναι πως ξαφνικά παρήγαγε μία ποιοτική αλλαγή στην ιστορία της κοινωνικής σκέψης. Ερμηνεύει την ιστορία, κατανοεί τη δυναμική της και προβλέπει το μέλλον (πράγμα που από μόνο του ικανοποιεί την επιστημονική του υποχρέωση), αλλά επί πρόσθετα εκφράζει μία επαναστατική αντίληψη: ο κόσμος δεν αρκεί να ερμηνευτεί αλλά θα πρέπει να μεταβληθεί. Ο άνθρωπος παύει να αποτελεί δούλο και εργαλείο του περιβάλλοντός του, μετατρέποντας τον εαυτό του σε αρχιτέκτονα της μοίρας του. Εκείνη τη στιγμή, ο Μαρξ θέτει τον εαυτό του στόχο όλων εκείνων που ενδιαφέρονται να διατηρήσουν την παλιά τάξη, όπως άλλοτε με τον Δημόκριτο του οποίου το έργο κάηκε από τον Πλάτωνα και τους ακόλουθούς του, τους ιδεολόγους της Αθηναϊκής αριστοκρατίας των δούλων. Με αφετηρία τον επαναστατικό Μαρξ, μία πολιτική ομάδα με στέρεες ιδέες εδραιώθηκε. Βασιζόμενη στος γίγαντες Μαρξ και Έγγελς, εξελίχθηκε σταδιακά χάρη σε προσωπικότητες όπως ο Λένιν, ο Στάλιν, ο Μάο Τσετούνγκ και οι νέοι ηγέτες της Σοβιετικής Ένωσης και της Κίνας, διαμόρφωσε ένα σύνολο δογμάτων και ας μας επιτραπεί να πούμε, παραδείγματα για να ακολουθήσουμε.

Η κουβανική επανάσταση παίρνει τον Μαρξ από το σημείο εκείνο στο οποίο ο ίδιος εγκατέλειψε την επιστήμη για να φέρει στον ώμο το επαναστατικό τουφέκι. Και τον πιάνει από εκείνο το σημείο, όχι με διάθεση ρεβιζιονισμού ενάντια αυτών που ακολουθούν τον Μαρξ ή αποκατάστασης ενός «καθαρού» Μαρξ, αλλά γιατί σε εκείνο το σημείο, ο επιστήμονας Μαρξ, έθετε τον εαυτό του έξω από την Ιστορία, την οποία μελετούσε και προέβλεπε. Ήταν από εκεί και πέρα που ο επαναστάτης Μαρξ μπορούσε να αγωνιστεί μέσα στην Ιστορία.

Εμείς οι πρακτικοί επαναστάτες ακολουθούμε απλώς τους νόμους που προέβλεψε ο Μαρξ, ο επιστήμονας. Προσαρμοζόμαστε στις προβλέψεις του επιστήμονα Μαρξ, καθώς διασχίζουμε τον δρόμο της εξέγερσης, αντιπαλεύοντας την παλαιά δομή εξουσίας, στηριζόμενοι στο λαό για την καταστροφή αυτής της δομής και έχοντας την ευτυχία του λαού ως βάση του αγώνα μας. Δηλαδή, και είναι καλό να το τονίσουμε μία ακόμα φορά, οι νόμοι του Μαρξισμού περιέχονται στα γεγονότα της κουβανικής επανάστασης, ανεξάρτητα από το τί γνωρίζουν οι ηγέτες της για αυτούς, από θεωρητικής πλευράς.

Πριν την απόβαση του Γκράνμα, κυριαρχούσε μία νοοτροπία, που θα μπορούσε να χαρακτηριστεί, σε ένα βαθμό «ιδεαλιστική»: τυφλή σιγουριά για μία αστραπιαία λαϊκή έκρηξη, ενθουσιασμός και πίστη στην δυνατότητα ανατροπής του καθεστώτος του Μπατίστα μέσω ενός ένοπλου ξεσηκωμού συνδυασμένου με αυθόρμητες επαναστατικές απεργίες.που θα προκαλούσαν την πτώση του δικτάτορα. […]

Μετά την απόβαση έρχεται η ήττα, η σχεδόν ολοσχερής καταστροφή των δυνάμεων και η επανασυγκρότησή τους σε αντάρτικο. Οι λιγοστοί – αποφασισμένοι για τον αγώνα – που επιβίωσαν, κατανόησαν πως το να βασίζονται σε μαζικούς ξεσηκωμούς σε όλη την έκταση του νησιού ήταν λάθος, μία ψευδαίσθηση. Κατάλαβαν επίσης πως ο αγώνας θα ήταν μακρύς και ότι απαιτούσε μεγάλη συμμετοχή των χωρικών. Εκείνη την περίοδο, οι αγρότες προσχωρούσαν στον ανταρτοπόλεμο για πρώτη φορά.

Δύο γεγονότα συνέβησαν, μικρής αξίας σε σχέση με τον αριθμό των πολεμιστών που συμμετείχαν, αλλά μεγάλης ψυχολογικής σημασίας. Καταρχήν, ο ανταγωνισμός που ένιωθαν οι άντρες των πόλεων – που αποτελούσαν την αντάρτικη ομάδα – απέναντι στους χωρικούς έσβησε. Με τη σειρά τους, οι χωρικοί ήταν επιφυλακτικοί απέναντι στην ομάδα και κυρίως φοβούνταν τα σκληρά αντίποινα της κυβέρνησης. Σε αυτή τη φάση, δύο πολύ σημαντικές διαπιστώσεις προέκυψαν: στους χωρικούς έγινε φανερό πως οι παράνομες φορολογίες του στρατού και οι διωγμοί δεν θα αρκούσαν για την λήξη του αντάρτικου, ακόμα και τη στιγμή που ο στρατός μπορούσε να εξολοθρεύσει τα σπίτια, τη συγκομιδή και τις οικογένειές τους. Συνεπώς ήταν καλή λύση να καταφύγουν στους αντάρτες. Από την πλευρά τους, οι αντάρτες έμαθαν ότι ήταν όλο και περισσότερο αναγκαίο να «κερδίσουν» τις μάζες των χωρικών. […]

[Μετά την αποτυχία της κύριας επίθεσης του Μπατίστα στον Επαναστατικό Στρατό], ο πόλεμος παίρνει νέα μορφή: η αναλογία των δυναμέων κλίνει προς το μέρος της επανάστασης. Μέσα σε ενάμισι μήνα, δύο ολιγάριθμες φάλλαγες, η πρώτη 80 και η άλλη 140 ανδρών, διαρκώς περιστοιχισμένες και διωκόμενες από έναν στρατό χιλιάδων στρατιωτών, διέσχισαν τις πεδιάδες του Camagüey, έφθασαν στη Λας Βίγιας και ξεκίνησαν το έργο του διαχωρισμού του νησιού στα δύο. Ίσως μοιάζει παράδοξο, ακατανόητο, ακόμα και εντυπωσιακό πως δύο φάλλαγες τόσο μικρού μεγέθους – χωρίς επικοινωνία, μεταφορικά μέσα, χωρίς το στοιχειώδη οπλισμό του σύγχρονου ανταρτοπολέμου – κατόρθωσαν να πολεμήσουν εναντίον καλά εκπαιδευμένων και πάνω απ’ όλα καλά εξοπλισμένων μονάδων. Βασικό στοιχείο [για τη νίκη] είναι ο χαρακτήρας της κάθε στρατιάς: όσο λιγότερες ανέσεις έχει ο αντάρτης, τόσο περισσότερο μυείται στις κακουχίες της ζωής στη φύση και αισθάνεται σαν στο σπίτι του. Το ηθικό του είναι υψηλότερο, η αίσθηση ασφάλειας είναι μεγαλύτερη. Την ίδια στιγμή, έχει μάθει να θέτει σε κίνδυνο τη ζωή του σε κάθε περίσταση, να την εμπιστεύεται στην τύχη σαν να παίζει κορώνα-γράμματα. Γενικά, σε αυτό το είδος πολέμου, ελάχιστα μετρά στον κάθε αντάρτη αν θα επιζήσει ή όχι. Ο εχθρός, στο παράδειγμα της Κούβας, είναι ο κατώτερος συνέταιρος του δικτάτορα, είναι ο άνθρωπος στον οποίο αφήνονται τα τελευταία ψίχουλα από μία μακρά αλυσίδα κερδοσκόπων, ξεκινώντας από τη Γουώλ Στρητ και καταλήγοντας σε εκείνον. Ο ρόλος του είναι να υπερασπιστεί τα προνόμιά του, αλλά μόνο μέχρι το σημείο που αυτό έχει σημασία για τον ίδιο. Ο μισθός του και η σύνταξή του αξίζουν κάποια ταλαιπωρία και κινδύνους, αλλά σε καμία περίπτωση την ίδια τη ζωή του. Αν το τίμημα για την υπεράσπισή τους είναι τέτοιο, τότε είναι καλύτερο για αυτόν να τα εγκαταλείψει, υποχωρώντας δηλαδή μπροστά στον αντάρτη. Από αυτές τις δύο διαπιστώσεις, και την ηθική τους, αναδεικνύεται η διαφορά που έμελλε να προκαλέσει την κρίση της 31ης Δεκεμβρίου 1958. […]

Εδώ παίρνει τέλος η σύγκρουση. Αλλά οι άντρες που φθάνουν στην Αβάνα μετά από δύο χρόνια αγώνα στα βουνά και τις πεδιάδες του Οριέντε, στις πεδιάδες του Camagüey και στα βουνά, τις πεδιάδες και τις πόλεις της Λας Βίγιας, δεν είναι οι ίδιοι άνθρωποι, ιδεολογικά, με αυτούς που προσάραξαν στις ακτές της Λας Κολοράντας ή με αυτούς που πήραν μέρος στην πρώτη φάση του αγώνα. Η δυσπιστία τους απέναντι στους χωρικούς έχει μεταβληθεί σε οικειότητα και σεβασμό για τις αρετές τους. Η ολοκληρωτική άγνοιά τους για την αγροτική ζωή έχει μεταβληθεί σε γνώση των αναγκών των χωρικών. Η προσήλωσή τους σε στατιστικές και θεωρίες έχει πλέον συνδεθεί με την καθημερινή πραγματικότητα.

Με σημαία την Αγροτική Μεταρρύθμιση, η πραγματοποίηση της οποίας ξεκινά στη Σιέρα Μαέστρα, αυτοί οι άντρες συγκρούονται με τον ιμπεριαλισμό. Γνωρίζουν ότι η Αγροτική Μεταρρύθμιση είναι η βάση πάνω στην οποία θα χτιστεί η νέα Κούβα. Γνωρίζουν επίσης ότι θα δώσει γη σε όλους τους μη κατέχοντες αλλά και ότι θα απογυμνώσει τους παράνομους σφετεριστές της, γνωρίζοντας ότι οι μεγαλύτεροι εκμεταλλευτές είναι άνθρωποι που ασκούν επιρροή στο Στέητ Ντιπάρτμεντ ή την κυβέρνηση των Ηνωμένων Πολιτειών της Αμερικής. Αλλά έμαθαν ήδη να νικούν τις δυσκολίες με γενναιότητα, με κουράγιο και κυρίως με την υποστήριξη του λαού. Και βλέπουν πλέον στο μέλλον την απελεύθερωση που περιμένει, πέρα από τις κακουχίες.

Ραμόν Μπενίτεζ (Ramón Benítez)

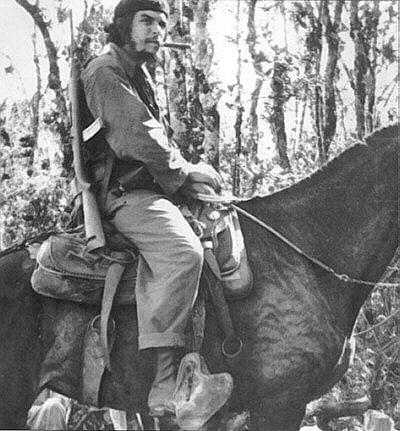

Ραμόν Μπενίτεζ ήταν το όνομα με το οποίο ο Τσε ταξίδεψε το 1966 στη Βολιβία προκειμένου να οργανώσει το εκεί αντάρτικο κίνημα. Πριν ακόμη εγκαταλείψει την Κούβα γιά τη Βολιβία – και με ελάχιστους ανθρώπους να γνωρίζουν τι επρόκειτο να συμβεί – ο Τσε μπήκε στη διαδικασία αλλαγής του παρουσιαστικού του. Έτσι, ο «Ραμόν Μπενίτεζ» ήταν ένας μεγαλύτερος ηλικιακά άνδρας (γύρω στα 55-60), με λίγα μαλλιά και χοντρά γυαλιά μυωπίας. Το παρουσιαστικό συνόδευαν και τα ανάλογα έγγραφα (διαβατήριο, σχετικές επαγγελματικές ταυτότητες) με τα οποία θα μπορούσε να περάσει ανενόχλητος τον έλεγχο του αεροδρομίου της Λα Παζ και όπου αλλού χρειαζόταν.

Πριν αναχωρήσει για τη Βολιβία ο Τσε, μεταμφιεσμένος ήδη σε Ραμόν, επισκέφτηκε γιά τελευταία φορά την οικογένεια του. Η σύζυγος του, Αλεϊδα Μαρτς, περιγράφει εκείνη την συγκινητική συνάντηση:

«Λίγες μέρες πριν από την αναχώρησή, τον μετέφεραν σε ένα ασφαλές σπίτι που βρισκόταν στην Αβάνα, μεταμορφωμένο ήδη σε γερο-Ραμόν, κι’ εκεί ζήτησε να δει τα παιδιά. Η συνάντηση έπρεπε να γίνει με αυτόν τον τρόπο, επειδή φοβόταν ότι τα μεγαλύτερα παιδιά μας, αν τον αναγνώριζαν, κάπου θα το έλεγαν, κι αυτό ίσως προκαλούσε πολύ σοβαρά προβλήματα.

Όταν έφτασαν τα παιδιά, τους τον σύστησα ως έναν στενό φίλο του μπαμπά τους απ’ την Ουρουγουάη, που ήθελε να τα γνωρίσει. Φυσικά δε φαντάστηκαν ότι εκείνος ο άντρας,

που έδειχνε εξηντάρης, μπορούσε να είναι ο πατέρας τους. Ήταν μια στιγμή πολύ δύσκολη γιά τον Τσε αλλά και για μένα. Για εκείνον βέβαια ήταν εξαιρετικά επώδυνο το να βρίσκεται τόσο κοντά τους και να μην μπορεί να τους το πει, ούτε να τους φερθεί όπως ήθελε. Ήταν μία απ’ τις πιο σκληρές δοκιμασίες που χρειάστηκε να περάσει ποτέ του. […]

Η Αλεϊδίτα, τρέχοντας ξετρελαμένη πέρα-δώθε, χτύπησε κάπου το κεφάλι της, και ήταν ο Τσε εκείνος που τη φρόντισε. Το έκανε με τόση λεπτότητα και ευαισθησία, που ύστερα από λίγο η μικρή ήρθε να μου πει ένα μυστικό, που το άκουσε κι εκείνος: «Μαμά, αυτός ο κύριος είναι

ερωτευμένος μαζί μου». Δεν είπαμε τίποτα, χλομιάσαμε μόνο σ’ όλον εκείνο το φόρτο συναισθημάτων.

Αλεϊδα Μαρτς, Αναπόληση: Η ζωή μου με τον Τσε, Εκδ. Ψυχογιός, 2007.

Ο Φιντέλ ρίχνει μια ματιά στο διαβατήριο του «Ραμόν Μπενίτεζ» ενώ ο μεταμφιεσμένος Τσε παρακολουθεί.

Ο Φιντέλ ρίχνει μια ματιά στο διαβατήριο του «Ραμόν Μπενίτεζ» ενώ ο μεταμφιεσμένος Τσε παρακολουθεί.

1. Essence of Guerrilla Warfare

1. Essence of Guerrilla Warfare It is also possible to have recourse to certain very homogeneous groups, which must have shown their efficacy previously in less dangerous tasks, in order to make use of another of the terrible arms of the guerrilla band, sabotage. It is possible to paralyze entire armies, to suspend the industrial life of a zone, leaving the inhabitants of a city without factories, without light, without water, without communications of any kind, without being able to risk travel by highway except at certain hours. If all this is achieved, the morale of the enemy falls, the morale of his combatant units weakens, and the fruit ripens for plucking at a precise moment.

It is also possible to have recourse to certain very homogeneous groups, which must have shown their efficacy previously in less dangerous tasks, in order to make use of another of the terrible arms of the guerrilla band, sabotage. It is possible to paralyze entire armies, to suspend the industrial life of a zone, leaving the inhabitants of a city without factories, without light, without water, without communications of any kind, without being able to risk travel by highway except at certain hours. If all this is achieved, the morale of the enemy falls, the morale of his combatant units weakens, and the fruit ripens for plucking at a precise moment.