Ετικέτα: Ernesto Che Guevara

Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα: Ένας επαναστάτης ενάντια στην Σοβιετική πολιτική οικονομία

Της Helen Yaffe*.

Τον Ιανουάριο του 1962 ο Γκεβάρα είπε στους συναδέλφους του στο Υπουργείο Βιομηχανιών της Κούβας (ΥΒ): «Σε καμία περίπτωση δεν λέω ότι η οικονομική αυτονομία μιας επιχείρησης με ηθικά κίνητρα, όπως διαπιστώνεται στις σοσιαλιστικές χώρες, είναι μια φόρμουλα που θα εμποδίσει την πρόοδο προς το σοσιαλισμό». Αναφερόταν στο σύστημα οικονομικής διαχείρισης που εφαρμοζόταν στο Σοβιετικό μπλοκ, γνωστό στην Κούβα, ως Σύστημα Auto-χρηματοδότησης (AFS). Μέχρι το 1966, στην κριτική του απέναντι στο Σοβιετικό Εγχειρίδιο Πολιτικής Οικονομίας, συμπεραίνει ότι η ΕΣΣΔ «επιστρέφει στον καπιταλισμό». Το κείμενο αυτό θα αποδείξει ότι η ανάλυση του Γκεβάρα εξελίχτηκε στην περίοδο μεταξύ των δύο αυτών δηλώσεων, ως αποτέλεσμα τριών ερευνητικών κατευθύνσεων: τη μελέτη της ανάλυσης του Μαρξ για το καπιταλιστικό σύστημα, την εμπλοκή σε συζητήσεις περί σοσιαλιστικής πολιτικής οικονομίας και την αναφορά στις τεχνολογικές προόδους των καπιταλιστικών επιχειρήσεων. Την ίδια εποχή ο Γκεβάρα ασχολιόταν με την πρακτική εμπειρία από την ανάπτυξη του Συστήματος Χρηματοδότησης του Προϋπολογισμού (BFS) – ένα εναλλακτικό εργαλείο για την οικονομική διαχείριση του Υπουργείου Βιομηχανίας.

Ο Γκεβάρα ήταν επικεφαλής του Τμήματος Βιομηχανοποίησης και πρόεδρος της Εθνικής Τράπεζας το 1960, όταν όλα τα χρηματοπιστωτικά ιδρύματα και το 84% της βιομηχανίας της Κούβας εθνικοποιήθηκαν. Το Σύστημα Χρηματοδότησης Προϋπολογισμού (BFS) εμφανίστηκε σαν μια πρακτική λύση στα προβλήματα που προέκυψαν από τη μετάβαση από την ιδιωτική στην κρατική ιδιοκτησία της βιομηχανικής παραγωγής. Η Κούβα είχε μια μη ισορροπημένη, στηριζόμενη στο εμπόριο οικονομία κυριαρχούμενη από ξένα συμφέροντα, κυρίως από τις Ηνωμένες Πολιτείες. Οι παραγωγικές μονάδες που πέρασαν στη δικαιοδοσία του Τμήματος εκτείνονταν από εργαστήρια τεχνιτών μέχρι εξελιγμένες μονάδες παραγωγής ενέργειας. Πολλές αντιμετώπιζαν τον κίνδυνο χρεοκοπίας ενώ άλλες ήταν πολύ κερδοφόρες. Η λύση του Γκεβάρα είχε δυο σκέλη: πρώτον, να ομαδοποιηθούν επιχειρήσεις με παραπλήσιες γραμμές παραγωγής σε κεντρικά διοικητικά όργανα που θα ονομάζονταν Ενοποιημένες Επιχειρήσεις. Αυτό επέτρεπε στο Τμήμα να ελέγχει την κατανομή του ολιγάριθμου διοικητικού και τεχνικού προσωπικού, μετά την αποχώρηση του 65-75% των μάνατζερς, τεχνικών και μηχανικών μετά το 1959 – και, δεύτερον, για να συγκεντρώσει τα οικονομικά όλων των παραγωγικών μονάδων σε έναν τραπεζικό λογαριασμό (ενιαίο ταμείο) για την πληρωμή των μισθών, για τον έλεγχο των επενδύσεων και τη διατήρηση της παραγωγής σε βασικές βιομηχανίες που δεν είχαν χρηματικούς πόρους. Με την ίδρυση του Υπουργείου Βιομηχανίας το Φλεβάρη του 1961 το Σύστημα Χρηματοδότησης Προϋπολογισμού εξελίχτηκε σε ένα συγκεντρωτικό όργανο που ενσωμάτωνε τρεις οργανωτικές δομές σε ένα μαρξιστικό θεωρητικό πλαίσιο, ώστε να προωθήσει την εκβιομηχάνιση της Κούβας, να αυξήσει την παραγωγικότητα και να θεσμοθετήσει την συλλογική διαχείριση.

Προηγμένη τεχνολογία

Ο Γκεβάρα δημιούργησε το Σύστημα Χρηματοδότησης Προϋπολογισμού με συντρόφους που κατανοούσαν τις εσωτερικές λογιστικές πρακτικές, τη διοικητική συγκεντροποίηση και την παραγωγική συγκέντρωση των αμερικάνικων επιχειρήσεων και των θυγατρικών τους στην Κούβα. Ο Γκεβάρα εξέτασε τα επίσημα έγγραφα αυτών των εταιριών καθώς περιήλθαν σε κρατικά χέρια. Ήταν εντυπωσιασμένος με τις διοικητικές τους δομές, τη χρήση κεντρικών τραπεζικών λογαριασμών και προϋπολογισμών, των συγκεκριμενοποιημένων επιπέδων ευθύνης και λήψης αποφάσεων, καθώς και των τμημάτων οργάνωσης και ελέγχου. Είπε τους συναδέλφους του ότι το Σύστημα Χρηματοδότησης Προϋπολογισμού είχε ένα λογιστικό σύστημα παρόμοιο με το σύστημα των, προ του 1959, μονοπωλίων που λειτουργούσαν στην Κούβα, με τα αποδοτικά συστήματα ελέγχου τους: «Δεν είναι σημαντικό ποιός επινόησε το σύστημα. Το λογιστικό σύστημα που εφαρμόζουν στην Σοβιετική Ένωση εφευρέθηκε επίσης επί καπιταλισμού».

Ο Γκεβάρα ταξίδεψε για πρώτη φορά στην ΕΣΣΔ το 1960. Ο βοηθός του Ορλάντο Μπορέγκο θυμάται ότι επισκέφτηκαν ένα εργοστάσιο ηλεκτρονικών που έκανε υπολογισμούς με τον άβακα. Έχοντας μελετήσει την αμερικανικής ιδιοκτησίας Ηλεκτρική Εταιρία της Κούβας, την Shell, την Texaco και άλλες επιχειρήσεις που χρησιμοποιούσαν τους τελευταίας τεχνολογίας υπολογιστές της IBM, ο Γκεβάρα έμεινε έκπληκτος από την οπισθοδρομικότητα των σοβιετικών τεχνικών. Πίστευε ότι οι πρόοδοι της ανθρωπότητας θα πρέπει να υιοθετούνται χωρίς το φόβο της ιδεολογικής μόλυνσης.

Με την επιβολή του αποκλεισμού των ΗΠΑ, η Κούβα αναγκάστηκε να αγοράσει εργοστάσια από τις σοσιαλιστικές χώρες, ιδίως της ΕΣΣΔ. Η βοήθεια αυτή ήταν απαραίτητη, όμως η σχετική παλαιότητα του εξοπλισμού συγκρούστηκε με την επιθυμία του Γκεβάρα για μετάβαση σε προηγμένη τεχνολογία. Δεν επέκρινε τους Σοβιετικούς για την καθυστέρηση αυτή καθεαυτή. Αντίθετα, παραπονέθηκε για την αντίφαση ανάμεσα στο υψηλό επίπεδο της έρευνας και ανάπτυξης στη στρατιωτική τεχνολογία και το χαμηλό επίπεδο επενδύσεων για μη-στρατιωτική παραγωγή. Έφερε αντιρρήσεις για την ιδεολογική τους αντίσταση στις σχετικές προόδους που γίνονταν στον καπιταλιστικό κόσμο. Αυτό αποτέλεσε ένα δαπανηρό λάθος από την άποψη ανάπτυξης και της διεθνούς ανταγωνιστικότητας. Για παράδειγμα: «Για καιρό η επιστήμη των συστημάτων (αυτοματοποίηση) θεωρούταν αντιδραστική επιστήμη ή ψευδο-επιστήμη … [αλλά] είναι ένας κλάδος της επιστήμης που υπάρχει και πρέπει να χρησιμοποιείται». Πρόσθεσε ότι στις ΗΠΑ η εφαρμογή της επιστήμης των συστημάτων στη βιομηχανία είχε σαν αποτέλεσμα τον αυτοματισμό – μια σημαντική παραγωγική ανάπτυξη.

Η θεμελίωση ενός συστήματος διαχείρισης βασισμένο στην καπιταλιστική τεχνολογία για την μετάβαση στο σοσιαλισμό ήταν συμβατό με τα στάδια θεωρία του Μαρξ για την ιστορία, η οποία προέβλεπε ότι ο κομμουνισμός θα αναδυόταν από τον πλήρως αναπτυγμένο καπιταλιστικό τρόπο παραγωγής. Ο Μαρξ έδειξε πως η τάση συγκέντρωσης του κεφαλαίου, δηλαδή προς το μονοπώλιο, ήταν έμφυτη στο σύστημα. Ως εκ τούτου, η μονοπωλιακή μορφή του καπιταλισμού ήταν πιο προχωρημένη από τον «τέλειο ανταγωνισμό». Το σοβιετικό σύστημα προήλθε από έναν κυρίως υπανάπτυκτο, προ-μονοπωλιακό καπιταλισμό. Ένα σοσιαλιστικό οικονομικό σύστημα διαχείρισης που θα προέκυπτε από το μονοπωλιακοό καπιταλισμό θα μπορούσε να είναι πιο προηγμένο, αποτελεσματικό και παραγωγικό. Η προέλευση του ΣΧΠ ήταν οι πολυεθνικές επιχειρήσεις της προ του 1959 Κούβας και επομένως ήταν πιο προοδευτικό από το ΑΧΣ το οποίο είχε από τον προ-μονοπωλιακό Ρωσικό καπιταλισμό.

Κριτική στο Σοβιετικό Εγχειρίδιο Πολιτικής Οικονομίας

Τον Απρίλιο του 1965, ο Γκεβάρα έφυγε από την Κούβα επικεφαλής μιας κουβανέζικης στρατιωτικής αποστολής στο Κονγκό. Οι αντάρτες ηττήθηκαν και ο Γκεβάρα έμεινε στην Τανζανία και τη Δημοκρατία τη Τσεχίας μεταξύ 1965 και 1966, όπου άρχισε την εργασία για μια ολοκληρωμένη ανάλυση της πολιτικής οικονομίας της Σοσιαλιστικής μετάβασης. Στο πλαίσιο της προετοιμασίας για το έργο αυτό, ο Γκεβάρα κράτησε σημειώσεις πάνω στο Σοβιετικό εγχειρίδιο, εφαρμόζοντας θεωρητικά επιχειρήματα του ανέπτυξε στην μεγάλη συζήτηση για το κείμενο αυτό. Οι σημειώσεις αυτές δεν γράφτηκαν προκειμένου να δημοσιευθούν, ούτε υπάρχουν ως κείμενο. Ήταν σχόλια που αντιστοιχούσαν σε συγκεκριμένες παραγράφους του Εγχειριδίου. Σημειώσεις για τον εαυτό του, συμπεριλαμβανομένων των ενδείξεων των τομέων για περαιτέρω μελέτη.

Ο Γκεβάρα επέκρινε τη μηχανιστική προσέγγιση του Εγχειριδίου πάνω στις κλασσικές μαρξιστικές αντιλήψεις για τις ταξικές σχέσεις ανάμεσα στην αστική τάξη και την εργατική τάξη, χωρίς να λαμβάνεται υπόψη η επίδραση του ιμπεριαλισμού ο οποίος δημιούργησε μια προνομιούχα εργατική τάξη στις προηγμένες καπιταλιστικές χώρες, καθώς και τους προνομιούχους τομείς (παραγωγής) στα εκμεταλλευόμενα κράτη. Απέρριψε σαν οπορτουνισμό τις προσπάθειες του Εγχειριδίου να ξεπεράσει την εγγενή βία της ταξικής πάλης στη μετάβαση από τον καπιταλισμό στο σοσιαλισμό.

Όσον αφορά την περίοδο της μετάβασης, ο Γκεβάρα υποστήριξε ότι το συλλογικό σύστημα των «κολχόζ» (συνεταιριστικών αγροκτημάτων) της ΕΣΣΔ δεν ήταν χαρακτηριστικό του σοσιαλισμού και ότι οι συνεταιρισμοί δεν ήταν μια σοσιαλιστική μορφή ιδιοκτησίας – δημιούργησαν ένα καπιταλιστικό εποικοδόμημα το οποίο συγκρούστηκε με την κρατική ιδιοκτησία και τις σοσιαλιστικές κοινωνικές σχέσεις επιβάλλοντας τη δική τους λογική πάνω στην κοινωνία. Ο Γκεβάρα αντέκρουε συστηματικά τους λεγόμενους νόμους του Σοσιαλισμού που αναφέρονται στο Εγχειρίδιο, ιδιαίτερα το νόμο της διαρκούς αύξησης της εργατικής παραγωγικότητας – το οποίο οργισμένος αποκαλούσε ότι: «Είναι η τάση που έχει οδηγεί τον καπιταλισμό για αιώνες». Καταδίκασε ως «επικίνδυνη» τη σοβιετική πολιτική της ειρηνικής συνύπαρξης και της οικονομικής άμιλλας με τις αναπτυγμένες καπιταλιστικές χώρες και επισήμαινε τις σοβαρές διαφωνίες ανάμεσα στις σοσιαλιστικές χώρες, κατηγορώντας τες για άνισες ανταλλαγές και την επιβολή των καπιταλιστικών κατηγοριών στις εμπορικές σχέσεις.

Ταυτόχρονα με τον σεβασμό, το θαυμασμό και τα επαναστατικά κίνητρα, ο Γκεβάρα ανακοίνωσε ότι ο Λένιν ήταν ο τελικός ένοχος επειδή η Νέα Οικονομική Πολιτική (ΝΕΠ), η οποία είχε αναγκαστεί να εισαγάγει το 1921 επέβαλε ένα καπιταλιστικό εποικοδόμημα στην ΕΣΣΔ. Η ΝΕΠ δεν εφαρμόστηκε ενάντια στη μικρή εμπορευματική παραγωγή, δήλωσε ο Γκεβάρα, αλλά κατ ‘απαίτηση αυτής. Η μικρή εμπορευματική παραγωγή περιέχει τα σπέρματα της καπιταλιστικής ανάπτυξης. Ήταν σίγουρος ότι ο Λένιν θα είχε αντιστρέψει (αλλάξει) τη ΝΕΠ εάν ζούσε περισσότερο. Ωστόσο, οι οπαδοί του Λένιν «δεν είδαν τον κίνδυνο κι έτσι παρέμεινε σαν ο Δούρειος Ίππος του σοσιαλισμού, το άμεσο υλικό κίνητρο ως ένας οικονομικός μοχλός». Αυτό το καπιταλιστικό εποικοδόμημα περιχαρακώθηκε, επηρεάζοντας τις παραγωγικές σχέσεις και δημιουργώντας ένα υβριδικό σύστημα σοσιαλισμού με καπιταλιστικά στοιχεία που αναπόφευκτα προκάλεσε συγκρούσεις και αντιθέσεις οι οποίες όλο και περισσότερο επιλύονταν προς όφελος του εποικοδομήματος – ο καπιταλισμός επέστρεφε στο σοβιετικό μπλοκ.

Οι σημειώσεις του Γκεβάρα προσφέρουν μια ξεκάθαρη κριτική της σοβιετικής πολιτικής οικονομίας. Ο ίδιος προειδοποίησε ότι μερικοί ενδέχετο να παρερμηνεύσουν το έργο του γιά ακραίο αντικομμουνισμό που μεταμφιέζεται ως θεωρητικό επιχείρημα, αλλά υποστήριξε ότι η αδυναμία της αστικής οικονομίας να ασκήσει κριτική στον εαυτό της, όπως ανέδειξε ο Μαρξ στην αρχή του «Κεφαλαίου», παρατηρήθηκε στον σύγχρονο μαρξισμό. Αφιέρωσε τη δουλειά του αυτή στους κουβανούς φοιτητές που περνούν από την επώδυνη διαδικασία της εκμάθησης «αιώνιων αλήθειών» στα ανατολικοευρωπαϊκά εγχειρίδια. Κατέληξε στο συμπέρασμα ότι: Η ανθρωπότητα θα αντιμετωπίσει πολλές εκπλήξεις (σοκ) μέχρι την τελική απελευθέρωση, αλλά δεν μπορούμε να φτάσουμε εκεί χωρίς ριζική αλλαγή στην στρατηγική των πρώτων σημαντικότερων σοσιαλιστικών δυνάμεων.

Συμπέρασμα

Αυτή η εργασία συνόψισε την ανάλυση που οδήγησε το Γκεβάρα να προειδοποιήσει για την κατάρρευση του Σοσιαλισμού στο σοσιαλιστικό μπλοκ. Έκανε μια σημαντική συνεισφορά τόσο στη θεωρία και την πράξη της οικοδόμησης του σοσιαλισμού. Ήλπιζε να πείσει τις σοσιαλιστικές χώρες να αντικαταστήσουν σταδιακά τους καπιταλιστικούς μηχανισμούς κατά τη διάρκεια της μετάβασης και πρόσφερε εναλλακτικές πολιτικές προς στην κατεύθυνση αυτή. Οι προειδοποιήσεις του δεν εισακούστηκαν και, για τους λόγους που ο Γκεβάρα προέβλεψε, μεταξύ άλλων, ο καπιταλισμός επανήλθε σε όλες αυτές τις χώρες. Στην Κούβα, η ανάλυση του ήταν επανεξετάστηκε στα μέσα της δεκαετίας του 1980 κατά την περίοδο της λεγόμενης Διόρθωσης (Rectification), όταν η χώρα απομακρύνθηκε από το σοβιετικό μοντέλο προτού αυτό καταρρεύσει, βοηθώντας έτσι στην επιβίωση του σοσιαλισμού στην Κούβα.

(Μετάφραση – Επιμέλεια: Νικόλαος Μόττας)

* Η Dr. Helen Yaffe είναι αρθρογράφος και ερευνήτρια Οικονομικής Θεωρίας στο Ινστιτούτο Αμερικανικών Σπουδών του University College London. Είναι η συγγραφέας του βιβλίου «Che Guevara: The Economics of Revolution» (Palgave McMilan, 2007)», απόσπασμα του οποίου είναι το παρόν κείμενο.

Che’s ideas are absolutely relevant today: A speech by Fidel Castro (Part Four)

Starting out from the idea that rectification means, as I’ve said before, looking for new solutions to old problems, rectifying many negative tendencies that had been developing; that rectification implies making more accurate use of the system which, as we said at the enterprises meeting, was a horse, a lame nag with may sores that we were treating with mercurochrome and prescribing medicines for, putting splints on one leg, in short, fixing up the nag, the horse. I said that the thing to do now was to go on using that horse, knowing its bad habits, the perils of that horse, how it kicked and bucked, and try to lead it on our path and not go wherever it wishes to take us. I’ve said, let us take up the reins!

Starting out from the idea that rectification means, as I’ve said before, looking for new solutions to old problems, rectifying many negative tendencies that had been developing; that rectification implies making more accurate use of the system which, as we said at the enterprises meeting, was a horse, a lame nag with may sores that we were treating with mercurochrome and prescribing medicines for, putting splints on one leg, in short, fixing up the nag, the horse. I said that the thing to do now was to go on using that horse, knowing its bad habits, the perils of that horse, how it kicked and bucked, and try to lead it on our path and not go wherever it wishes to take us. I’ve said, let us take up the reins!

These are very serious, complicated matters and here we can’t afford to take shots in the dark, and there’s no place for adventure of any kind. The experience of so many years that quite a few of us have had the privilege of accumulating through a revolutionary process is worth something. And that’s why we say now, we cannot continue fulfilling the plan simply in terms of monetary value! We must also fulfill it in terms of goods produced. We demand this categorically, and anyone who does otherwise must be quickly replaced, because there’s no other choice! We maintain that all projects must be started and finished quickly so that there is never a repeat of what happened to us on account of the nag’s bad habits: that business of doing the earthmoving and putting up a few foundations because that was worth a lot and then not finishing the building because that was worth little; that tendency to say, “I fulfilled my plan as to value but I didn’t finish a single building,” which made us waste hundred of millions, billions, and we never finished anything.

It took fourteen years to build a hotel. Fourteen years wasting iron bars, sand, stone, cement, rubber, fuel, manpower before the country made a single penny from the hotel being used. Eleven years to finish our hospital here in Pinar del Río! It’s true that in the end it was finished and it was finished well, but things of this sort should never happen again. The minibrigades, which were destroyed for the sake of such mechanisms, are now rising again from their ashes like a phoenix and demonstrating the significance of that mass movement the significance of that revolutionary path of solving the problems that the theoreticians, technocrats, those who do not believe in man, and who believe in two-bit capitalism had stopped and dismantled. This was how they were leading us into critical situations.In the capital, where the minibrigades emerged, it pains us to think that over fifteen years ago we had found an excellent solution to such a vital problem, and yet they were destroyed in their peak moment. And so we didn’t even have the manpower to building housing in the capital; and the problems kept piling up, tens of thousands of homes were propped up and were in danger of collapsing and killing people.

Now the minibrigades have been reborn and there are more than 20,000 minibrigades members in the capital. They’re not in the contradiction with the nag, with the Economic Management and the Planning System, simple because the factory or workplace that sends them to the construction site pays them, but the state reimburses the factory or workplace for the salary of the minibrigades member. The difference is that whereas the worker would normally work five or six hours, on the minibrigades he works ten, eleven or twelve hours doing the job of two or three men, and the enterprise saves money.

Our two-bit capitalist can’t say his enterprise is being ruined. On the contrary, he can say, “They’re helping the enterprise. I’m doing the job with thirty, forty or fifty less men and spending less on wages.” He can say, “I’m going to be profitable or at least lose less money; I’ll distribute more prizes and bonuses since wage expenditures will be cut down.” He organizes production better, he gets housing for his workers, who in turn are happier because they have new housing. He builds community projects such as special schools, polyclinics, day-care centers for the children of working women, for the family; in short, some many extremely useful things we are doing now and the state is building them without spending an additional cent in wages. That really is miraculous! We could ask the two-bit capitalists and profiteers who have blind faith in the mechanisms and categories of capitalism: Could you achieve such a miracle? Could you manage to build 20,000 housing units in the capital without spending a cent more on wages? Could you build fifty day-care centers in a year without spending a cent more on wages, when only five had been included in the five-year plan and they weren’t even built, and 19,5000 mothers were waiting to get their children a place, which never materialized.

At that rate, it would take 100 years! By then they would be dead, and fortunately so would all the technocrats, two-bit capitalists, and bureaucrats who obstruct the building of socialism. They would have died without ever seeing day-care center number 100. Workers in the capital will have their 100 day-care centers in two years, and workers all over the country will have the 300 or so they need in three years. That will bring enrollment to 70,000 or 80,000 easily, without paying out an additional cent in wages or adding workers, because at that rate with overstaffing everywhere, we would have ended up bring workers in from Jamaica, Haiti, some Caribbean island, or some other place in the world. That was where we were heading.It can be seen in the capital today that one in eight workers can be mobilized, I’m sure. This is not necessary because there would not be enough materials to give tasks to 100,000 people working Havana, each one doing the work of three. We’re seeing impressive examples of feats of work, and this achieved by mass methods, by revolutionary methods, by communist methods, combining the interests of people in need with the interests of factories and those of society as a whole.

I don’t want to become the judge of different theories, although I know what things I believe in and what things I don’t and can’t believe in. These questions are discussed frequently in the world today. And I only ask modestly, during the problem of rectification, during this process of this struggle — in which we’re going to continue as we already explained: with the old nag, while it can still walk, if it walks, and until we can cast it aside and replace it with a better horse as I think that nothing is good if it’s done in a hurry, without analysis and deep thought — What I ask for modestly at this twentieth anniversary is that Che’s economic thought be made known; that it be known here, in Latin America, in the world; in the developed capitalist world, in the Third World, and in the socialist world. Let it be known there too! In the same way that we may read many texts, of all varieties, and many manuals, Che’s economic thought should be known in the socialist camp. Let it be known! I don’t say they have to adopt it; we don’t have to get involved in that. Everyone must adopt the thought, the theory the thesis they consider most appropriate, that which best suits them, as judged by each country. I absolutely respect the right of every country to apply the method or systems it considers appropriate; I respect it completely!

I simply ask that in a cultured country, in a cultured world, in a world where ideas are discussed, Che’s economic theories should be made known I especially ask that our students of economics, of whom we have many and who read all kinds of pamphlets, manuals, theories abut capitalist categories and capitalist laws, also begin to study Che’s economic thought, so as to enrich their knowledge. It would be a sign of ignorance to believe there is only way of doing things arising from the concrete experience of a specific time and specific historical circumstances. What I ask for, what I limit myself to asking for, is a little more knowledge, consisting of knowing about other points-of-view, points-of-view as respected, as deserving and as coherent as Che’s points-of-view.

I simply ask that in a cultured country, in a cultured world, in a world where ideas are discussed, Che’s economic theories should be made known I especially ask that our students of economics, of whom we have many and who read all kinds of pamphlets, manuals, theories abut capitalist categories and capitalist laws, also begin to study Che’s economic thought, so as to enrich their knowledge. It would be a sign of ignorance to believe there is only way of doing things arising from the concrete experience of a specific time and specific historical circumstances. What I ask for, what I limit myself to asking for, is a little more knowledge, consisting of knowing about other points-of-view, points-of-view as respected, as deserving and as coherent as Che’s points-of-view.

I can’t conceive that our future economists, that our future generations will act, live and develop like another species of little animal, in the case like the mule, who has those blinders only so that he can’t see to either side; mules, furthermore, with grass and carrot dangling in front as their only motivation. No, I would like them to read, not only to intoxicate themselves with certain ideas, but also to look at other ones, analyze them, and think about them. Because if we are talking with Che and we said to him, “Look, all this has happened to us,” all those things I was talking about before, what happened to us in construction, in agriculture, in industry, what happened in the terms of goods actually produced, work quality, and all that, Che would have said, “It’s as I warned, what’s happening is exactly what I thought would happen,” because that’s simply the way it is. I want our people to be a people of ideas, of concepts. I want them to analyze those ideas, think about them, and if they want, discuss them. I consider these things to be essential.

It might be that some of Che’s ideas are closely linked to the initial stages of revolution, for example his belief that when a quota was surpassed, the wages received should not go above that received by those on the scale immediately above. What Che wanted was for the worker to study, and he associated his concept with the idea that our people who in those days had very poor education and little technical expertise should study. Today our people are much better educated, more cultured. We could discuss whether now they should earn as much as the next level or more. We could discuss questions associated with our reality of a far more educated people, a people far better prepared technically, although we must never give up the idea of constantly improving ourselves technically. But many of Che’s ideas are absolutely relevant today, ideas without which I am convinced communism cannot be built, like the idea that man should not be corrupted; that man should never be alienated; the idea that without consciousness, simply producing wealth, socialism as a superior society could not be built, and communism could never be built.

I think that many of Che’s ideas — many of his ideas! — have great relevance today. Had we known, had we learned about Che’s economic thought we’d be a hundred times more alert, including in riding the horse, and whenever the horse wanted to turn left of right, wherever it wanted to turn — although, mind you, here this was without a doubt a right-wing horse — we should have pulled it up hard and got it back on track, and whenever it refused to move, used the spurs hard. I think a rider, that is to say, an economist, that is to say, a party cadre, armed with Che’s ideas would be better equipped to lead the horse along the right track. Just being familiar with Che’s thought, just knowing his ideas would enable him to say, “I’m doing badly here, I’m doing badly there, that’s a consequence of this, that, or the other,” provided that the system and mechanisms for building socialism and communism are really being developed and improved on.

Read Part Five.

‘Che’ Guevara: A Sociological Analysis of a Life (Part One)

By Robin West*.

Whether we choose to regard Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara as the tragic Hegelian ‘world-individual’ whose passions are exploited and exhausted in the dialectic of change, or as an individual who finds the odds against him in his attempt to implement widespread ideological change, focus primarily falls on the actions of the historical Guevara in the context of voluntarism. Yet, as Bourdieu (1977) points out, passions and emotions become mere escapes into the transcendental layer of the self when the locus of agency is seen purely in terms of the subjective – and the agental determinisms of the objective world, toward which these passions are directed, is denied. Alternatively, to treat the actions of an individual as directly determined by prevailing conditions, external influences, or predetermined ‘roles’, is to exclude the reflective and agental capabilities of the knowledgeable actor. This paper focuses on significant events in Guevara’s life by aligning influential factors with contemporary theories of structure and agency.1 Following an introduction to the composition of his early years, Part One will consider Guevara’s youthful travels in Latin America and will draw mainly on the formation of his character by considering emotional responses as emergent properties of habitus. In Part Two, by examining the events of Che’s penultimate (and disastrous) escapade in post-colonial Congo, I suggest that dominant residues of the habitus may have affected his powers of judgement and agency when faced with multi-dimensional external structures.

I. The development of an egalitarian character: habitus and the experience of doxa.

Youth and the accumulation of dispositions.

Ernesto Guevara was born in 1928 into a blue-blooded line of Argentinian aristocracy. His father was of Spanish-Irish descent whilst his mother, Celia, came from a distinguished and landed lineage. Ernesto’s grandmother had been prominent socially as a liberal and iconoclast and was a significant figure in his life. Although Celia was educated in Catholicism, any leanings in this direction were tempered by the influence of her elder sister – a card-carrying communist – and she eventually emerged as a ‘socialist, anti-clerical feminist’. Prior to Guevara’s meeting with Fidel Castro, Celia was to be the major intellectual and political figure in his life. At the time of his birth, Argentina was a prosperous, fledgling democracy that aspired to join the ranks of ‘first world’ nations. By the late 1930’s the effects of the Depression had transformed it into a shadow of its former self: the economy collapsed, right-wing pressure groups were formed; the middle-class became disillusioned and eventually democracy was replaced by military rule. All this led to ideological polarisation and great cultural changes for the nation. During this time, Ernesto attended public school, giving rise to some curious paradoxes in his early life. Prior to the Depression, Argentina had been a fairly homogenous society that aimed at improving equality – hence Ernesto studied alongside pupils from destitute neighbourhoods and social elites alike. However, the economic troughs of the Thirties saw the emergence of a new working class compounded from the now redundant agricultural sector. Thus, on the one hand, Ernesto had early intellectual experience of social diversity – and, on the other, he was spatially separated by his social position as a scion of the Argentine elite: a position that gave him a cultural and self-enhancing advantage.

Through this sketch of the cultural background of Guevara, a sense of the initial factors that combined to furnish a particular socially conditioned disposition is revealed. We can see the nascent forms of the intellectual and cultural capital that will affect his sense of reflexive judgement in relation to external structures in later life. Bourdieu has defined the notion of a ‘socialised subjectivity’ as the habitus (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992:126): that is to say that it is the sum of the acquired patterns of thought, behaviour, and aestheticism that provides the initial bridge between the subject as ‘agent’ and the determinism of objective social structures. Habitus can therefore be considered as the internalised storehouse of cultural capital from which we draw according to the relevant situation, and which will reflect the social constitution of our ‘generalised’ worldview as a ‘system of cognitive and motivating structures’ (Bourdieu, 1977:76). In much the same manner in which Giddens considers structures as ‘rules and resources’ existing as memory traces and as the ‘organic basis of human knowledgeability’ (1984:377), habitus defines the normative conditions of the cultural ‘lifeworld’ that are drawn on as a pre-reflexive source in the individual’s phenomenological activity. An example can be taken from an experience in Ernesto’s early life. The street in which he lived bordered a shantytown district of dispossessed workers wherein a character known as the ‘man of dogs’ (as a legless cripple, he was pulled around on a small chariot by a brace of hounds) resided. One day the local children took to taunting and molesting him. Ernesto’s reaction was to attempt to intervene and plead with the children to stop – yet he was met with mockery not from the children, but from the cripple he had tried to defend, whose eyes were ‘filled with an ageless, irreparable class hatred’. This incident perhaps illustrates Ernesto’s disposition towards injustice embedded in his habitus and reflects the normative structures underlying bourgeois family life. It also reveals the taken-for-granted distinction, not so much between class divisions, but with regard to the fact that his actions could somehow be separated from his elite social positioning. Bourdieu points to the element of conservatism at play in the way that we pre-reflexively accept uncontested accounts of our social world (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992:73-74): hence pre-reflexive appraisals are defined as the doxic realm in which categorisations (such as class) conform to the established order (Bourdieu, 1977:164). Guevara’s position during this encounter can be considered as the doxa of the bourgeois ‘socialist’ lifeworld in the sense that the intellectualisation of egalitarianism effectively serves to reify class divisions. Consequentially, the contempt directed towards the cripple’s ‘saviour’ reveals the fact that the status of ‘enemy’ was conferred not on the attackers, but on the ‘rich child trying to defend him’.

In Guevara’s middle-class lifeworld the naturalisation of a class society presupposes any discourse on equality – the latter relying on the recognition of a heterodox account of antagonistic social positions. It is in this context that Mouzelis (1991:100) separates the paradigmatic from the syntagmatic play of exchanges in social interaction.3 That Guevara consciously acts on his own ethical standpoint in the above incident does not obscure the sociological observation that he uncritically imposes the ‘virtual’ morality of his habitus onto an ‘actual’ world built on diverse experiences. The consequence is the instigation of an interactional dualism in which his sense of agency is restricted. The clash of different lifeworlds, typically in the form of culturally instilled ethical agency versus antagonistic embedded structures, is a theme that re-occurs throughout his life. The following account of his travels in Latin America will draw on this premise through a hermeneutical interpretation of the intellectual challenges faced during this time and, by arguing that the modification of consciousness enriches the scope of habitus, explain how this period may have been instrumental in the intended, and unintended, outcomes of future actions.

My underlying argument is twofold: first, I suggest that Ernesto’s habitus emerges from this standpoint and is initially drawn upon in practice as the unreflexive enactment of internalised rule-games. Second, I consider the possibilities for atypical action that result from reflexive evaluations of situations. That these may fall beyond the scope of a priori experience does not conflict with Bourdieu’s emphasis on the durable and transposable nature of habitus (1977:95). Certainly, habitus should be considered as orienting the individual toward a predisposition for ‘particular’ forms of practical action (Burkitt, 2002:225), however, as new objective structures are encountered, then new modes of habitus arise in response to emergent realities (cf. King, 2000:428). This, of course, suggests that actors do not enter into new situations with tabula rasa minds given the anterior determinism of their ‘personal and culturally nuanced ideas and memories’ (Stones, 1996:48). However, whilst Bourdieu’s sense of habitus appears to bear a quality that transcends the objectivist-subjectivist divide, without due modification, it retains an overly deterministic character through its emphasis on culturally inherited dispositions (in the last instance). In terms of the individual qua personality, Bourdieu suggests that each individual system of dispositions should be considered merely as a structural variant of the wider group habitus and as the expression of the difference between subjective life courses both inside and outside of the group (1977:86). We will notice, however, that in stating this Bourdieu does not adequately consider the developmental role of subsequent experience that may occur beyond the scope of culturally instilled dispositions. By this I imply those experiences that may serve to substantiate a specific trait of character4 through either emotional or evaluative ratifications. Thus, and as Mouzelis (1991) elaborates, we must allow for the experiential trajectory that removes the actor from the limitations of pre-reflexive habitus in the form of the dispositional dimension of attitudes, skills and norms, that do not derive from a specific role, but from the actor’s wider experience of life vis-à-vis new situations. To understand actions it is necessary to look for the ‘situational dimension of social life’ that reveals an order of interaction between participants and their respective lifeworlds (cf. Mouzelis, 1991:198).

It is at this juncture that we must seek the phenomenological dimension of the actor that selectively (if not unconsciously) draws on, or rejects, the stock of cultural knowledge in conjunction to the experiences that are faced in unique interactions. It is then perhaps best to think of dispositional attributes as existing on a continuum that flows between the objective and subjective worlds.5 My overall aim is to highlight the conflicts that arise in this modification of habitus but, nonetheless, to stress the resilience of early formulations of belief and strategies. Therefore, in the subsequent accounts of events in Guevara’s life, I intend to illustrate the intransitive and transitive6 content of habitus rooted in both cultural conditioning and common-sense ‘relational’ understandings respectively. With reference to the unintended and intended outcomes of his actions, I am suggesting that habitus necessarily retains a sense of ontological dualism within the agent due to the co-existence of deeply embedded dispositions and the capacity for effective (or erroneous) reflexivity. In short, habitus simultaneously displays qualities of inertia and dynamism (cf. Noble and Watkins, 2003:524).7 In this sense, there is a constant tension between the generative possibilities of habitus and those restrictions emerging from attempts to synthesise the motivations inherent to diverse cultural beliefs.

The conjunctural development of habitus.

Between 1951 and 1954, Guevara travelled extensively through Latin America. With the above suggestions in mind, we can think of Ernesto’s trips in terms of both an initiation rite to the wider culture of the continent’s lifeworld and as a political epiphany that increases the scope of habitus. There are a number of interactions during this period that can be considered as revealing the relevance of habitus as either constricting or enabling – or, as Bourdieu (1984; 1993a; 1993b) sets out, disclosing the existence of cultural fields that consist of the objective relations between culturally positioned actors that enable or prevent the activation of a particular type of cultural capital. Initially he travelled, with a companion, from Chile through to Venezuela. I will focus on one instance that gave a broader vision of the ‘order of things’ and the conditions that underlay the social and political status quo that perpetuated a distinct sense of caste and inequality outside of his native Argentina.

We must take as an entry point the hybridity of socialism and an emotional interest (cf. James, 1884) in native culture that lay at the core of Ernesto’s personality: both can be attributed to the educational capital underlying bourgeois habitus, thus enabling later evaluations. Perhaps it is Guevara’s fascination for the ‘exotic’ that becomes fused with a nostalgic sense of primitive communism and fervent anti-imperialism that stands out in his account of this time. We find here the nascent interpretations of the reality of social divisions and the attribution of a ‘meaning’ to national and class struggle. As I hope to show in the final section, the effects that this modification of habitus has in subsequent situations have both intended and unintended outcomes on agental conduct in terms of reflexivity, motivation, and the prioritisation of concerns.

One episode in particular represents the overall point that I am trying to make. In his journey through Latin America, Guevara, apparently for the first time, engaged with the industrial proletariat and was immediately attracted both by their ‘difference’ and the limitations of authentic contact. Whilst in transit through Chile, the pair planned a visit to the Chuquicamata copper mine and, waiting for official permission, spent the night with a working couple who were ardent communists. Ernesto was acutely aware of the differences between himself and these individuals who had suffered at the hands of the authorities for their political beliefs. His diary entry is worth reproducing so as to catch the essence of the phenomenological conception that bridges his inner-world as habitus and the alien exterior world:

The couple, numb with cold, huddling together in the desert night, were a living symbol of the proletariat the world over. They didn’t have a single blanket to sleep under […] it was one of the coldest nights I’ve ever spent; but also one which made me feel a little closer to this strange, for me anyway, human species […]. Although by now we could barely make out the couple in the distance, the man’s singularly determined face stayed with us and we remembered his simple invitation: ‘Come, comrades, come and eat with us. I’m a vagrant too,’ which showed he basically despised our aimless travelling as parasitical. (Guevara, 1996:59-60. My emphasis.)

Here we seem to find echoes of the incident with the Argentinian cripple in the sense that Guevara bases his perceptual evaluation on the uncontested ethics of bourgeois mentality – hence he is unnerved by the critical rationality of his host. In terms of the distinction of habituses, there is a gulf between the shared understandings of either party – the middle-class adventurer who nonetheless proffers an ethical reflection of the situation falls short of the reality of the lived experience with which he is faced. This perhaps is not surprising given that each party in the interaction inhabit a field that does not allow for the mutual synthesis of dispositions. Despite the element of human ‘connectedness’ in the situation, it falters due to the collision of antagonistic cultural positions. Ernesto and his companion are culturally competent in their own field, yet they cannot ‘cash in’ their capital for their hosts are oblivious to the cultural rationale behind the desire to acquire knowledge through travelling. Guevara’s interpretation of the plight of the couple reveals an innocent ethical stance that takes in the tragedy of the moment but remains politically naïve; hence he declares that what had ‘burgeoned’ in the communist worker was merely the natural desire for a better life, ‘a protest against persistent hunger transformed into a love for this strange doctrine, whose real meaning he could never grasp’ but when translated as ‘bread for the poor’ became something that the worker could understand (ibid:60). In this sense, it is an almost poetic interpretation of a political affiliation that demeans the agency of the worker through its adherence to dispositional beliefs, but one, nonetheless, that prompts Guevara to engage in a level of reflection that will propel him towards a closer affiliation with the working class. This reflexivity is enabled via the occurrence of a unique situational dimension (cf. Mouzelis, 1991:198).

This youthful simplicity vis-à-vis the actual conditions of the proletariat and the wider political context becomes blurred with his interpretation of indigenous culture that is formed by the access to, and conditions of, his educational background. Thus habitus ensures an intellectual knowledge of the indigenous position, yet is impoverished by a lack of intimate contact with the ‘real world’ of events. Guevara was ‘fascinated by the tropics with their mulatto and black exoticism’ that was ‘so starkly different from his white, middle-class Buenos Aires’. He was enraptured by the ‘richness’ of indigenous culture and the mysteries that were buried in the ruins of Indian architecture – such cultural remnants signifying the last border of resistance against Spanish imperialism. What I intend to argue here is that Ernesto’s critical reflections on situations he encounters have a considerable outcome on his sense of agency. Through the newly acquired knowledge of social settings and positions, he is able, as Mouzelis outlines, to make sense of ‘micro-situations’ by constructing abstract typifications of the social world (1991:89). This seems to be consolidated into a new worldview (based increasingly on the idea of mutual Latin-Americanism) through the process of associating concrete perceptions with his (limited) understanding of ideological issues and ethical position. In the case of Guevara, Mouzelis seems quite right when he suggests that ‘these typifications are often erroneously perceived as actual macro-structures that subsume, control or generate micro-situations’ (ibid.), for the simplistic associations belie both the structural reality and the actual ordering of concerns of other individuals.

* Robin West is a teaching fellow at the University of Essex (U.K.).

‘Che’ Guevara: A Sociological Analysis of a Life (Part Two)

By Robin West.

The practice of ideology

Following the trip, Guevara eventually found himself in Guatemala. His distaste of foreign intervention in Latin America had increased and he made his first substantial contact with communist organisations challenging American hegemony. A politically mature Guevara rapidly emerged and in 1955 he was introduced to Castro. The following year he took part in the invasion of Cuba, integrating his increasing knowledge of Marxist literature with revolutionary guerrilla warfare tactics. Together with Castro, Guevara declared that agricultural workers were to be the new proletariat. Subsequent ideological conflicts within the communist world caused Castro and Guevara to move in different political directions concerning economic positions – although still close personally to Castro, Guevara experienced political isolation. In 1965 he decided to leave for the Congo and re-engage directly in the revolutionary struggle. The following section will attempt to describe how the events of this period can be explained from both the analysis of the actor – by referring to the enabling nature of bourgeois habitus – and the paradoxical affect on the interpretation of external structures both within the African context and those that were at play in the broader historical arena.

II. The Congo: tensions and consequences of habitus and doxa.

Emotions, structure, and practice

In 1960, the Congo gained independence from Belgium and fell under the control of a proto-nationalist government. Chaos ensued following provincial secessions, military coups and counter-revolts. The superpowers became involved and the situation developed ostensibly into a struggle between socialism and imperialism. I have argued that a sense of emotional reflexivity is emergent from, and generates, habitus. As we have seen, significant interactional situations appear to have provided the opportunity for the elaboration of character along these lines and have led to emotional motivation in the formulation of strategies. The situation in the Congo illustrates this well – with reports suggesting that Guevara was ‘profoundly’ moved by the combination of poverty, backwardness, and oppression structuring the potentiality of the situation. In what follows, I draw attention to the latent tensions between what can be considered as the dynamism of emotional reflexivity (such reflection propelled Guevara toward a dispositional passion for Marxist ‘guerrillaism’) and the transmutation of emotions into the structural character of dispositions that form emotive constraints in the field of action (cf. Lizardo, 2004:376).

The composition of Ernesto’s character, as we have analysed it, is one that retains the original import of his middle-class socialisation process. His belief premises concerning the spread of communism have been incorporated into this character through ideological elaboration and direct encounters with the proletariat. These factors have been accompanied by an early admiration for indigenous culture. Undoubtedly, Guevara’s success in Cuba would have ratified his ideological position and produced an unquestioning faith in his own policies. It is this habitual package that Ernesto carries with him to the Congo without adequate knowledge of the wider social forces with which he must contend for control of the situation. The event we are concerned with takes place in the field of ‘revolutionary struggle’ in which a network of actors and collectivities ‘share a certain number of fundamental interests’ (Bourdieu, 1993b:73). We must think of this network in terms of ‘position-practices’ which, from a structural perspective, sees the actors set in an institutionalised framework of relations: in this case the military/political organisation (cf. Cohen, 1989:208). Occupying the field at one level, we have the government forces opposed to the revolt – we can align this aspect with the wider historical ideological conflict through the support of the U.S. who feared a ‘communist Africa’. I will not discuss this aspect of the field further, but will concentrate on the ‘position-practices’ of Guevara and his ‘allies’. Cohen suggests that position practices must be understood by analysing the actors’ varying claims to legitimate identity in the field and the 7

practices through which claims to prerogatives are foregrounded. These then interplay with the contingent situations and often erroneous strategies that contest the performance of institutionalised reciprocities (and that can produce a struggle for control of the situation). As Cohen makes clear, the motivation behind ‘strategic forbearance’ from acting must also be considered (1989:210). It would be fair to say that revolt in the Congo failed predominantly due to the international context – however, having established our picture of Guevara’s dispositional traits as modified on a continuum, that is as emergent from the cultural background and subsequently modified through cognitive and emotional encounters, it will be useful to analyse their effect on the relational field in which he became embedded.

I want to argue that, for Guevara, Marxist and guerrilla ideology, merged with his perception of indigenous culture as primitive communism, form an internal structure that comes close to the status of ‘personal’ doxa. In this sense, the invigorating dualism between habitus and the capacity for renewed reflexive modification seems to have fallen into stagnation. Guevara had adopted an unquestioning perspective that championed the advent of the ‘New Man’ orientated by moral motivation and constructed on a new base that rose above material incentives. As Bourdieu states, ‘in each of us […] there is a part of yesterday’s man’ (1977:79) – the events of Guevara’s life had culminated in his belief that he was the agent that would produce this phenomenon through the ideological guidance of the agricultural proletariat. It is clear that world events played the key role in preventing the emergence of the ‘New Man’ in the Congo. However, the failings of Guevara can be tentatively explained in part through the cognitive implications of habitus. Stones (2001) points out that agents draw on significatory structures that condition action alongside knowledge of the situation arising from ‘practical consciousness’. Such significatory structures ‘can in no sense be direct representations’ of the exterior world. Guevara’s perspective of the world is in part constituted by the ‘imagined symbolism’ of indigenous collectivity and moral universalism that have been accepted and stored in habitus as emotional residues. However, as shall be seen, the world is perceived from multiple ideological and traditional perspectives and the actual chance of homogeneity within any situation becomes slim (Stones, 2001:186).

The dialectic of control

That Guevara did not meet with success in the Congo can be attributed to the combination of emergent structural and personal properties that are set in the wider historical framework (see Archer, 1995, 2000), that is the international political field and the more immediate field of interaction. Guevara bemoaned the motivation and discipline of the Congolese troops he commanded. The latter refused to carry supplies, ran away at the first sign of conflict and were, more-than-often, drunk. Guevara responded by drawing on his stock of knowledge of guerrilla warfare and imposed harsh disciplinary measures. More worryingly, the Africans relied heavily on dawa, a magical incantation delivered by sorcerers, to protect them in the field of battle. Guevara became concerned that any defeats would be attributed to the Cubans’ lack of faith in this respect. He also attempted to ridicule the Congolese into discipline by suggesting that they should be made to wear skirts and carry vegetables in a basket – an insult that would have mortified Hispanic mentality, but was met with hysterical laughter from the Congolese. In each of these situations Guevara fails to assimilate his dispositional strategy with the normative structures prevailing in the Congo and thus underestimates the potential power bases that may oppose attempts to establish order. Just as events in his early life failed to appreciate the actuality of situations by applying an idealisation of the overall situation (i.e. the cripple and the mine-workers), so his willingness to believe that his romanticised indigenous fighters would embrace his strategy is challenged. Consequentially, the increasing restoration of dawa and the general lack of deference can be seen as the struggle for power that emerges from the clash between the combined emotional and ideological motivation of Guevara and the doxic institutionalised ritual of the Congolese. As we shall discuss in the next section, this results in a dialectic of control (Giddens, 1984:16; 288, Stones, 1996:93) that allows the Congolese to reassert their sense of autonomy.

Giddens (1984) argues that social relations must be examined through the analysis of how individuals draw upon structural properties in their strategic conduct. Hence, contextual boundaries (in our case, the delineation of traditional practices and guerrilla tactics) are revealed by giving attention to the expression of both discursive and practical consciousness (Giddens, 1984:288). ‘Less powerful’ agents possess and perform a knowledgeability of the social situation and manage the resources that are available to them in a way that enables them to exert control over authoritative figures (ibid:373). Thus, a ‘dialectic of control’ is established that affects the ‘balance of power’ and can lead ultimately to the loss of one of the party’s agency (Stones, 1996:93-94). The situation in the Congo reached such a height that Guevara was forced to concede to the traditional practices he had idealised and abandoned any hope of effective control. This confrontational interaction must be defined in the synthesis of relevant contexts – that is Guevara’s rigid doxic appraisal of the situation as was covered above, the dispositional behaviour of the Congolese, and finally the abstract agency emerging from the historical circumstances.

Historical contexts

To explain how this dialectic of control is substantiated in the overall context we must briefly look at the prevailing conditions in the Congo, conditions that I feel were partially concealed by the myopic reflexivity resulting from Guevara’s romantic idealism and emotionally driven cognition. Whereas Guevara seemed to rely on national unity as a precondition of universal socialism, in effect ethnic division split the country – with any form of nationalism only present as a ‘vague ideological cohesion’ (Davidson, 1981). The actual rising against neo-imperialism could not truly be seen as such as it was the re-activated residue of much older tribal conflicts and intentions (ibid.).9 Any modernising ideology had always come in the guise of colonial repression, therefore the attempt to create a new social structure in a ‘liberated’ Congo was counteracted by a reversion to traditionalism, hence the dogmatic adherence to dawa. Guevara’s sentimental idealisation of indigenous culture as revolutionary vanguard seems at odds with the social reality, in this case as the Congolese recruits, without substantive political guidance, were susceptible to the structural authority of traditional magic.

Guevara, a key agent in the conflict, relates to this structure at the level of the combination of his passionate beliefs and established rules, thus acting on the basis of a synthesis of his position, disposition, and subsequent interaction in the paradigmatic sense outlined above. Conversely, the Congolese relate to socialist strategy in the context of their particular relevant position (i.e. the desire to escape any form of imperialism). The levels of knowledge to which they have access alienate them from an intimate understanding of the guerrilla rulebook by which Guevara abides. Although he has tacit knowledge of the surface rules that underpin Congolese culture, due to the overwhelming historical context and the limited knowledge of the reality of that culture (which becomes idealised in accordance to the emotional element of his habitus), Guevara has little purchase in effecting any impact in the specific time-space situation (cf. Mouzelis, 1991:100) and is thus unable to effect widespread social change. Consequentially, Guevara and the Cubans were forced to flee in defeat after seven months of frustration. Doubtless many factors beyond the influence of Guevara’s habitually conditioned judgement will have been at play in this situation. The trajectory of his habitus – negotiated though instances of determinism and emergence – almost undoubtedly gave rise to the Guevara that sought to bring socialism to the Congo. However, the values that accompanied him, as Bourdieu (1984:466) suggests, can tentatively be considered as transmuted into ‘automatic gestures’. With this I contend that despite the possibility for generative reflexivity in the face of novel situations, there is an intransient element to Guevara’s character through which rational judgement emerges in a filtered form – that is to suggest that subjective conditions for action are always constrained by the accumulated residues of experience that are ratified and embodied by the ‘emotional’ habitus (cf. Burkitt, 2002:232).

Conclusion

In this paper I have attempted to show the intransient cultural and social roots that give rise to the habitus of Che Guevara. I have sought to show that these dispositional traits are modified through a phenomenological dialogue with external conditions and are influenced by both rational and emotional reflexivity. By suggesting that these two elements reveal a dualistic nature to the agent that, nonetheless, results in a dominant course of action depending on their subjective predominance, I have attempted to illustrate Guevara’s characteristic self-assurance in his ideological standpoint that dictates the almost doxic avoidance of historical reality. This culminates in the Congolese fiasco. It is perhaps the additional dualism between Guevara’s position and traditional and international structures that provokes his final critical reflection of the situation, and, retaining some degree of agency, flees. Less than eighteen months later, having renounced Cuban nationality and whilst attempting to create ‘twenty new Vietnams’ in Latin America, Guevara was betrayed, captured, and later executed by Bolivian government forces.

Notes

1 In this paper, the narrative of the life of Guevara is taken from Jorge Castañeda’s (1997) biography Compañero. All unreferenced quotations are taken from this work. Quotations and accounts drawn from the diaries of Guevara himself are fully referenced.

2 Cultural capital, for Bourdieu, is the sum of socially transmitted ‘techniques’ that enable the subject to act competently in relevant situations (Bourdieu, 1977:89).

3.As I understand Mouzelis, the paradigmatic refers generally to the enactment of rules in a virtual unreflexive manner in which they are both the medium and the outcome of social action – thus it seems that the actor can be awarded a significant account of agency throughout interaction. The syntagmatic allows for a more relational situation in which a subject’s agency is restricted by the knowledge and agency of other participants (Mouzelis, 1991:99-100).

4. Although Bourdieu would most likely abstain from associating habitus to ‘character’, I am in sympathy with Burkitt’s attempt to root habitus in the idea of a generalised disposition that ‘suffuses’ action throughout life and thus is interpreted as a mould of the personality – or, ‘character’ (Burkitt, 2002:220).

5. By this I mean that we must consider habitus as the constantly modified result of the negotiation of phenomenological experience, memory traces, and doxa.

6 In this formulation of habitus, I draw on Lau’s (2004) account that attempts a critical realist development of Bourdieu’s theory. The intransitive nature of habitus (in my account) refers to the pre-reflexive – and therefore not directly accessible – element that is encountered only as the locus of corporeal memory (in Bourdieu’s sense of the bodily hexis (1977:82)). For Lau, habitus is considered as a ‘practical sense emergent’ from experience and thus escapes suggestions of purely cultural reductionism. However, my argument attempts to place the onus of responsibility for action on the agent’s successful negotiation of cultural conditioning and the capacity for the innovative rationalisation of situations.

7. Lizardo (2004:394), however, contends that habitus should be regarded in terms of a ‘duality of structures’ (i.e. historical and developmental) that intersect and overlap.

8. Castañeda suggests that the great tragedy of Guevara’s life was the fact that he constantly generalised the overall situation. Guevara’s hope for a unified Latin-Americanism is based on his admiration for the indigenous peasant – hence at one stage he claims that he would ‘rather be an illiterate Indian than an American millionaire’. His misconception of the situation blinds him to the fact that in reality, most Indian peasants would rather be American millionaires.

9. As Davidson tells us in his history of the Congo conflict, ‘volunteers might receive a revolutionary teaching; but with them, and more powerful, came also the beliefs of their own rural culture. Theirs, increasingly, was a messianic fiction of a golden age when the ancestors should govern once more, the goods of the Europeans should pass automatically to the Africans, and power would once again reside in spiritual shrines’ these therefore took precedence over ideas of ‘capitalism, exploitation, class conflict and the rest’ (1981: 111).

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to Rob Stones for inspiration and initial comments on an early draft of this paper. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewer for pointing out clear ambiguities and tensions in the original submission.

Bibliography

Archer, M. (1995) Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach, Cambridge: CUP.

Archer, M. (2000) Being Human: The Problem of Agency, Cambridge: CUP.

Bourdieu, P and Wacquant, L. (1992) An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, Cambridge: Polity.

Bourdieu, P. (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge: CUP.

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1993a) The Field of Cultural Production, Cambridge: Polity.

Bourdieu, P. (1993b) Sociology in Question, London: Sage.

Burkitt, I. (2002) ‘Technologies of the Self: Habitus and Capacities’ Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 32(2): 219-237.

Castañeda, J. (1997) Compañero: The Life and Death of Che Guevara, London: Bloomsbury.

Cohen, I. (1989) Structuration Theory: Anthony Giddens and the Constitution of Social Life, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Davidson, B. (1981) The People’s Cause: A History of Guerrillas in Africa,

Harlow: Longman.

Giddens, A. (1984) The Constitution of Society, Cambridge: Polity.

Guevara, E. (1996) The Motorcycle Diaries, London: Fourth Estate.

Guevara, E. (2000) The African Dream: The Diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo, London: Harvill.

James, W. (1884) ‘What is an emotion?’ Mind No. 9: 188-205.

King, A. (2000) ‘Thinking with Bourdieu against Bourdieu: A ‘Practical’ Critique of the Habitus’ Sociological Theory 18(3): 417-433.

Lau, R. (2004) ‘Habitus and the Practical Logic of Practice: An Interpretation’ Sociology 38(2): 369-387.

Lizardo, O. (2004) ‘The Cognitive Origins of Bourdieu’s Habitus’ Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 34(4):375-401.

Mouzelis, N. (1991) Back to Sociological Theory: the Construction of Social Orders, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Noble, G. and Watkins, M. (2003) ‘So, how did Bourdieu learn to play tennis? Habitus, Consciousness and Habituation’ Cultural Studies 17(3/4): 520-538.

Stones, R. (1996) Sociological Reasoning: Towards a Past-Modern Sociology, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Stones, R. (2001) ‘Refusing the Realism-Structuration Divide’, European Journal of Social Theory, Vol. 4 (2): 177-179.

Che’s ideas are absolutely relevant today: A speech by Fidel Castro (Part Three)

For example, voluntary work, the brainchild of Che and one of the best things he left us during his stay in our country and his part in the revolution, was steadily on the decline. It became a formality almost. It would be done on the occasion of a special date, a Sunday. People would sometimes run around and do things in a disorganized way. The bureaucrat’s view, the technocrat’s view that voluntary work was neither basic nor essential gained more and more ground. The idea was that voluntary work was kind of silly, a waste of time, that problems had to be solved with overtime, and with more and more overtime, and this while the regular work-day was not even being used efficiently. We had fallen into a whole host of habits that Che would have been really appalled at.

For example, voluntary work, the brainchild of Che and one of the best things he left us during his stay in our country and his part in the revolution, was steadily on the decline. It became a formality almost. It would be done on the occasion of a special date, a Sunday. People would sometimes run around and do things in a disorganized way. The bureaucrat’s view, the technocrat’s view that voluntary work was neither basic nor essential gained more and more ground. The idea was that voluntary work was kind of silly, a waste of time, that problems had to be solved with overtime, and with more and more overtime, and this while the regular work-day was not even being used efficiently. We had fallen into a whole host of habits that Che would have been really appalled at.

If Che had ever been told that one day, under the Cuban revolution, there would be enterprises prepared to steal to pretend they were profitable, Che would have been appalled. Or if he’d been told of enterprises that wanted to be profitable and give out prizes and I don’t know what else, bonuses, and they’d sell the materials allotted to them to build and charge as they had built whatever it was, Che would have been appalled.

And I’ll tell you that this happened in the fifteen municipalities in the capital of the republic, in the fifteen enterprises responsible for house repair; and that’s only one example. They’d appear as though what they’d produced was with 8,000 pesos a year, and when the chaos was done away with, it turned out they were producing 4,000 pesos worth or less. So they were not profitable. They were only profitable when they stole. Che would have been appalled if he’d been told that enterprises existed that would cheat to fulfill and even surpass their production plan by pretending to have done January’s work in December.Che would have been appalled if he’d been told that there were enterprises that fulfilled their production plan and then distributed prizes for having fulfilled it in monetary value but not in goods produced, and that engaged in producing items that meant more monetary value and refrained from producing others that yielded less profit, despite the fact that one item without the other was not worth anything.

Che would have been appalled if he’d been told that product norms were so slack, so weak, so immoral that on certain occasions almost all the workers fulfilled them two or three times over. Che would have been appalled if he’d been told that money was becoming man’s concerns, man’s fundamental motivation. He who warned us so much against that would have been appalled. Work shifts were being shortened and millions of hours of overtime reported; the mentality of our worker was being corrupted and men were increasingly being motivated by the pesos on their minds.

Che would have been appalled for he knew that communism could never be attained by wandering down those beaten capitalist paths and to follow along those paths would mean eventually to forget all ideals of solidarity and even internationalism. To follow those paths would never develop a new man and a new society. Che would have been appalled if he’d been told that a day would come when bonuses and more bonuses of all kinds would be paid, without these having anything to do with production. Were he to have a group of enterprises teeming two-bit capitalists — as we call them — playing at capitalism, beginning to think and act like capitalists, forgetting about the country, the people and high standards (because high standards just didn’t matter; all they cared about was the money being earned thanks to the low norms), he would have been appalled.

And were he to have seen that one day they would not just take manual work subject to [quantitative] productions norms — with a certain logic to it, like cutting cane doing many other manual and physical activities — but even intellectual work, even radio and television work, and the here even a surgeons’ work was likely to be subject to norms — putting just anybody under the knife in order to double or triple his income — I can truthfully say that Che would have been appalled, because none of those paths will ever lead use to communism. On the contrary, those paths lead to all the bad habits and the alienation of capitalism.

Those paths, I repeat — and Che knew it very well — would never lead us to building real socialism, as a first and transitional stage to communism. But I don’t think Che was that naïve, an idealist, or someone out of touch with reality. Che understood and took reality into consideration. But Che believed in man. And if we don’t believe in man, if we think that man is an incorrigible little animal, capable of advancing only if you feed him grass or tempt him with a carrot or whip him with a stick — anybody who believes this, anybody convinced of this will never be a revolutionary; anybody who believes this, anybody convinced of this will never be a socialist; anybody who believes this, anybody convinced of this will never be a communist. Our revolution is an example of what faith in man means because our revolution started from scratch, from nothing. We did not have a single weapon, we did not have a penny, even the men who started the struggle were unknown, and yet we confronted all that might, we confronted their hundreds of millions of pesos, we confronted the thousands of soldiers, and the revolution triumphed because we believed in man. Not only was victory made possible, but so was confronting the empire and getting this far only a short way off from celebrating the twenty-ninth anniversary of the triumph of the revolution. How could we have done all of this if we had not had faith in man?

Che had great faith in man. Che was a realist and did not reject material incentives. He deemed them necessary during the transitional stage, while building socialism. But Che attached more importance — more and more importance — to the conscious factor, to the moral factor. At the same time, it would be a caricature to believe that Che was unrealistic and unfamiliar with the reality of a society and a people who had just emerged from capitalism. But Che was mostly known as man of action, a soldier, a leader, a military man, a guerrilla, an exemplary person who always was the first in everything; a man who never asked others to do something that he himself would not do first; a model of a righteous, honest, pure, courageous man. These are the virtues he possessed and the ones we remember him by. Che was a man of very profound thought, and he had the exceptional opportunity during the first years of the revolution to delve deeply into very important aspects of the building of socialism because given his qualities, whenever a man was needed to do an important job, Che was always first there. He really was a many-sided man and whatever his assignment, he fulfilled it in a completely serious and responsible manner.

He was in INRA [National Institute of Agrarian Reform] ad managed a few industries under its jurisdiction at a time when the main industries had not yet been nationalized and only a few factories had been take over. He headed the National Bank, another of the responsibilities entrusted to him, and he also headed the Ministry of Industry when this agency was set up. Nearly all the factories had been nationalized by then and everything had to organized, production had to be maintained, and Che took on the job, as he had taken on many others. He did so with total devotion, working day and night, Saturdays and Sundays, and he really set out to solve far-reaching problems. It was then that he tackled the task of applying Marxist-Leninist principles to the organization of production, the way he understood it, the way he saw it.

He spent years doing that; he spoke a lot, wrote a lot on all those subjects, and he  really managed to develop a rather elaborate and very profound theory on the manner in which, in his opinion, socialism would be built leading to a communist society.

really managed to develop a rather elaborate and very profound theory on the manner in which, in his opinion, socialism would be built leading to a communist society.

Recently all these ideas were compiled, and an economist wrote a book that was awarded a Casa de las Américas prize. The author compiled, studied, and presented in a book the essence of Che’s economic ideas, retrieved from many of his speeches and writings — articles and speeches dealing with a subject so decisive in the building of socialism. The name of the book is The Economic Thoughts of Ernesto Che Guevara. So much has been done to recall his other qualities that this aspect, I think, has been largely ignored in our country. Che held truly profound, courageous, bold ideas, which were different from many paths already taken.

In essence — in essence! — Che was radically opposed to using and developing capitalist economic laws and categories in building socialism, he advocated something that I had often insisted on: Building socialism and communism is not just a matter producing and distributing wealth but is also a matter of education and consciousness. He was firmly opposed to using these categories, which have been transferred from capitalism to socialism, as instruments to build the new society. At a given moment some of Che’s ideas were incorrectly interpreted and, what’s more, incorrectly applied. Certainly no serious attempt was ever made to put them into practice, and there came a time when ideas diametrically opposed to Che’s economic thought began to take over.

This is not the occasion for going deeper and deeper into the subject. I’m essentially interested in expressing one idea: Today, on the twentieth anniversary of Che’s death; today, in the midst of the profound rectification process we are all involved in, we fully understand that rectification does not mean extremism, that rectification cannot mean idealism, that rectification cannot imply for any reason whatsoever a lack realism, that rectification cannot even imply abrupt changes.

Read Part Four.

Τσε Γκεβάρα: Ο άνθρωπος πίσω απ’ το μύθο

Του Νικολάου Μόττα.

Του Νικολάου Μόττα.

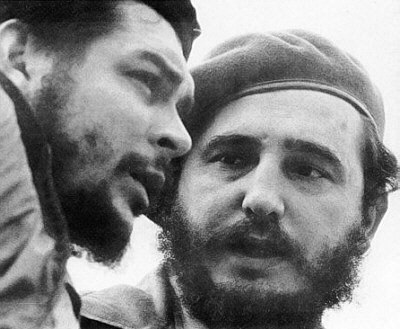

Ήταν 5 Μαρτίου 1960 όταν ο φωτογραφικός φακός του Αλμπέρτο Κόρντα αποτύπωνε τη μορφή του Ερνέστο Τσε Γκεβάρα που έμελλε να μείνει στην αιωνιότητα. Έκτοτε, εκείνη η φωτογραφία αποτέλεσε για ολόκληρες γενιές το «εικόνισμα» του ασυμβίβαστου επαναστάτη. Πέρα όμως από το βλοσυρό και αποφασιστικό βλέμμα του γενειοφόρου αργεντίνου υπήρχε και ένας άλλος Ερνέστο. Αυτός της ευρυμάθειας και της ευαισθησίας. Πέρα απ’ τον commandante υπήρχαν και άλλες, περισσότερο ανθρώπινες, όψεις του Τσε: αυτή του πολιτικού στοχαστή, αλλά και του ποιητή, του φωτογράφου, του συζύγου και πατέρα.

Μέσα από την ενδελεχή μελέτη των λόγων και των γραπτών του Γκεβάρα προκύπτει μια αξιοσημείωτη ευρεία πολιτική και κοινωνική μόρφωση εξίσου σημαντική με τις στρατηγικές του ικανότητες στον ανταρτοπόλεμο. Αφοσιωμένος μαρξιστής και ταυτόχρονα λάτρης μιας πλειάδας πνευματικών έργων που εκτείνονται από τους αρχαίους έλληνες φιλοσόφους μέχρι την πολιτική κληρονομιά του Χοσέ Μαρτί και από την ποίηση του Πάμπλο Νερούδα μέχρι τις υπαρξιακές αναζητήσεις του Ζαν Πωλ Σαρτρ. O ασπασμός της μαρξιστικής ιδεολογίας από τον Γκεβάρα δεν ήταν αποτέλεσμα αποκλειστικά και μόνο της συνεχούς διεύρυνσης των κοινωνικών ανισοτήτων και του ιμπεριαλισμού που ο ίδιος, ως φοιτητής ιατρικής, είχε αντιληφθεί ταξιδεύοντας σε χώρες της λατινικής Αμερικής. Υπήρξε και απότοκος βαθύτερης σκέψης και προσωπικών αναζητήσεων, με στόχο την κατανόηση της επανάστασης ως μέσου για την κατάκτηση της σοσιαλιστικής κοινωνίας.

Χαρακτηριστικά τα όσα γράφει στο βιβλίο της «Αναπόληση: η ζωή μου με τον Che» η σύζυγος του αργεντίνου επαναστάτη Αλέϊδα Μαρτς: «Όλοι τον γνώριζαν για τα στρατηγικά του χαρίσματα, αλλά σχεδόν τίποτα δεν ήταν γνωστό για την ευρεία θεωρητική του κατάρτιση, για την καλλιέργεια του ήδη απ’ τα χρόνια της εφηβείας του». Εκτός λοιπόν από δεινός μαχητής στα βουνά της Σιέρρα Μαέστρα, στη ζούγκλα του Κονγκό και στη βολιβιανή ύπαιθρο, ο Τσε ήταν ένας ακούραστος αναγνώστης. Ακόμη και υπό τις πλέον δύσκολες συνθήκες. Θυμάται η Αλέϊδα Μάρτς: «Διάβαζε πολύ, όπως πάντα, αλλά τώρα (σ.σ. κατά τη διάρκεια του πολέμου στο Κονγκό) το ενδιαφέρον του στρεφόταν σε ακόμη περισσότερα αντικείμενα και η μελέτη του ήταν πιο βαθιά. Είναι απίστευτο πως εν μέσω τόσων δυσκολιών, σ’έναν αφιλόξενο τόπο και έχοντας πλήρη συνείδηση για το τι τον περίμενε, εξακολουθούσε να διαβάζει φιλοσοφία και διάφορα άλλα αναγνώσματα, που θα τον βοηθούσαν να αναπτύξει θεωρίες, ικανές να ενισχύσουν το μέλλον του σοσιαλισμού στον Τρίτο Κόσμο».

Ανάμεσα στα βιβλία που ζητούσε να έχει μαζί του ήταν μεταξύ άλλων: οι Τραγωδίες του Αισχύλου, Δράματα και Τραγωδίες του Σοφοκλή, Ιστορία του Ηροδότου, τα Ελληνικά του Ξενοφώντα, οι Διάλογοι και η Πολιτεία του Πλάτωνα, τα Πολιτικά του Αριστοτέλη, ο Δον Κιχώτης, ο Φάουστ του Γκαίτε, τα Άπαντα του Σαίξπηρ. Για τον Γκεβάρα, στον κόσμο του ανταρτοπόλεμου και της πάλης ενάντια στον ιμπεριαλισμό, υπήρχε χώρος και χρόνος για την ανάγνωση αρχαίας ελληνικής φιλοσοφίας, πολιτικών δοκιμίων και ποίησης. Άλλωστε, χωρίς τη γνώση, η δημιουργία του «νέου ανθρώπου» που οραματίστηκε ο Τσε – ενός ανθρώπου απαλλαγμένου από τον εγωκεντρισμό της καπιταλιστικής κοινωνίας – θα ήταν αδύνατο να γίνει πραγματικότητα.